“Americans Have Carried American Hatred”: Black Intellectuals, Imperialism and Policing

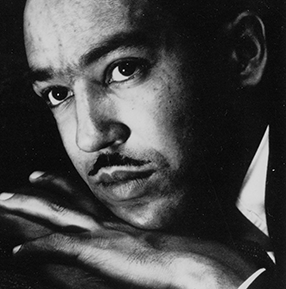

“Don’t you see no connection between atom-bomb-dropping in Japan and shin-kicking in Virginia?” asked Simple.

“No direct connection,” I said.

“Then you are not colored,” said Simple.

–Langston Hughes, “Not Colored,” 1965.

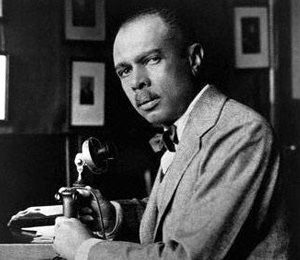

It was as if James Weldon Johnson had never left Florida. Born and raised in Jacksonville, Johnson had migrated to New York once it became clear that the Sunshine State was no place for a black man as ambitious as himself. But now, in the summer of 1920, he once again found himself in the midst of thousands of white southerners. All of them were armed, all of them were empowered as agents of law and order.

Johnson was in Haiti, not the U.S. South. Still, the connections between the two became clear to him soon after he arrived in Port-au-Prince on an investigative mission for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In his subsequent exposé on the exploitation of Haiti under U.S. occupation, Johnson noted that the most powerful men in Haiti were now white southerners. The head of the customs service, the financial advisor, and the superintendent of public instruction had all come from Louisiana. Another leading customs agent was from Mississippi. Perhaps most importantly, it seemed that a disproportionate number of the U.S. Marines stationed in Haiti were from the South. It alarmed Johnson that men used to the racial caste system of Jim Crow now had the authority to police Haitians whose ancestors had once overthrown slavery and colonial rule. It angered him to think that the position of power that those white southerners found themselves in was not coincidental.

The effect was predictable, too. In Haiti, Johnson found Marine after Marine willing to share with him the most sordid details of their role in the occupation of Haiti. Some told him of a comrade who used his rifle to bash in the brains of a Haitian boy caught stealing a bag of sugar. Others bragged about raping Haitian women and “hunting” Haitian peasants. They reported their actions with no hint of remorse or shame. To feel either did not make sense to them—the Marines were the law and the Haitians were the lawless. Hearing that assumption expressed time and time again, Johnson could not escape one overarching truth: “Americans have carried American hatred to Haiti.”1

As Keri Leigh Merritt explained in her recent post, professional police forces and modes of reinforcing white supremacy in the U.S. South were well-established when the United States began its occupation of Haiti. So, too, were other armed forces meant to police black and brown bodies throughout the world. In fact, the two went hand in hand. By 1928, the year that Alabama became the final state to stop leasing convicts, the United States had occupied numerous Caribbean and Central American countries including Haiti, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic. By then, U.S. Marines in Haiti had already reintroduced the corvée, a colonial system of forced labor that involved the worst horrors of a southern penal system meant to ensure black subservience. There were already clear parallels in the experiences of Haitians shot by U.S. Marines as they fled public works projects in rural Haiti and African Americans whipped to death in the mines outside of Birmingham.

If the material conditions of convict leasing and the corvée were clear, so too were the ideologies that reinforced each. As Mary Renda notes in Taking Haiti, the U.S. occupation of Haiti had its roots in a U.S. and southern culture of masculinity, paternalism, and interventionism. More than anything, though, it had its foundations in white supremacy and the state-sanctioned violence used to maintain it. Again, the U.S. Marines were more than willing to admit as much. In a letter to the assistant commandant of the Marine Corps, Colonel Littleton W.T. Waller, the descendant of Virginia slaveowners, boasted about his ability to assume leadership in Haiti. “I know the nigger,” he wrote with pride, “and how to handle him.”2

That statement and similar declarations revealed the interplay between cultures of imperialism and policing. Waller reveled in the exportation of U.S. racism that Johnson bemoaned. Of course, he would eventually return home. When he did, Waller and his fellow U.S. Marines brought back a culture of policing and racism that could not be uncoupled from the imperial violence inflicted on Haitians. Police forces in black and brown communities would come to resemble occupying armies by the latter half of the twentieth century. Policing would become wrapped in the same patriotic garb as soldiering. Both would come to rest on the underlying premise that African Americans or Muslims or Haitians or some other “other” had to be controlled with force that could not and would never be used against any other population.

This is the history that lives with us today. It matters in Minneapolis/St. Paul, the home of the murdered Philando Castile and tens of thousands of Somalis, many of whom left their country after the failure of U.S. military intervention in Somalia during the 1990s. It matters in Baton Rouge, a city where Alton Sterling died for selling CDs in a state that has long imprisoned more people per capita than any other state or country in the world. It matters in Dallas, where police used a robot equipped with explosives to end a standoff with a disillusioned veteran who just returned from the war on Afghanistan. The justifications, the technologies, the casualties. What distinguishes them at home and abroad? What separates the cultures of imperialism and militarism from domestic policing?3

Nothing. That is the answer that more and more scholars and activists are bringing to light. It is the answer that black intellectuals including Langston Hughes articulated decades ago.

Two years before his death, three decades after he visited occupied Haiti, and eight years before the end of the Vietnam War, Hughes published Simple’s Uncle Sam, a collection of short stories starring Jesse B. Semple, a southern-born black Harlemite better known as “Simple.” In one story, Simple tells his friend about a childhood run-in with Mr. Winclift, one of the meanest white men back home in Virginia. The man had kicked Simple in both shins when he tried to retrieve a lost ball from the man’s yard. Even with the distance of time and space, the memory still stuck with Simple. It bothered him because he knew from family back in Virginia that Winclift was still abusing black people in his town.

Simple told his buddy that Winclift had recently slapped his cook for burning his biscuits. He predicted that Winclift would also get away with that assault, though. Despite the fact that the black domestic had secured a warrant for the arrest of her assailant, Simple knew that “she will just stay slapped, that’s all, like I stayed kicked.” He understood that they both would have to confront the fact that violence could be sacrosanct and state-sanctioned; the law could give men like Winclift the power to take out their rage, their insecurities, and their fears on black bodies.

Simple understood that the same was true across time. And it was true across space. Simple proceeded to tell his friend that men like Winclift were the reason that the Japanese wanted no part of Americans. They knew Hiroshima was not far from Jim Crow Virginia.

But his friend did not understand. The story ends with Simple objecting to his friend calling his reference to Japan a non sequitur. Perplexed, Simple asked him, “you see no connection between atom-bomb-dropping in Japan and shin-kicking in Virginia?” “No,” his friend replies. No direct connection at all.

“Well,” Simple concluded, “then you are not colored.”4

- James Weldon Johnson, “Self-Determining Haiti,” The Nation (1920), 18. ↩

- Mary A. Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation & the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915-1940 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 100. ↩

- On the symbiotic relationship between the technologies of empire and those of the police state, Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009). ↩

- Langston Hughes, “Not Colored,” in The Collected Works of Langston Hughes: Later Simple Stories, Volume 8 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2002): 236-237. ↩

Brilliant writing and research!

One of the best recent articles on the subject. Thanks!