African American Diplomacy and Disruptive Activism (Athan Biss)

This is a guest post by Athan Biss, a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research and teaching interests include Race and U.S. Foreign Affairs with a particular focus on African American history, U.S.-Soviet relations, and the history of cultural diplomacy. He is currently writing a dissertation on African American diplomacy from the Early Republic to the Cold War. His essay, “The Voice of the Race: The Fisk Jubilee Singers and African American Musical Diplomacy,” was awarded the 2014 Jan Lucassen Award by the European Social Science History Conference.

***

African American activists affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement sparked heated debate by targeting the campaign events of Democratic presidential candidates. While BLM has since taken aim at Republican candidate Jeb Bush, the initial criticism, voiced on cable news, social media, and on liberal blogs, focused on the strategic logic of attacking sympathetic, progressive “friends” of the movement. Others took issue with the manner in which the protests were carried out. Couldn’t the protestors adopt a more reasonable tone in order to seek common ground?

In addition to patronizing black activists, these responses ignore history. In the most celebrated and successful chapters of African American protest from abolitionism to the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans have, by necessity and by design, embraced confrontational tactics. As Ashley Farmer’s recent blog-post makes clear, the strategy and tactics of democratic disruption have long been at the heart of African American civil rights activism. This is equally true of African American international engagement. As second-class citizens who faced discrimination, disenfranchisement, and violence in the land of their birth, African Americans repeatedly looked abroad for allies. As consummate outsiders, African Americans had to repeatedly ‘crash the gates’ of international diplomacy in order have their voices heard. In the two decades before the Civil War, the U.S. State Department and the Supreme Court effectively stripped African Americans of U.S. citizenship. The denial of passports to African Americans, which predated the final Dred Scott decision, affirmed Justice’s Taney’s infamous assertion that African Americans possessed “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”1 As a “stateless” people, African Americans continued to fight for recognition of their basic human rights by tapping into the era’s transnational reform networks. In the process, antebellum activists pioneered a new form of diplomacy in which non-state actors working outside of the normal channels of statecraft forced a response from U.S. representatives.

A surge in international forums facilitated the development of African American diplomacy. In the early 1840s, London hosted two World Antislavery Conventions under the auspices of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. African American abolitionists took part in both meetings as members of integrated American delegations.2 African American activists noted the growing support for their cause in the realm of global public opinion. “The nations of the world are moving in the great cause of universal freedom, and some of them at least will, ere long, do you justice,” Henry Highland Garnet, a prominent editor and abolitionist, predicted at the 1843 National Negro Convention in Buffalo, New York. In Garnet’s estimation, American slaves needed to capitalize on the favorable international climate by ramping up their resistance. In the meantime the black leaders must continue to campaign to isolate America by lobbying European powers to place “their broad seal of disapprobation” upon slavery.3 Significantly, African Americans also attended international conferences dedicated to temperance, peace, moral reform, and evangelism.

Despite being barred from segregated American delegations, African Americans still found ways to participate in these forums, which served as platforms to internationalize the plight of their people. Their participation frequently proved disruptive. For example, Frederick Douglass attended the 1846 World’s Temperance Convention in London, not as part of the American delegation, but as an at-large delegate representing Newcastle. When Douglass took the floor to denounce slavery, one of the American delegates, an eminent doctor of divinity from New York, publicly objected to his speech as a violation of “the law of reciprocal righteousness.” Douglass, he continued, was an “intruder” who “smuggled” anti-slavery into a discussion of temperance and impugned the reputation of American Christians.4 Douglass remained unapologetic for offending of the sensibilities of white Americans or trangressing the unwritten laws of gentlemanly conduct. African American activists consciously courted opprobrium for disregarding the norms of middle class Victorian society and high diplomacy, because they correctly judged that the changes they sought would be impossible to achieve within the constraints of the existing system. Moreover, as savvy strategists, African Americans understood that controversy attracted publicity, and that publicity, in turn, could be leveraged to effect political change.

African Americans who encouraged and trumpeted foreign criticism of American domestic policies can therefore be understood as engaging in a form of anti-diplomacy. Rather than studiously avoiding offense, African American race diplomacy courted conflict. Rather than maneuvering to spare the United States from embarrassment on the global stage, African Americans saw shame as a necessary catalyst for reform. This strategy of disruption achieved its most spectacular result, ironically, at the most mundane of forums: an international statistics conference. In July of 1860, ninety representatives from twenty-four nations and six continents descended on London for the second International Statistical Congress.5 The congress represented an early endorsement of the power of intellectual exchange to foster “friendly relations […] and the maintenance of peace and good-will among the nations.”6 Given the high-minded spirit of the congress, few of the bespectacled delegates could have predicted that it would become the scene of a diplomatic incident that would inflame Anglo-American tensions.

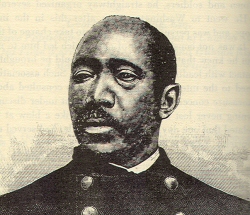

President James Buchanan sent two official U.S. delegates to the congress. Unbeknownst to the U.S. State Department, however, a third American, the abolitionist Dr. Martin Delany had also crossed the Atlantic and obtained a spot in the Canadian delegation. Delany, who was born free in Virginia and spent most of his adult life in Pittsburgh, had emigrated to Canada in 1856. As one of the first African Americans admitted to Harvard Medical School and a member of the Royal Geographical Society, Delany was well qualified to join the other assembly of statisticians. As a practitioner of the strategy of disruption, Delany viewed the high-profile congress as the perfect venue to expose American hypocrisy to the world. Like Douglass at the World’s Temperance Convention, Delany turned the “statelessness” of African Americans to his advantage and in so doing illustrated the inability of the American government to fully suppress independent African American diplomacy.

The congress opened to great fanfare on the afternoon of July 16. Following Prince Albert’s convocation, Lord Henry Brougham, an octogenarian veteran of the British abolitionist movement, rose from his seat. Breaking decorum, Brougham directly addressed George M. Dallas, the American Minister to Great Britain who had been invited to attend the first day of the congress as a guest. “I beg my friend Mr. Dallas to observe there is in the assemblage before us a Negro and hope the fact will not offend his scruples,” Brougham announced. Taken aback, Dallas noticed a “sable gentleman seated conspicuously in the centre of the crowd.” Adding to the American Minister’s mounting discomfort, Delany then stood and begged permission from the Prince to assert another “interesting statistical fact.” Looking squarely at Dallas, Delany declared, “I am a man!” As the hall echoed with applause, Dallas stewed in silence.

The entire scene, as Dallas promptly reported to Washington, struck the diplomat as a “premeditated contrivance to insult the country which I represented, and to provoke, if possible, for the benefit of the audience an unseemly discussion between the American Minister and the Negro.”7 Dallas used racially charged language to paint himself as the victim of an undignified and uncivilized surprise attack. Brougham had lay in wait “secretly whetting his tomahawk,” biding his time until he could “pounce from a covert and with a yell” to scalp the unsuspecting Dallas with the aid of a “sable phenomenon.” Such savagery, Dallas argued, could only be met with “calm and well digested preparation.”

When such attacks on the nation’s honor took place in “conspicuous theatres of public life,” Dallas continued, the response of the United States assumed added gravity. Dallas reasoned that it “would have been great folly to imply, by word or act, that the question of slavery could legitimately be discussed before the American minister at a European conference of any sort.”8 Wary of setting a dangerous precedent, Dallas held his tongue despite his firm conviction that the British government should be held responsible for the insult. Dallas worried that a misstep would invite further “overreaching or entrapping diplomacy.”

If Brougham and Delany had indeed set out to embarrass the United States, gin up controversy, and draw publicity, their plan had thus far worked to perfection. The State Department, which in the past had studiously avoided drawing attention to African American diplomacy, could not ignore the fallout from the International Statistics Congress. Secretary of State Lewis Cass asserted that because incident occurred at “a semi-official meeting of the highest character composed of delegates from almost every part of Christendom and upon which the public attention is earnestly directed,” the United States had “just cause for complaint.” With the tacit approval of the British government, Brougham and Delany had diverted the “praiseworthy” congress “from its appropriate functions into a theatre for insulting a friendly power.”

Cass agreed that the incident constituted “a reproach upon a large portion of the American people, among whom slavery is an established institution, and upon a still larger portion, among whom I am one, who consider the negro race an inferior one and who repudiate all political equality and social connection with its descendants.” The disruption of the International Statistical Congress, Cass argued, was far from an isolated incident. Rather, it represented “another contribution to the system of attack, of vituperation rather, which in high places and low throughout England is carried on with unsparing severity against the United States.” These attacks, “brought over the ocean by every packet […] cannot fail to be followed by unhappy effects upon the intercourse of the two countries.” Cass noted that the days immediately following the event marked the appropriate time to register an official complaint with the British Foreign Ministry. Now, two months after the fact, it was too late to pursue this course.9

Delany’s choreographed disruption of the international statistical congress drew attention to the centrality of racism to American foreign policy. Not for the last time, American foreign policy makers faced a public relations crisis of their own making. And African Americans, abandoned by the country of their birth, successfully brokered an alliance with a U.S. rival. While the State Department invoked the written and unwritten laws of international diplomacy to silence discussion of the internal affairs of the United States in global forums, African Americans continued to seek global forums to internationalize their struggle for equal rights. As with later leaders, following the rules was not an option. Disruption represented the only viable strategy for change.

- Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857) https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/60/393 (accessed June 24, 2015) ↩

- Charles Remond, an African American abolitionist from Salem, Massachusetts attended the inaugural 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention as part of the official American delegation. Three years later, the African American minister J.W.C. Pennington joined another robust American delegation that traveled to London for the Second World Anti-Slavery Convention. ↩

- Henry Highland Garnet, “An Address to the Slaves of the United States, Buffalo, NY, 1843” http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=etas (accessed June 12, 2015). ↩

- Frederick Douglass, Autobiographies (New York: Library of America,1994), 691. ↩

- Vienna hosted the first International Statistical Congress in 1856. “Recent Events,” The Morning Post (London), July 18, 1860. ↩

- James T. Hammack, “Report to the Statistical Society on the Proceedings of the Fourth Session of the International Statistical Congress, Held in London, July, 1860,” Journal of Statistical Society of London Vol. 24, No. 1 (March 1861): 17. ↩

- George M. Dallas to Lewis Cass, No. 246, July 20, 1860 in Despatches from United States Ministers to Great Britain, 1791-1906, Microcopy, FM 30, Roll 71. ↩

- George M. Dallas, diary entry, July 20, 1860 in Susan Dallas, ed., Diary of George Mifflin Dallas, While United States Minister to Russia, 1837 to 1839, and to England 1856 to 1861 (Philadelphia: J.P. Lippincott Company, 1892), 410. ↩

- Lewis Cass to George M. Dallas, No. 278, September 11, 1860. Diplomatic Instructions of the Department of State: Great Britain, July 20, 1860 to August 13, 1861, Microcopy, FM 77, Reel 75. ↩