A Womanist Perspective of the Black Power Movement

*This post is part of our online roundtable on Ashley Farmer’s Remaking Black Power

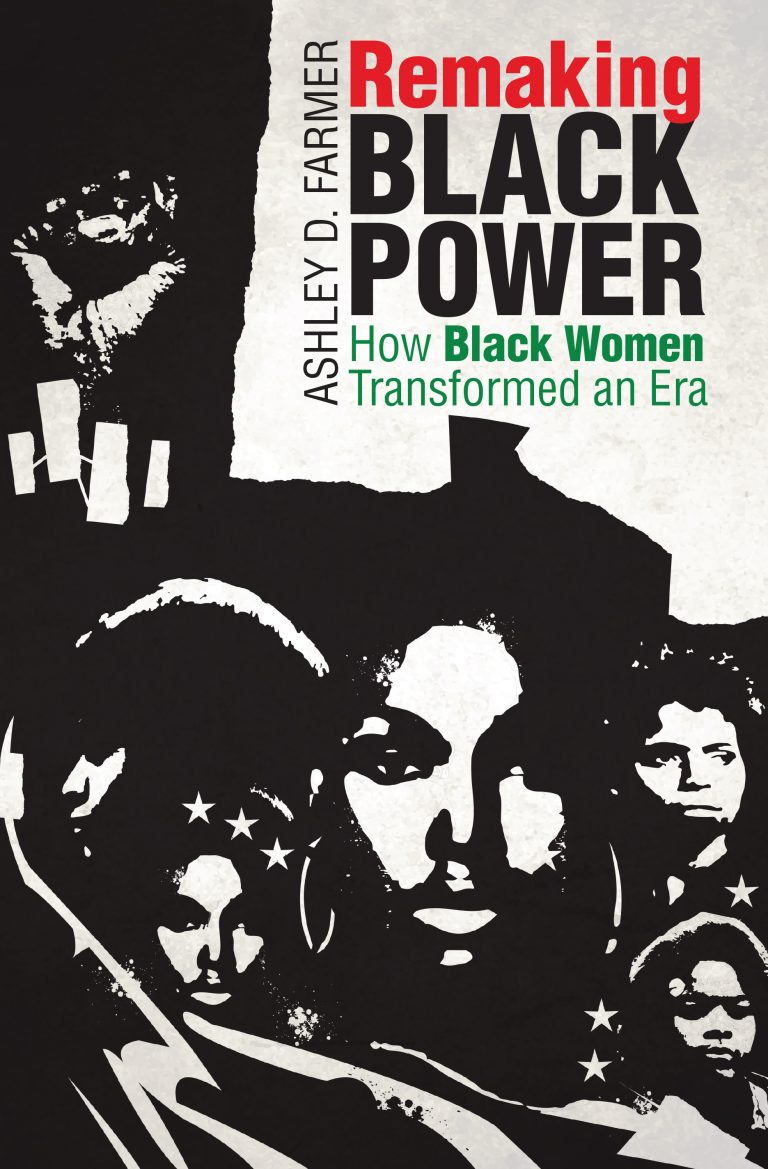

Ashley D. Farmer’s Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era represents an essential development in a new generation of Black Power scholarship. Farmer’s contribution is a woman-centered overview of the Black Power movement. Like Peniel Joseph’s work, Remaking Black Power will reinforce the significance of recognizing Black Power studies as a sub-field in African American history and Africana studies. Preceded by Rhonda Williams’s Concrete Demands: The Search for Black Power in the Twentieth Century and Robyn Spencer’s The Revolution has Come, Farmer’s Remaking Black Power continues a trend within Black Power scholarship that challenges masculinist narratives of the movement.

Remaking Black Power is cutting edge as it offers a comprehensive-womanist perspective of the Black Power movement. Farmer’s interpretation of various categories of women’s activism is unique and illuminating. From the “Militant Black Domestic” to “Revolutionary Black Woman,” “African/Afrikan Woman,” and “Third World Woman,” Farmer offers frameworks to explore the representation of activist women with a variety of ideological developments within Black Power. The “Militant Black Domestic” parallels the antecedents of the Black Power movement through grassroots civil rights and Old Left intersections with the Black freedom movement. The “Revolutionary Black Woman” highlights women’s engagement with the Black Panther Party (BPP) and self-described revolutionary nationalism. The focus of “African Woman” is in the cultural-nationalist ideological trend, specifically Kawaida, from the Organization Us to the Congress of African People. The “Afrikan Woman” is a variation of cultural nationalism to the development of Pan-Afrikan nationalism, which was a dominant ideological trend of the Black Power movement in the early 1970s.1 Finally, the “Third World Woman” examines the revolutionary intersectional development of the Black Women’s Alliance and the Third World Women’s Alliance.

Like other seminal works, Remaking Black Power has us anticipating and opening the way for new scholarship, particularly on gender, women, and Black Power. Farmer’s treatment of Mae Mallory is the most that we have received to date on this vital freedom fighter and the cause surrounding her and the other Monroe (North Carolina) defendants. The anticipated contribution of Paula Seniors (a child of the Monroe movement of the 1950s and 1960s), focusing on the militant revolutionary women of that North Carolina community, will help to complete our understanding of Mallory and other mothers of the armed self-defense movement.

I have also been anxious for a complete depiction of Ethel Azalea Johnson, another Monroe activist. Johnson was a principal contributor to Robert and Mabel Williams newsletter The Crusader and an advocate of armed self-defense in the late 1950s and early 1960s. She later provided political and ideological education to Max Stanford and the radical-nationalist Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) in Philadelphia in the infancy of the organization. Johnson and Mallory both embraced the Marxist-Leninist Worker’s World Party (WWP) in the 1960s, which played a significant role in support of the Monroe defendants and solidarity with the armed self-defense advocacy within the Black freedom struggle. While some dissidents of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), like Harry Haywood, supported Black armed self-defense, the CPUSA hierarchy seemed to be threatened by the militancy of Monroe and the nationalism of Williams.

Farmer contributes to the historiography of Queen Mother (Audley) Moore. We also anticipate more on this influential figure of the Black Power movement in Farmer’s and Erik McDuffie’s upcoming special issue of Palimpsest, which will focus on Queen Mother Moore. Moore must be considered a critical ideological influence in Black Power as she brought influences of the Black nationalism of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) together with the Old Left Marxism of the 1930s and 1940s CPUSA positions on the Black freedom movement. Moore’s advocacy for reparations and demand for self-determination and nationhood in the Black Belt South influenced the predecessors of the Black Power movement. She indeed was in conversation with nationalist forces in the “Black Mecca” of Harlem in the 1950s and 1960s, including with Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam in Harlem and Nana Oserjiman Adefumi of the Yoruba Temple. Moore and Adefumi were founders of the African Descendants National Independence Partition (ADNIP) Party in 1964, which called for reparations and a separate territory for Black people in North America.

Moore was also a collaborator with the brothers Gaidi and Imari Obadele (a.k.a. Milton and Richard Henry) in establishing the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Africa (PGRNA). The slain Black revolutionary nationalist Malcolm X was considered the messianic and iconic symbol of the PGRNA and the New African independence movement, as the early New African citizens labeled themselves “Malcolmites.” But no one individual had more of an influence on this Black nationalist movement than Queen Mother Moore. In earlier work, Farmer described Moore as “the ideological and organizational force” behind the Republic of New Africa (RNA). This is evident in Moore’s role in the March 1968 Black Government Conference organized by the Obadele brothers and their group, the Malcolm X Society. Moore proposed to name the envisioned independent Black nation, “New Africa.” She also was the first of 100 conference participants who signed a declaration of independence from the United States and was named an officer in the provisional government.

An in-depth study of the PGRNA and its women citizens is potentially another focus of the trend initiated by Black Power scholars like Williams, Spencer, and an extension of Farmer’s Remaking of Black Power. Queen Mother’s lieutenant, Virginia Collins, would become the southern regional vice president of the PGRNA. Collins would later become known as Dara Abubakari. She was the child of Garveyite parents and associated with Anne and Carl Braden’s Southern Conference Education Fund. Known as “Sister Dara” in the Black liberation movement, she would continue to be one of the key figures, along with Chokwe Lumumba, in the New African movement after the arrest and conviction of Imari Obadele and other PGRNA leaders in Mississippi. Under the military command of Boston-based Black nationalist Alajo Adegbalola, the PGRNA’s paramilitary formation, the New African Security Forces (NASF) trained and integrated women into its chain of command. Adegbolola’s daughter, Fulani (Sunni-Ali) was a respected soldier and NASF commander. The development of Rondee Gaines’s dissertation on the political activism of Fulani Sunni-Ali into a published manuscript will forward the experience of PGRNA women into the historiography of Black Power. Sunni-Ali emerged as a symbol of resistance during the post-Black Power period, as she was interned (incarcerated) for not cooperating with a federal grand jury investigating the Black Liberation Army in the early 1980s.

Spencer’s and Farmer’s womanist reconstruction of the BPP focuses on the faction of the BPP centered in Oakland and headed by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. Some of my previous research was based on the other side of the 1971 split of the BPP and the development of the Black underground or Black Liberation Army (BLA). One of the most well-known personalities associated with the BLA is Assata Shakur. She is mentioned early in Remaking Black Power.

Several women played significant roles in the Black underground. One story of an insurgent freedom fighter that intrigues me is Saundra Pratt (a.k.a. Nsondi jiJaga), a sex worker turned revolutionary and the late wife of Geronimo ji Jaga Pratt. She was eight-months pregnant when she was murdered in November of 1970, while Geronimo was awaiting trial in Los Angeles County Jail. In tribute to Nsondi (a.k.a. “Red”), Geronimo wrote: “High Commander of the Amazonian Army, My most faithful comrade in Arms, Symbol of the Black Guerilla Woman of the 21st Century….”

Another revolutionary female freedom fighter was Safiya Bukhari-Alston (formerly known as Bernice Jones), who tells her story with the assistance of white anti-imperialist revolutionary Laura Whitehorn, in the autobiography The War Before: The True Life Story of Becoming a Black Panther, Keeping the Faith in Prison, and Fighting for Those Left Behind (2010). Bukhari was head of Information and Communications for the “East Coast,” the pro-armed struggle wing of the BPP, who went underground in 1973 and was captured in an attempt to free BLA members from incarceration. She escaped but was captured again in 1975. She escaped again in 1976 and was recaptured in 1977 and finally paroled in 1983. Bukhari dedicated her activism to the amnesty and support for political prisoners and prisoners upon her release and co-founded the Jericho Movement for this work. While not in the BPP, former PGRNA worker Nehanda Abiodun is in exile in Cuba and is wanted in the United States on charges related to clandestine-revolutionary activity. Like Shakur, while “free” but living in asylum, Abiodun is separated from children and family.

The scholar-activist Sherie Randolph is currently doing work on the revolutionary Black women political exiles in Cuba, including Mabel Williams, Assata Shakur, and Nehanda Abiodun. As the current Black Lives Matter movement has adopted the quote from Assata Shakur as a first affirmation, we must remember the consequences and sacrifices made by these Black revolutionaries.2 We must also remember that both Shakur and Abiodun are on the Federal Bureau of Investigations’ “Most Wanted Terrorists” list. Therefore, Randolph’s work is so important and critical to our ongoing struggle for liberation and contemporary fight for freedom.

Ultimately, the work of Farmer and the publication of Remaking Black Power opens the way for her and other brilliant scholars to build upon this groundbreaking work. This book contributes to the scholarship of Ula Taylor, Barbara Bair, Natanya Duncan, Keisha N. Blain, Asia Leeds, and others as a collective intervention in the historiography of the Black freedom struggle to challenge the masculine-dominant and exclusive interpretations of Black nationalism in the United States and Pan-Africanism in the diaspora. We expect more interventions, as sisters have shaped our movement and our world.

- Russell Rickford’s We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power and Radical Imagination, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016) and Richard Benson’s Fighting for our Place in the Sun: Malcolm X and the Radicalization of the Black Student Movement, 1960-1973 (Bern: Peter Lang, 2014) give us some of the best reconstructions and interpretations of Pan-African nationalism in the 1970s. ↩

- The following quote from Assata Shakur is a major affirmation of the Black Lives Matter movement: “It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win. We must love each other and support each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains.” ↩

“We all thank you (Detroit, Michigan) for this historical powerful message”

thanks for reading!

Peace. I am looking for a photo of Queen Mother Moore and I am hoping one of you scholars can help me. It is of her and another Brooklyn activist from the EAST named Job Mashariki. The two of them are in Ghana at a crowning ceremony. This is a request from Mr. Mashariki. He believes the photo is in a book on Queen Mother Moore but does not know the name of the book. He’s sure the event was in 1971-2, though.

I do not see much on her specifically. I was hoping I could save time by “going straight to the source”. Does anyone know where I can find this photo?

I thank you in advance for any assistance you might be able to give me with this. I’m always good for a favor in return.

– E.J.

harlemcore@aol.com

have you looked through the following book: A View From the East:

https://books.google.com/books?id=lbvOF1BUT2oC&printsec=frontcover&dq=a+view+from+the+east&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjoreqK_dLaAhVR2qQKHUr2AKEQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=a%20view%20from%20the%20east&f=false

you might also try contacting this author.

Asante Sana,

Will share this article in our political education sessions, Baba Umoja.

FTL!