African American Novelist Frank Yerby’s Writings on Race

African American novelist Frank Yerby grew up in Augusta, Georgia, where he attended Paine College. Later he attended Fisk University and taught briefly at Southern University and Florida A&M. Between 1946 and 1985, Yerby published thirty-three novels–three of which became major motion pictures and one of which became a television film. His first novel, The Foxes of Harrow (1946), sold 500,000 copies in its first two months of release, and a year later in 1947, it appeared on the big screen starring Rex Harrison and Maureen O’Hara.

Even with his success, many critics have maligned Yerby’s work and career because he chose to write popular fiction and what he termed “costume novels” that were centered on white characters rather than protest literature in the vein of Richard Wright. Yerby began his career writing protest literature, and his story “Health Card” (1944) won the O’Henry Memorial Award in 1944. However, his early novels, from 1947 to the mid-1960s, subvert protest for the outward adornments of popular fiction.

Critics such as Langston Hughes, Blyden Jackson, and others initially praised Yerby for his success with The Foxes of Harrow, a novel that traces the rise and fall of a white Irishman, Stephen Fox, in New Orleans between 1825 and 1865. Arna Bontemps and Alain Locke both praised the novel’s achievement, but each also hoped that Yerby would turn his focus to contemporary social issues in the future. Yerby did not do this until later in his career with novels such as Speak Now (1969), his first to have a Black male character at the center of the narrative. Yerby’s continual deployment of the “costume novel,” a genre that appeared to play into the “moonlight and magnolia” image of the Old South, caused many Black critics to dismiss his work, and in 1958, it even led Robert Bone to call Yerby “the prince of pulpsters.”

On the surface, Yerby’s novels appear to uphold the image of the Old South perpetuated by Margaret Mitchell, Thomas Nelson Page, and other writers. Yet he works to deconstruct the myths that uphold that image. In 1968, Darwin Turner claimed that Yerby’s dismantling of these myths was perhaps his greatest contribution to American literature. Yerby challenged the myths of the Old South in his protest stories; but, in his novels, this critique was hidden beneath the veneer of stock images that play into his majority white, middle-class readership’s views on race.

Yerby’s deconstruction of the myth that Southern men were “aristocratic, cultured, brave, and honorable” occurs within the opening pages of The Foxes of Harrow where Stephen Fox, the man who becomes a wealthy plantation owner, refers to himself as a “Dublin guttersnipe” because of his lowly birth. Even though Stephen can rise to prominence, all white characters do not move from one social class to another. Throughout his career, Yerby populated his “costume novels” with poor whites in the antebellum and Reconstruction South. He also illuminated the “legal fictions” that separate individuals based on the color of their skin.

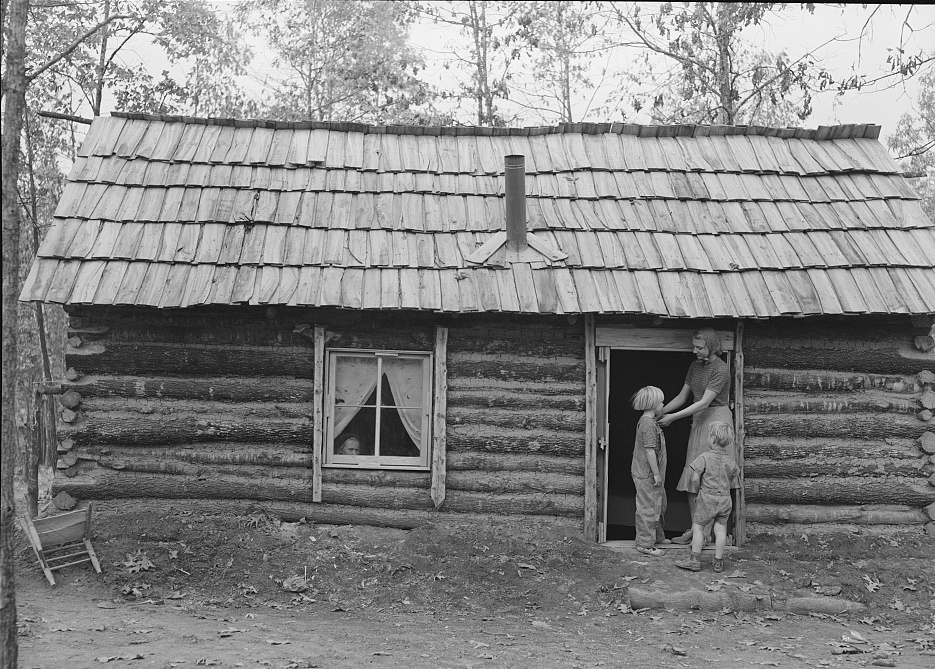

In Black Reconstruction in America (1935), W. E. B. Du Bois argues that the causes of the Civil War stemmed from “the South[’s determination] to make free white labor compete with Black slaves, monopolize land and raw material in the hands of the political aristocracy, and extend the scope of its power.” Yerby was acutely aware that the majority of southern whites were not wealthy landowners, and not all southern whites owned slaves. In fact, Yerby directly points out in The Foxes of Harrow that before the Civil War, men read Hinton Helper and George Fitzhugh. Yerby summarizes Helper’s argument by stating, “only two hundred and twenty-five thousand men actually held slaves [. . .] while in the pine barrens and the clay hills and the swamp bottoms white men rotted in idleness.” These “white men” were “poor whites,” men who–according to historian Keri Leigh Merritt–did not own land or slaves and were under constant surveillance from wealthy landowners before the Civil War.

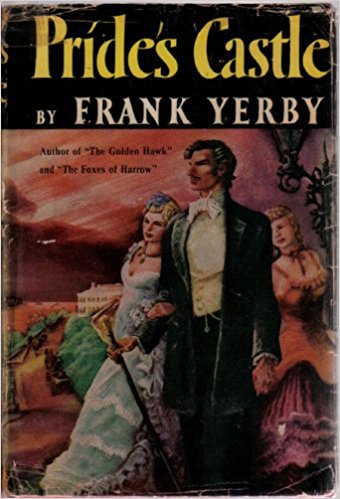

In his “costume novels,” Yerby highlights the class distinctions between poor whites and wealthy landowners and how those differences flattened during Reconstruction when white labor competed with Black labor. Pride Dawson, the eponymous character of Pride’s Castle (1949), is a poor white who rises to wealth and prominence in the Northeast during Reconstruction. Yerby’s second novel, The Vixens (1947), takes place during Reconstruction. It chronicles the New Orleans Mechanics Institute and Colfax massacres, and shows how wealthy landowners maintain their power and position by pitting poor whites against freed Blacks. Yerby begins the novel by setting the stage immediately after the war, demonstrating how the wealthy want to keep things as they had “been since the beginning of time: Master and man, black man owned, white men out in the piney barrens, debased and starving.”

Even though these landowners want to keep some white men “debased and starving,” they use them to invoke fear and terror in the Black community. From “smoky offices,” wealthy characters like Hugh Duncan conduct terrorist plots against free Black communities in New Orleans, Colfax, Bossier Parish, and elsewhere. While not wanting to be equal with the poor whites, Hugh Duncan nevertheless employs them for his purposes so that he and others can maintain power and control.

Benton’s Row (1954) is perhaps Yerby’s most in-depth engagement with poor whites and the ways that wealthy landowners’ views of them changed after the Civil War. The novel tells the story of Tom Benton and his progeny from before the Civil War through the early twentieth century. In the lead up to the war, Yerby notes that the South “will need the common white” to help against the North. He continues by highlighting the interconnectedness of poor whites and wealthy landowners and how the wealthy were lying when talking about poor whites as a “different breed, children of redemptioners, bondsman, debtor-prison scourings” to Yankee guests because they needed the lower classes as soldiers to maintain their position of power, and they knew that the lies they perpetuated were merely myths to maintain class separation.

As Tom is traveling with his friend Randy while discussing slavery, Randy points out an emaciated child and tells Tom that she is the argument against slavery because she is white and “a direct victim of slavery.” Before the Civil War, affluent whites sought to maintain control by limiting labor opportunities for poor whites. As such the young child looks the way she does, according to Randy, because she has no economic value to add to the landowner. She and her parents would want wages that disrupt the free, enslaved labor that landowners maintained.

Returning home after the war, Tom’s son, Wade, is accompanied by a poor white, Oren Boscomb. As they head home, Oren tells Wade he is now free and will make something of himself with Wade’s help. Wade asks him why Oren needs him, to which Oren replies:

My folks warn’t much: white trash, swampers, and such-like. No war record. Course I fought like hell, but I fought for Rebs as much as I did Feds. Fought for me. What did I care if folks kept their niggers or not? Got caught, either side would of hung me out of hand for robbing the dead, bushwhacking, foraging and stealing. But all that’s finished. Everything’s plumb busted to pieces. Man like me’s got a chance now, if he’s smart. And damned if this thing on my shoulders don’t work right pert good.

Oren’s freedom originates from the economic opportunities arising from the remains of the war. As Merritt shows, the South’s “economic ruin” allowed poor whites to seek landownership and take advantage of the downfall of some of the wealthy landowners. Economic ruin also flattened some of the distinctions between poor and affluent whites, pitting them, economically, against freed Blacks.

Throughout his work, Yerby explored these issues and illuminated the ways that capitalism influenced slavery and class relations. Even though the moments come between scenes of lustful passion and violence, they nevertheless serve as a way to critique the mythology of the South that arose during the latter part of the nineteenth century, and to instruct white middle-class readers. In this way, we can see how novelist Frank Yerby interrogated and deconstructed historical myths through his writing in an effort to shift his readers’ perspectives on race.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

A brilliant and prolific African American writer, obscure no more. We also found Yerby’s reimagining of the early Christian mythology in the novel JUDAS MY BROTHER to be an extraordinary text, even though religious critics deemed it controversial. Thank you for this!

Yvonne,

Thank you for reading. I just finished The Saracen Blade, and his comments on religion are very thought provoking. I also see a lot of the same discussions I mention above in his texts about Medieval Italy and even the Caribbean. He’s doing a lot underneath the surface that needs to be excavated.

A writer friend and I ocassionally mention Yerby in our emails in one way or another, if for nothing else, by influencing us by the force of his narratives. Beneath the lust and violence, there was always a fine writer at work illuminating the South we often write about in its modern version. Great to see a huge nod to him.

Raymond:

I totally agree. There are some amazing passages. I’m thinking about a couple from The Vixens that get into the head of Sabrina come to mind.

My ancestors Jean-Baptiste and Louis-Charles Roudanez turn up in the Vixens. They published/founded the New Orleans Tribune, America’s first Black daily. One of America’s first sustained civil rights movements coalesced around the Tribune. Yerby: “There’d be a pitched battle in the streets. New Orleans is howling mad, Sabrina. There’s too much going on. That little Yankee dentist, A.P. Dostie, stirring up the blacks. Those Roudanez brothers-foreign negroes born, I’v been told in Santo Domingo, where n—–rs make a sport of killing whites–stirring them up worse.” The Roudanez brothers turn up on other pages as well. My mother claimed to have first learned about my father’s Black lineage when she read the Vixens in 1948. My father, also named Louis Charles Roudanez, never acknowledged his heritage.