Aaron Alpeoria Bradley and Black Power during Reconstruction

American historians have long traced the genesis of the Black Power movement to 1966. I would argue, however, that one strain of the movement began almost exactly a century before—in 1865—during early Reconstruction in the post-Civil War South. Radical black resistance to coercive labor contracts, the failure of land redistribution, and the persistence of white supremacy lays bare the bloodiness of the period. But it also demonstrates that Reconstruction was not destined to end as it did. For a few tumultuous years, possibilities for a more just, equitable future for African Americans abounded—before they were cut short by the prevalence of vigilante violence, an overzealous and racist criminal justice system, and the withdrawal of federal troops.

Using the radical Georgia politician Aaron Bradley as a lens to the era, it becomes clear that the very early years of Reconstruction birthed the first Black Power Movement. If Black Power is defined as a quest for black self-determination and self-sufficiency, advancing black interests and values, then Bradley was certainly an early purveyor of the system. Bradley was born enslaved on a large plantation in South Carolina, but escaped to Boston in the 1830s, eventually becoming one of the nation’s first black lawyers.

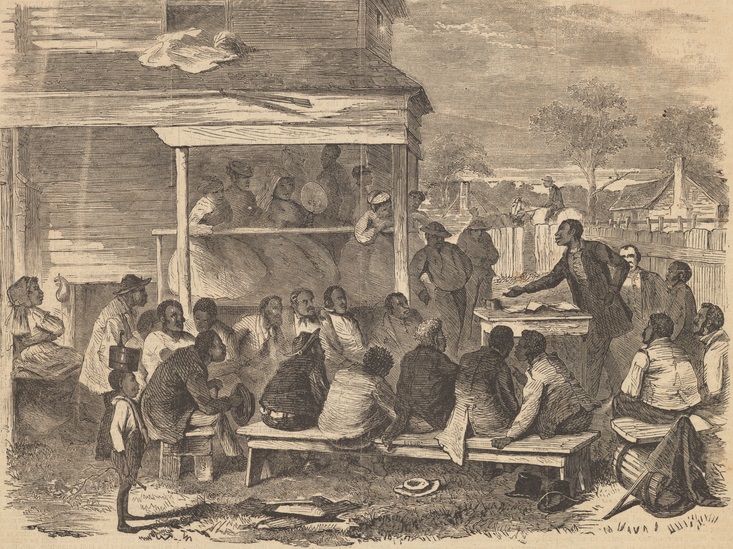

After the end of the Civil War, he moved to Georgia’s lowcountry, quickly becoming an important leader. Mere months after emancipation, Bradley allegedly demanded reparations in both cash and land. He urged freedmen to appropriate the crops they had produced, stay put on the land, and told them to refuse signing unfavorable labor contracts with whites. He was quite possibly the most arrested politician in all of nineteenth century American history. Through all his trials and tribulations, however, Bradley shrewdly backed his proposals with sound legal reasoning, and gained a faithful following of thousands.1

Aaron Bradley stood out wherever he went, as he was always dressed in flashy, fancy clothing, and usually donned a beaver-skinned hat and white kid gloves. He completed his look by surrounding himself with a throng of bodyguards. His appearance alone immediately attracted the ire of white southerners, but soon his actions would make him a marked man. Almost upon arrival into the South, Bradley began calling for the impeachment of President Johnson, pushing for land and labor rights for the freedmen, and accusing the local courts and police of overt racism.

As soon as Bradley began attracting a large following of freedmen, whites began trying to silence him. In late 1865 the occupying federal forces arrested Bradley for using “insurrectionary language in public assemblages, [and] inciting lawlessness and disturbance of public peace and good order.” Sentenced to a year of hard labor, the federals eventually allowed Bradley to leave the state instead. Yet soon he returned and immediately was elected to Georgia’s Constitutional Convention of 1867, where he championed civil and political rights for African Americans.

Foreshadowing the Populist movement by at least fifteen years by railing against “bankers, millionaires, merchants, aristocratic mulattoes, [and] copperheaded Yankees,” Bradley affirmed his place as the leader of lowcountry common black laborers. Despite his own mixed race heritage and middling class interests, he became the champion of the most oppressed and downtrodden.2

Bradley continued attacking capitalism and “gold coin,” and even banded together with poor whites over issues like the Homestead Acts, labor reform, and ending imprisonment for debt. Calling for an eight hour work day, he consistently tried to curb the power of corporations.

Increasingly he advocated armed resistance and at times encouraged blacks to employ violent means to achieve their end goals. Bradley even castigated white members of his own party for re-enslaving blacks by leasing convicts to railroad companies “who starve, whip and work and shoot them to death.” Indeed, he promised, “ere long the reign of police clubs and police authority would be abolished,” and “a blow” would be “struck which would stun even a policeman.”3

Indeed, given Bradley’s fiery language and open threats on the white power establishment, it is highly surprising that he was able to simply live—threats on his life were ubiquitous, and as he began breaking ranks with the Republican Party in the 1870s, they became even more numerous. Generally traveling with a band of bodyguards surrounding him, somehow he managed to avoid assassination.

Unfortunately, however, much of Bradley’s hard work would be in vain. By 1872, Georgia had been “Redeemed” as white Democrats retook the state. Effectively ending Reconstruction, this shift also signaled the end of Bradley’s official political career. Although he continued to hold mass meetings and create petitions, the next few years of his life would be lived in relative obscurity, as he moved back and forth from South Carolina to Georgia, trying to revive his legal career.

After nearly a decade of leading this valiant struggle for civil rights, continually thwarted at every turn, Bradley finally turned his hopes for black autonomy into dreams of black separatism. By the mid-1870s he was advocating colonization to Florida, and later he joined his interests with the exodusters to Kansas. Bradley finally made his own way to St. Louis, where he died penniless and alone in 1882.4

In 1966, almost exactly a century after Aaron Alpeoria Bradley began making waves in Savannah, the Black Panther Party put together a “Platform and Program” calling for many of the same civil, political, and economic rights that Bradley championed. Desiring self-sufficiency based on full employment, decent housing, and education, the Panthers—much like Bradley—held the system of capitalism responsible for much of the black community’s poverty and pain. Although their goals still have not been realized in today’s world, it is important to recognize their roots in early Reconstruction, at the hands of fearless freedom fighters like Aaron Bradley.

- Joseph P. Reidy in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed., Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era (Chicago: Illinois, 1982); E. Merton Coulter, “Aaron Alpeoria Bradley, Georgia Negro Politician During Reconstruction Times,” Parts 1-3, Georgia Historical Quarterly 51, Nos. 1-3, (March, June, and Sept. 1967); Savannah National Republican, Dec. 13, 1865, 2; John W. Blassingame, “Before the Ghetto: The Making of the Black Community in Savannah, Georgia, 1865-1880,” Journal of Social History 6, No. 4 (Summer 1973): 478. ↩

- Coulter, “Aaron Alpeoria Bradley,” Part 1, 18-9; 29; Daily Intelligencer (GA), Oct. 3, 1867, 2. ↩

- Southern Watchman, Feb. 19, 1868, 3; Coulter, “Aaron Alpeoria Bradley,” Part 2, 172; 171; 157; Savannah Daily News and Herald, Feb. 28, 1868, 3. ↩

- Savannah Morning News, Dec. 15, 1874, 3; Savannah Morning News, July 7, 1880, 3; Reidy, “Aaron A. Bradley,” 300; Weekly News and Advertiser, Oct. 28, 1882, 4. ↩

Genesis of Black Power in 1865? See “The Golden Age of Black Nationalism, 1850-1925” by Wilson Jeremiah Moses.

You are absolutely correct about earlier versions – that’s why I said “one strain of the movement.” Thank you for your comment, though – people should definitely know about Moses.

As always, another powerful piece by Keri Leigh Merritt. Until now, I had not read much about Aaron Alpeoria Bradley. He was certainly a great American hero. While his finals days were quite sad, it is refreshing to know that the fight for a just American society in which many of the socioeconomic barriers faced by African Americans today would be a thing of the past had its “roots in early Reconstruction, at the hands of fearless freedom fighters like Aaron Bradley.”

James Oloo

@JamesAlanOLOO

Thank you so much James! Your support is greatly appreciated. Keep up your important work!

Such a great piece! I first came across Bradley in Freedmen’s Bureau records where he advocated for the land holding rights of freepeople in the Sherman Reserve. The letters of Freedmen’s Bureau agents make it clear that he was a thorn in the side of officials in the Sherman Reserve who were attempting to strip freepeople of their land and return it to white landholders. For anyone who’s interested, the Freedmen and Southern Society Project’s volumes on Land and Labor have quite a few documents about Bradley. He’s a fascinating person. Great job, Keri Leigh!

Thanks so much Ashley! Still need to hit the archives later this summer but am working on a very rough article on Bradley – would love your comments when I finish!