“African” Men and Women: Patriarchy and Pan-Africanism

This is the third day of our roundtable on Russell Rickford’s book, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination. We began with introductory remarks by Reena Goldthree on Monday, followed by remarks by Fanon Che Wilkins on Tuesday. In this post, blogger Ashley Farmer explores the gendered and masculinist dimensions of Pan-Africanism, Black Power and the black independent school movement.

Ashley Farmer is a historian of African American women’s history. Her research interests include women’s history, gender history, radical politics, intellectual history, and black feminism. She earned a BA in French from Spelman College, an MA in History from Harvard University, and a PhD in African American Studies from Harvard University. She is currently a Provost Postdoctoral Fellow in the History Department at Duke University. In August 2016, she will be an Assistant Professor in the Department of History and the African American Studies Program at Boston University. Her first book, What You’ve Got is a Revolution: Black Women’s Movements for Black Power (forthcoming, UNC Press), analyzes African American women’s intellectual production to uncover how they shaped gender constructs and political organizing in the black power movement.

Ashley Farmer is a historian of African American women’s history. Her research interests include women’s history, gender history, radical politics, intellectual history, and black feminism. She earned a BA in French from Spelman College, an MA in History from Harvard University, and a PhD in African American Studies from Harvard University. She is currently a Provost Postdoctoral Fellow in the History Department at Duke University. In August 2016, she will be an Assistant Professor in the Department of History and the African American Studies Program at Boston University. Her first book, What You’ve Got is a Revolution: Black Women’s Movements for Black Power (forthcoming, UNC Press), analyzes African American women’s intellectual production to uncover how they shaped gender constructs and political organizing in the black power movement.

***

In April 1969, ten pupils gathered in an East Palo Alto home for their lessons. They were the inaugural class of the Nairobi Day School, an independent black community education center that local activist Gertrude Wilks created. For the better part of the preceding decade, Wilks had worked tirelessly to integrate local public schools. The rise of Black Power nationally, and the fervor of Stokely Carmichael’s local speeches, made her strike out on her own. During his visits to East Palo Alto, Carmichael encouraged residents to take over public schools or form independent ones. Wilks followed his advice, opening Nairobi, a community-based black academy, replete with courses on African history, economics, and black consciousness. The founding of the Nairobi Day School was paradigmatic of the education movement in the Black Power era, one in which black activists, frustrated with the racist public school system, created parallel educational institutions. It also reflected the gender dynamics of their black independent school movement: one in which black men were the national spokespersons for separatist schools while black women founded and operated these grassroots institutions.

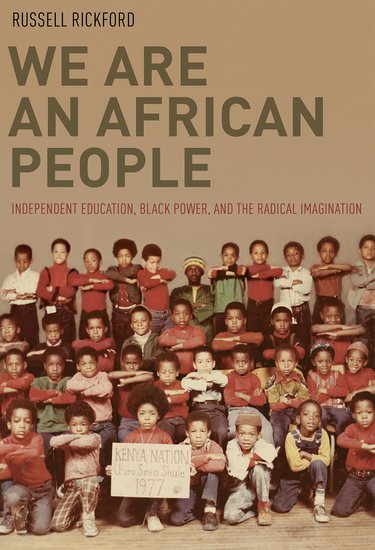

In We Are an African People, Russell Rickford documents the rise and fall of independent schools like Nairobi. He traces the physical and ideological evolution of separate black-run educational institutions, beginning with black activists’ efforts to control their local public schools in the 1960s, to the rise of a network of separate black schools in the early 1970s, to the precipitous decline of these institutions in the late 1970s. The book chronicles this Black Power “submovement” in which activists and intellectuals saw independent black schools as “a way to redeem the process of formal learning” and as a way to “prefigure black cultural and political sovereignty” (p. 4). Undergirding this history, however, is a story of how activists’ ideas about manhood and womanhood shaped popular and pedantic understandings of black education, Pan-Africanism, and Black Power.

Throughout the book, Rickford demonstrates how the black independent school movement took on a format in which men theorized and women organized. He argues that black nationalists viewed black women as “natural teachers,” and, as a result, they “bore primary responsibility for instruction” at many community schools (p. 76). This was the case at the Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School and the Committee for Unified Newark’s African Free School, among others. This gendered hierarchy codified patriarchy in the black independent school movement. It also (somewhat ironically) meant that black women wielded significant power and influence as the leaders of these schools. Rickford is careful to note that black women did found and run their own schools. However, he maintains that, even within these women-led and run spaces, male-dominated approaches to “nation building” reigned.

Indeed, We Are an African People turns on the persistent claim that patriarchy undermined activists’ quest to reclaim black intellectual and cultural autonomy. Black Power-era activists and intellectuals viewed independent black community schools as spaces to preform “blackness” and cultivate cultural behaviors designed to “re-Africanize” black youth. Redefining manhood and womanhood was a critical part of this project. To that end, activists developed distinct and idealized beliefs about men and women’s roles. Men were the “natural” leaders of the black nation and women were responsible for education, social development, and “having babies for the revolution.” Rickford argues that this was both a theoretical and practical weakness of the independent school movement. Such a position undermined activists’ goal of creating a new social order by reifying rather than radicalizing traditional gender roles. This hierarchy also limited the effectiveness of powerful women organizers.

Rickford points out that black women both codified and challenged this patriarchal social order. He notes that Amina Baraka, wife of Black Arts poet Amiri Baraka and head of the African Free School, actively collaborated “in [men’s] attempts to regiment women’s personal habits, dress, and behavior” (p. 154). As activists’ ideas about Africa and Pan-Africanism evolved, however, so too did women’s vocal rejection of patriarchy. For example, Tayari Kwa Salaam, a leader in Ahidiana, a New Orleans-based organization and school, eventually disavowed this “narrow cultural nationalist worldview” and adopted a feminist position on women and education (p. 156).

We Are an African People offers a much needed and sobering account of how patriarchy and sexism undercut the potential of Black Power, Pan-Africanism, and the black independent school movement. However, Rickford leaves the reader wondering about the overall evolution of ideas about gender roles within the movement. For example, he is careful to note that as activists “abandoned reductionist visions of the African World” they sought more “rigorous frameworks and, in some cases, engage[d] feminist and proletarian” frameworks (p. 131). One assumes that this accounts for the shifts in perspectives of women like Baraka or Salaam, but it is not entirely clear. More attention to exactly what constituted these “feminist” struggles would have helped the reader understand this ideological shift.

On this same note, the reader is left wondering what effect, if any, this had on the perspectives of men. Some of the most ardent proponents of women’s “submissiveness,” like Maulana Karenga and Amiri Baraka, renounced this position in the early 1970s.1 How did this transform the independent school movement and the imagined community that they were trying to create? Rickford gestures to their evolution in the Epilogue, but readers might desire a more nuanced understanding about how this evolution in thinking transformed male activists’ perspectives. Finally, Rickford argues that while women found ways to subvert this patriarchal order, they did so mostly “in private.” However, there is evidence to suggest that black women publicly debated the intersection of gender roles and political ideology even within the most conservative organizations.2 Given their writings on this issue, one wonders if Rickford undersells their public push back. Or, in other words, what is lost in his framing of the nationalist gendered imaginary as a virtually uncontested public space?

Nevertheless, Rickford has produced a groundbreaking and impeccably researched book that transforms our understanding of Black Power and Black education. We Are an African People is also a prime example of how the new Black Power histories can and must address how sexism and patriarchal political ideologies blunted nationalist efforts. While readers may long for more nuanced approach to how women navigated gender constraints, Rickford makes it clear that the story of the independent school movement, Pan-Africanism, and Black Power cannot be told without them. He also opens up the opportunity for future scholars to map the real and imagined gendered contours of nationalism and Pan-Africanism.

- Maulana Karenga, “A Strategy for Struggle” The Black Scholar, 5, no. 3 (1973): 8–21; Amiri Baraka, Amiri Baraka, “The Meaning and Development of Revolutionary Kawaida. ↩

- Ashley Farmer, ““Renegotiating the ‘African Woman’: Women’s Cultural Nationalist Theorizing in the Us Organization and the Congress of African People, 1965-1975,” Black Diaspora Review 4:1 (Winter 2014): 76-112. ↩

“Rickford argues that this was both a theoretical and practical weakness of the independent school movement. Such a position undermined activists’ goal of creating a new social order by reifying rather than radicalizing traditional gender roles. This hierarchy also limited the effectiveness of powerful women organizers.”

I can see how this would be a problem.

I like “Some of the most ardent proponents of women’s “submissiveness,” like Maulana Karenga and Amiri Baraka, renounced this position in the early 1970s.1 How did this transform the independent school movement and the imagined community that they were trying to create? Rickford gestures to their evolution in the Epilogue, but readers might desire a more nuanced understanding about how this evolution in thinking transformed male activists’ perspectives. Finally, Rickford argues that while women found ways to subvert this patriarchal order, they did so mostly “in private.” However, there is evidence to suggest that black women publicly debated the intersection of gender roles and political ideology even within the most conservative organizations.” Exactly! Most African centered schools I am familiar with were both created and led ideologically by African women.

I think the questions Dr. Densu brought up are important. There was certainly a range of approaches in terms of women and gender roles as related to political ideology, organizing, and institution building. Some were more conservative and clandestine while others were more strident. Certainly, time and organizational philosophy played a part in terms of the level and tone of women’s resistance.