Afro-Colombians and the Peace Agreement in Colombia

On the evening of October 2, 2016, the whole world was in absolute shock. The Colombian people rejected a historic peace agreement between the government and the country’s leftwing, guerrilla organization, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), in a plebiscite by the narrowest of margins, a matter of barely more than 50,000 votes.

If the agreement had passed that evening, it would have ended more than half a century of civil war in Colombia. To be clear, the peace deal would have directly affected the lives of Colombia’s most marginalized communities who bear the brunt of the war, among them poor, urban and rural Afro-Colombians, of which 78.5% live below the poverty line as of 2011 (compared to the national average of 49.2%).

Although Afro-Colombians constitute about 10.6% of the national population, they are disproportionately the victims of murders (primarily at the hands of rightwing paramilitary forces) and violent, forced displacements in the countryside, caught in the middle of fighting between guerrillas, the state, and paramilitaries often backed by the state and financed by drug-traffickers and multinational corporations. According to a government survey conducted in 2010, for example, about 22.5% of the displaced population identified as Afro-Colombian. The figure is unquestionably bigger, for many fear reprisals and retributions if they register themselves as “officially” displaced.

Unsurprisingly, the peace deal was supported overwhelmingly in predominantly Afro-Colombian regions like the Pacific Coast where about 80% of the population is Afro-Colombian. With the emergence of rightwing paramilitary organizations and powerful drug-trafficking rings beginning in the mid-to-late 1990s, the Pacific Coast of Colombia has become ground zero of the war in Colombia. In 2013 alone, the government reported that 63.4% of all displacements in Colombia occurred in the four departments of the Pacific Coast. After the plebiscite, it was revealed that eight of the top ten municipalities in Colombia—with the highest pro-peace votes (more than 93%)—were located in the western, Afro-Colombian Pacific region.

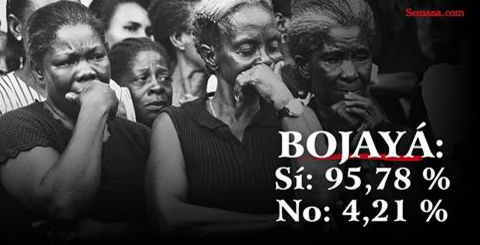

Among the municipalities with the highest pro-peace votes was a small, Afro-Colombian river town called Bojayá, located in the rural, Pacific coastal department of Chocó. On May 2, 2002, Bojayá became the epicenter of the armed conflict in Colombia when devastating fighting erupted between the FARC and paramilitaries from the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) in their town. On that morning in May, hundreds of families fled to the town church to seek refuge from the crossfire. While paramilitary soldiers hid around and behind the church, the FARC launched an improvised mortar full of explosives and shrapnel that hit the church, killing 119 villagers, among them many children and elderly.

According to an investigation by the United Nations, the national army of Colombia allowed paramilitaries to enter the region without any trouble. Despite calls for help and an alert from the Ombudsmen, the army did not appear until well after the massacre. About 5,771 people, the majority from Bojayá and surrounding villages, were forcibly displaced to the capital of Chocó in that single month of May alone.

Bojayá is undoubtedly one of the central sites of Colombia’s long and tragic history of war and armed conflict. And despite this, or perhaps, better yet, because of it, this small, rural Afro-Colombian town had the fourth highest percentage of peace votes in the entire nation at 95.78%. A few days after the rejection of the peace plebiscite, the victims of Bojayá released a collective statement demanding the country respect and ratify the peace agreement. “We, the victims of Bojayá, have suffered the brutality of the war and for that reason we voted YES to Peace,” they declared.

Much was at stake for poor, rural and urban Afro-Colombians in the peace deal. Besides ending the formal war between the FARC and the government, the final peace agreement included an “Ethnic Chapter” that explicitly recognized that the injustices inflicted by black and indigenous communities were the historic “product of colonialism, slavery, exclusion, and dispossession from their lands, territories, and resources,” and guaranteed protection, participation, and self-government to these communities. This inclusion was the product of concerted organizing and mobilizations by various Afro-Colombian organizations including the Afro-Colombian National Council of Peace, the Association of Small and Medium Miners of Chocó, the National Coordination of Afro-descendent Organizations and Communities, Chao Racismo, and other black and indigenous organizations. In June 2016, representatives of these groups met in Havana with FARC leaders and government peace negotiators to demand the inclusion of an “ethnic” focus in the accords.

On November 12, 2016, about a month or so before the lifting of a ceasefire between the FARC and the government set on December 31, 2016, both parties announced that they had reached a new peace deal that integrated changes and proposals from the opposition. The new peace deal will not be put up to another national plebiscite, but will now be debated and voted in the Colombian Congress. Fortunately, for so many Afro-Colombian families, organizations, and communities, the hard-won “Ethnic Chapter” remained in the final version of the peace agreement.

As Afro-Latino writer and Divinity Student at Duke University Daniel José Camacho wrote, “I’m inspired by the Colombians who didn’t let the plebiscite results stop them.” In the wake of our own national shock in the United States earlier this November, perhaps the struggles of Afro-Colombians who continue to mobilize and organize despite the highest of odds against them can offer some guidance.

Yesenia Barragan is a historian of race, slavery, and emancipation in Colombia, Afro-Latin America, and the Atlantic/Pacific worlds. She received a Ph.D. in Latin American and Caribbean History from Columbia University. She is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Society of Fellows at Dartmouth College. Follow her on Twitter @Y__Barragan.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.