A Violent and Violating Archive: Black Life and the Slave Trade

This post is part of our online roundtable on Sowande’ Mustakeem’s Slavery at Sea

In Slavery at Sea, Sowande’ Mustakeem takes us on an intimate and harrowing journey through the Middle Passage. With an archive that defies our knowing the outcomes of the lives that survived the deadly crossing and sales in American ports, and a historiography (with important exceptions including Smallwood’s Saltwater Slavery) that tends towards replicating the numbers of captives bought, sold and perished, Mustakeem offers us an unflinching and up-close study of how African captives were “unmade” and then “manufactured” into slaves through their purchase, transport and resale throughout the Atlantic world.

Mustakeem begins with the procurement of captives in West African coastal towns and the complex negotiations and networks navigated by captains, sailors, African traders and elites to deconstruct African bodies in exchange for the desired commodities including arms, textiles, and alcohol and the conflicts that emerge through political shifts and local relationships. Mustakeem is purposeful throughout the book in centering the experiences of the captives confined on the coast and on board slave ships. She successfully demonstrates how market demand and exchange for black bodies created a terrorizing and violent environment for the people being bought and sold. In this process, with care and attention to women, the elderly and children, the author tells us of the assessments used to value bodies and illuminates how those “refused” for purchase met ultimately violent and traumatic ends on both sides of the Atlantic.

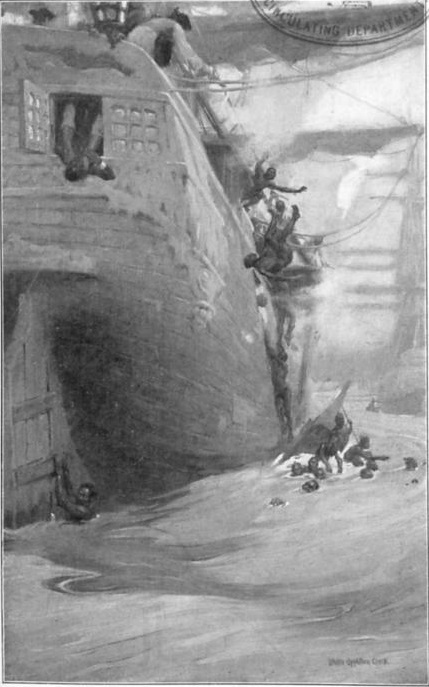

Mustakeem is keenly attentive to the everyday experiences on board slave ships and how captives-women and men, boys and girls-responded to the trauma of sea bound captivity. Several poignant moments arise in Mustakeem’s accounts of captives refusing to eat, descending into what the crew deemed “melancholia” or sullenness, and descriptions of the range of sexual dangers captive women faced in the confines of the ship—whether in secluded cabins or in plain sight. In these stories, the author casts the life, sounds, feelings and other sensorial and violent aspects of the Middle Passage in stark relief despite the absence of first hand captive accounts of their perspectives. And, here is one of the many strengths of the book—Mustakeem fights against the deafening silence and commodifying discourse of the European archive to give us glimpses of individual—if fleeting and traumatized, lives.

There has been a burgeoning of scholarship reconsidering the slave trade and slavery as productions of bodies, labor and wealth. These include the remarkable works of Walter Johnson (2013) who grapples the global reach of cotton markets, and Edward Baptist (2014) whose work focuses on the centrality of the slavery (including the domestic slave trade) to antebellum capitalist enterprises in the north and south and the energy and destruction of enslaved bodies necessary to sustain such markets. Sven Beckert and Seth Rockman’s edited volume Slavery’s Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development (2016) continues the discussion centering slavery and slave markets’ imbrication in, if not a constituent aspect of, capitalism. Most recently, scholars have revisited Cedric Robinson’s exemplary and foundational text Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1983) in the most current issue of the Boston Review (2017). Stephanie Smallwood’s essay in this issue centers the slave trade in the making of capitalism and—not as Marx would place it—“in capitalism’s prehistory of ‘primitive accumulation.’” These questions reorient our attention to the lingering legacies of black commodification and subjection and force an acknowledgement of how black bodies, labor and death produced markets, wealth and global networks for much of the West.

Yet, this critical work also points out how again, even with good intentions, a focus on markets and slavery can implicitly puts the lives of the enslaved in aggregated abstraction much like the contests over how many captives were transported that is characteristic of some of the early historical work on the transatlantic trade in human lives. Mustakeem’s book clearly challenges this tendency with her focus on the minute details of individual captives, the details of diseased bodies, and the intermittent stories of the enslaved in moments of resistance or facing death on different ships. As the scholarship on capitalism can sometimes serve to dissolve enslaved people into abstractions of markets, numbers, accumulation and wealth, Mustakeem brings us back to the living, breathing, moaning of captive’s shipboard lives and last moments.

I wonder though, as a scholar of slavery who has faced down a similarly violent and violating archive of battered and scarred bodies, what we should walk away with in recounting this violence and indexing of diseased, raped, beaten, mutilated, and frail black bodies? This question, of course, does not desire a swing to narratives of resistance and heroism. It is, rather, a question of how do we subvert the reproduction of the logic of this archive and the violence that seems to dominate it? And, how does this history shape the present precarity of black life?

The continued or reinvigorated interest in slavery and the slave trade is certainly not confined to the field of history or to the questions of capitalism’s origins. Many scholars have similar concerns with abstractions and the reproduction of archival violence while navigating through some of the same archives with which Mustakeem deftly contends. Laying out the stakes of working within the “mortuary of slavery’s archive,” a new special journal issue on “slavery and the archive” asks,“What is at stake in revisiting the devastation and death contained in the documents of slavery?” “Does this not subject the dead to new dangers and a second order of violence?” Inspired by Saidiya Hartman’s essay “Venus in Two Acts,” the special issue addresses the “ethics of historical representation.” In other words, what do we do with the violence in and of the records of the slave trade that leave African captives in states of disability, violation, and death? How are we to narrate their experiences beyond their inescapable and permanently violated archival representations? Are the stories of the Middle Passage we narrate from these archives about the recovered subject-hood of individuals we see just before they disappear or “rather about the violence, excess, mendacity, and reason that seized hold of their lives, transformed them into commodities and corpses, and identified them with names tossed off as insults and crass jokes?”

Mustakeem’s Slavery at Sea provokes these questions and forces us to revisit the terror of the slave trade and the traumatized lives of the captives forcibly taken across the Atlantic. And in our present moment, “What could be of greater critical and philosophical import than the matter of black life in a context of anticipated death, brutal violence, and enduring dispossession?” Mustakeem’s work offers a point of departure to think about how these legacies of racial terror and captivity continue to inform our present.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Excellent insights. Brilliant!

Dr. Mustakeem’s intellectual perfection of disclosing unspeakable and breathtaking tragedies of our History makes one quickly parallel our current day mental slavery with wide-open eyes…