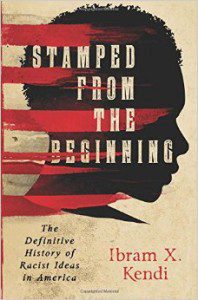

An Intellectual History of a Book Title: Stamped from the Beginning

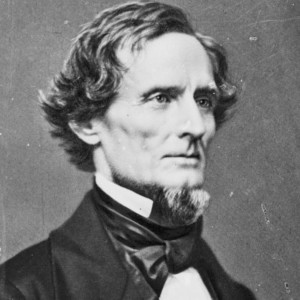

The main title for my new book, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, originated in the year 1860, on the floor of the U.S. Senate, from the voice of one the most infamous racists in American history. He is immortalized in statues across the U.S. South just as racist ideas have been immortalized in minds across America.

When Jefferson Davis reentered the U.S. Senate in 1857, he was deeply troubled by the sectional animosities prevalent in the country. To this Mississippi slaveholder, the newly emergent Republican Party had perverted the northern “mind” and alienated “the Northern people from the fraternity due to the South.” He did his best to avert secession, war and the Republicans, speaking across the country in the late 1850s about the complementary agricultural South and manufacturing North. He imagined slavery’s equalizing power. “Nowhere else will you find every white man recognized so far as an equal,” Senator Davis liked to say. He enjoyed erasing the South’s five million poor Whites.

On October 16, 1859, Senator Davis’s unifying crusade suffered a fatal blow. John Brown’s small interracial army attacked the Harper’s Ferry Armory in Virginia. The rebels tried and failed to instigate a slave rebellion. Brown was captured alive, unlike many of his men. Slaveholders still seethed and Senator Davis called the “murderous raid” an act of groundless Republican aggression.

On the day of John Brown’s execution—December 2, 1859—northern abolitionists mourned to the sounds of church bells for hours. At a mass meeting that night in Boston, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison sounded its purpose: “Today Virginia has murdered John Brown; tonight we here witness his resurrection.”

Proslavery southerners responded to the northern outpouring of mourning with an outpouring of terror against all things antislavery and Republican and northern and antiracist and freely Black in their midst. It was one of the most ghastly winters in southern history. By April 1860, Garrison had enough reports to publish the 144-page compendium, The New Reign of Terror in the Slaveholding States. What is the value of being united with people capable of such atrocities? Garrison demanded an answer.

Senator Davis argued back to Garrison’s abolitionists that they had terrorized the South, that they had issued an unconstitutional reign of terror against slavery. Senator Davis had emerged as the leader of all those planters still hoping their enslaving rights would be respected in the Union, and all those planters already cleaning their guns for secession.

On February 2, 1860, Senator Davis presented the southern platform of unlimited states’ rights and enslavers’ rights to the U.S. Senate. Southern enslavers needed these six resolutions passed if they were going to remain in the Democratic Party and the Union.

Senator Davis could have easily added a seventh resolution: the federal government should not use its resources to protect or aid Black people in any way. On April 12, 1860, Davis stood up and objected to a proposed bill that would appropriate funds for Black education in Washington D.C. “This Government was not founded by negroes nor for negroes, but by white men for white men.” The bill was based on the false assertion of racial equality, he argued.

Senator Davis began sharing a popular southern fairy-tale about the Black Land of Nod. He probably first heard this tale from Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright, Louisiana’s famed medical doctor and public intellectual. Dr. Cartwright had forged an influential literary career defending slavery with racist ideas. He was also securing medical work for himself by telling planters that healthy African people labored productively, loved slavery, and never resisted. In a popular 1851 article, Dr. Cartwright diagnosed runaways as clinically insane, and sluggish laborers as suffering from a disease he called dysesthesia.

Dr. Cartwright most prominently presented the story of the Land of Nod in 1860 in De Bow’s Review, the southern proslavery counterpoint to Garrison’s Liberator. Dr. Cartwright narrated how Black people were among the already created “living creatures” Adam and Eve were charged to rule. These pre-Adamite natural slaves inhabited the Land of Nod where Cain ventured after his banishment. Cain intermarried with the Black slaves of Nod. The racial mixing angered God, who determined “to destroy them in the flood.” Black people were taken on the ark alongside the other animals. Who did Dr. Cartwright cast as their overseer? Ham, Noah’s son. Cursed for disobeying Noah, God cursed Ham’s descendants into eternal Black skin and slavery.

Dr. Cartwright blended his racist idea of creation with the enduring racist idea of the curse of Ham. His new fairy-tale of the Black Land of Nod disseminated an old idea–nearly as old as the curse of Ham proslavery theory. It was an idea that had resided in the main halls of American science for decades; an idea that had traveled around the Western world; an idea that had been alive for centuries—the idea of polygenesis.

Ever since Europeans had their laid eyes on Native Americans in 1492, a people unmentioned in the Bible, they had started questioning the biblical creation story: that all humans stemmed from a monogenesis, or one creation. Some speculated that Native Americans had descended from “a different Adam.” By the end of the 16th century, Europeans thinkers had added African people to the list of species descended from a different Adam. Europeans thinkers had started considering polygenesis, or there being multiple creations—and each racial group had its own creation and were separate species of being.

In 1656, French theologian Isaac Le Peyrère published Men Before Adam. Christians tossed Le Peyrère in prison, but they could not stop the drift of polygenesis, or his book. Over in London, John Locke had secured a copy and questioned the monogenic origins of human species in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689). During the Enlightenment era, philosophers debated monogenesis and polygenesis. France’s Voltaire, Scotland’s Lord Kames and David Hume, and England’s Charles White made the racist case for polygenesis. It was during this withering debate over human creation that Thomas Jefferson asserted “all men are created equal” in 1776.

By the time Senator Davis began his political career in the 1840s, polygenesis scholars dominated the academy, namely UPENN anthropologist Samuel Morton. Polygenesis reigned over large swaths of the Western scientific community until it was overthrown in the late 1860s by a bombshell book, first released in 1859. “I can entertain no doubt, after the most deliberate study and dispassionate judgment of which I am capable, that the view which most naturalists entertain, and which I formerly entertained—namely, that each species has been independently created—is erroneous,” Charles Darwin wrote in the Origin of Species.

But in 1860, as Senator Davis stood before his colleagues, evolutionary theory had yet to evolve racist theory. Holding the day was still polygenesis (and racist monogenesis, or the racist idea that non-Whites were descendants of the original and superior White race, that was born in Europe’s Garden of Eden).

Senator Davis shared a much shorter tale on the Land of Nod to his colleagues at the U.S. Capitol on April 12, 1860. “When Cain, for the commission of the first great crime, was driven from the face of Adam, no longer the fit associate of those [Whites] who were created to exercise dominion over the earth, he found in the land of Nod those [Blacks] to whom his crime had degraded him to an equality.”

Senator Davis recited this story after confidently proclaiming to his peers: “the inequality of the white and black races” was “stamped from the beginning.” Racial inequality is “the will of God,” as “marked in decree and prophecy,” as “confirmed by history.”

This is the intellectual history of the book title, Stamped from the Beginning.

Racial inequality was not stamped from the beginning. Racist ideas were stamped from the beginning of America.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Up to now, Jefferson Davis seemed a bland character in my studies of the Civil War. This excerpt illustrates the aggressive apologist Jefferson Davis was in real life. Thanks, for this powerful article!