“An Unseen Light”: On the History of Black Memphis

*This is the introduction to our online forum on Aram Goudsouzian and Charles McKinney’s An Unseen Light

Richard Wright had to leave Memphis. Jim Crow was a cruel riddle, asking terrible questions with no good answers. By 1927, he had spent his nineteen years on earth in a long wandering loop through the South, conducting a futile search for a better life. The system of white supremacy dictated that African Americans lived behind masks, hiding their frustrations and aspirations.

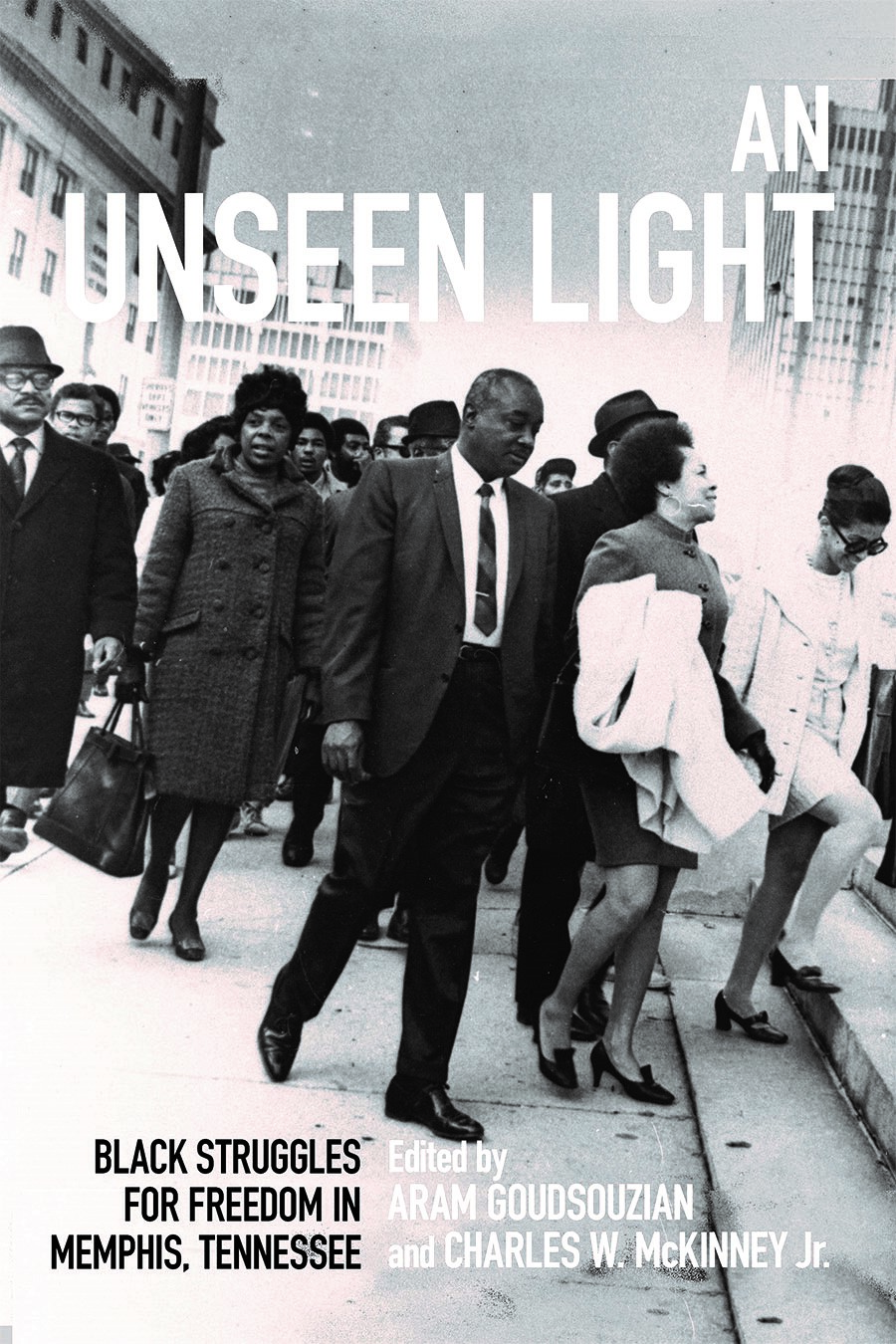

His escape came through books. He read H.L. Mencken, and Theodore Dreiser, and Sinclair Lewis, and though these whites described alien worlds, they seemed to yearn for a better America. So Wright boarded a train for Chicago, with those novels and essays serving as an inspiration, “like a tinge of warmth from an unseen light.”

We took that quote from Wright’s memoir, Black Boy, but asked a different question: what lights did Wright fail to see in Memphis? After all, African Americans shaped the politics and culture of this city at the crossroads, sitting atop a Mississippi River bluff, with the fertile and oppressive Delta fanning to its south. They fashioned resilience in its churches, courage in its political organizing, genius in its music. Over the course of the twentieth century, they forged a brilliant, complicated, dynamic movement for freedom. And they produced compelling stories, as individuals and as a people.

In An Unseen Light: Black Struggles for Freedom in Memphis, Tennessee, we sought to collect some of those stories, as told by both established and up-and-coming scholars. We believed that we were addressing a large void in southern history. Memphis remains one of the most under-researched (or “unseen”) major cities in the United States. It was the headquarters of the Church of God in Christ, the largest Black evangelical denomination in the country. Its economic vitality was anchored by Black-owned businesses and insurance companies. Black activists cultivated one of the nation’s largest and most active NAACP chapters. Beale Street was an iconic center of Black culture.

When we arrived in Memphis at our respective institutions during the 2004-2005 academic year, neither of us had any particular expertise in this region. But we both found ourselves fascinated by the city’s politics and culture. Perhaps more important, we were learning from our colleagues and mentoring students who were learning about the city’s critical place in African American history. The idea for this book developed over a dinner conversation in 2011, but the process began in earnest a few years later, as we knew that Memphis would be receiving much popular and critical attention in 2018, the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King.

In assembling this collection, we had the luxury of an extensive network of Memphis scholars. We are grateful that Zandria Robinson, Elizabeth Gritter, Laurie Green, and Michael Honey – authors of key books on Black culture and politics in Memphis – signed on. Most of the other authors had connections to our institutions. The essay authors include two University of Memphis professors and three from Rhodes College, as well as one former Rhodes professor. Four PhDs and one MA student from the U of M contributed essays. Two other authors completed their undergraduate degrees at Rhodes, then went on to earn PhDs in History. This book was built, essentially, on the foundation of our local academic community.

For this forum in Black Perspectives, we highlight five of the essays in the collection that speak to the central theme of the book – that the history of Black life and struggle in Memphis hosts a multitude of “unseen lights.” These unseen lights represent many of the core thematic elements of the Black freedom struggle: Black responses to the pervasive nature of white violence; the dynamic interior life of African Americans; the power of cultural politics; the centrality of Black women in the struggle for freedom; and the enduring role and impact of surveillance on the Black freedom struggle.

For Black folks in Memphis, the constancy of racial violence pervaded every facet of life. In his essay for the volume, Darius Young examines the 1917 lynching of Ell Persons, a Black woodcutter accused of murdering a white child. At the height of the lynching epidemic, Person’s murder was particularly grizzly. After arresting him on the basis of pseudo-scientific evidence, sheriff’s deputies handed Persons over to a mob. Both of the city’s local newspapers ran stories announcing his upcoming murder. Persons was lynched in front of ten thousand people. Young’s essay explores the various responses to the lynching, including refusing to enlist in the military, mobilizing to vote, and accessing the national platforms of organizations such as the NAACP to voice opposition to lynching and segregation.

In an era when depictions of Black life were dominated by racist images of “mammies” and “uncles,” the work of L.O. Taylor stands out. In her chapter, Beverly Bond introduces the reader to Taylor, a pastor and photographer who dedicated his life to filming and photographing Black life and culture in ways that revealed the rich, variegated interior lives of Black folks and the communities they constructed. Taylor spent almost fifty years chronicling Black life and culture in Memphis. Additionally, he taught generations of photography students how to “look at a thing and see more than what’s on the surface.” While he never spoke out directly challenging the reign of Edward Crump, the power behind the Bluff City’s segregated regime, his visual work provided a powerful counter-narrative to predominant notions of Black servility and ignorance.

In 1970, Maybelline Forbes became the first Black homecoming queen at Memphis State University, a year after she had been arrested during protests sponsored by the Black Student Association. Shirletta Kinchen’s layered exploration of this moment reveals the ways in which Black students, energized by the Black Power movement, harnessed the political organizing of young people across the city to confront white cultural norms on campus. Intervening directly into what Kinchen refers to as “beauty spaces”, Forbes’s victory reveals the power of collective action, as students sought to simultaneously insert themselves into the white spaces on campus “without sacrificing their black identity.” Her essay also reveals the ways Black students theorized about dominant aesthetic standards, and the ways to effectively reconstruct them.

For decades, the music industry in Memphis has been portrayed as a repository of racial parity, where Black and white musicians worked in harmony. Charles Hughes reminds us in his powerful essay that no corner of Black life lay beyond the shadow of segregation and economic inequality, despite the protestations of the city’s public relations machinery. Hughes’s essay on Rufus Thomas shows us how this racial privilege shortchanged Black artists. While Thomas achieved success as a singer at Stax Records, he was denied producer credit upon release of many of his records, despite having worked to produce them. Just as Black folks in other areas of Memphis had to navigate race-based economic inequality, Black musicians were not exempt from the same challenges, and fought to create more equitable circumstances.

Anthony Siracusa’s essay sheds new light on the tumultuous year of 1968, reconnects the War on Poverty programs to the city’s civil rights struggle, and shows how local activists (most notably James Lawson) often blurred the ideological lines between mainstream activists and young adherents of Black Power. Poverty lay at the heart of inequality in Memphis. To that end, civil rights activists eagerly partnered with the emerging anti-poverty organization in town to create a city-wide antipoverty infrastructure. Siracusa’s work also reveals the persistent institutional racism and resistance that led directly to the early conclusion of anti-poverty efforts in the Bluff City. Finally – and perhaps most crucially – Siracusa’s essay significantly revises the role and impact of federal surveillance on disrupting the Black freedom struggle in Memphis. FBI surveillance and disinformation efforts played a direct role in subverting the quest for greater freedom in Memphis. These efforts reverberate down to the contemporary moment, as Memphis police officials continue their illegal surveillance of Black activists.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.