A View From Within: Inside the Black Panther Party

This post is part of our online roundtable on Robyn Spencer’s The Revolution Has Come

Robyn Spencer’s The Revolution Has Come is a brilliantly balanced study on the Black Panther Party (BPP) in Oakland, California. Centering Black Power within a context of “deindustrialization, state violence, and global revolution,” the book offers a beautifully written, meticulously researched inside-account of the BPP. It aims to show readers what it was like to live inside the BPP through the experiences of its rank-and-file members.

It is notable that The Revolution Has Come focuses solely on the original Oakland branch of the BPP. Relatively recent scholarship on Black Power has been trending away from Oakland and toward discussing earlier Black Panther formations, including those beyond the United States. Through the lens of gender, The Revolution Has Come convincingly shows there is much more to learn about not only the men and women of the Oakland branch, but activism in Oakland in general.

In contrast to works like Joshua Bloom and Waldo Martin’s recent Black against Empire (2016), which avoided the use of personal testimonies as primary sources, The Revolution Has Come is constructed around twenty-five interviews Spencer conducted in 1997. In some ways, then, this project has been a labor of love at least twenty years in the making. While The Revolution Has Come is her first monograph, Spencer has long been respected as a scholar of Black Power and the BPP. Indeed, her decades of research, teaching, and expertise on Black Power and her personal engagement with former Panthers and community work, archives, and secondary sources on Black Power consistently speak through the pages of the text.

The Revolution Has Come begins with a discussion of Black activism in Oakland in the post-WWII era. Engaging the works of scholars such as Donna Murch and Robert Self, it shows how Black Power in Oakland was informed by Black southern migration to Oakland and issues surrounding urban renewal, segregation, and years of police brutality. The study moves through the Party’s formation, its development into a mass movement, its survival programs and electoral politics, and its challenges in dealing with COINTELPRO and political repression by the FBI. While all these topics are handled well, perhaps the book’s biggest contributions are its three chapters that span the Party’s branch activities in the 1970s, and, as Spencer frames it, the Party’s demise in the late 1970s–1980s.

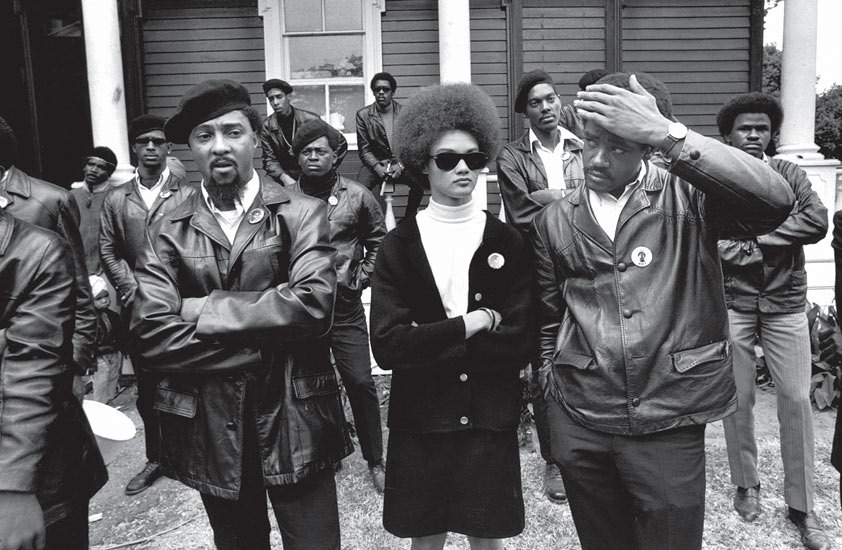

The Revolution Has Come adds to recent scholarship on the BPP in unique and refreshing ways. It illuminates many relatively unfamiliar grassroots Black activists, protest organizations (such as Mark Comfort and the Flatlands newspaper), and Panthers. Still, it is not just a narrative of the unknown. Familiar icons such as Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, Ericka Huggins, George Jackson, Elaine Browne, and Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver are featured throughout the text. Framed by the context of gender, the book explores how Panther women and men wrestled with several isms—classism, sexism, materialism, and individualism. Spencer makes it clear that the Panthers sought not to only change the world, but to personally change themselves—politically, socially, culturally, and economically.

While the text is very much a local narrative of Oakland’s BPP, it does briefly address the global influences on the BPP as well as its impact. For example, Spencer discusses how Seale and Newton framed the Party within the context of Marxist theory and Third World liberation and political theories of the likes of Frantz Fanon, Che Guevara, and Mao Tse-Tung. Spencer also argues that the BPP was an “effective ambassador” for Black Power outside the United States. It is interesting that Spencer uses the adjective “effective” to describe the BPP as ambassador, as opposed to words like iconic, dramatic, or even unrivaled, but this word choice speaks to Spencer’s writing style. She does what other scholars often find difficult to do—give a balanced assessment of the BPP that describes its challenges with state power, sexism, and personal issues without romanticizing or chastising the young men and women who ran the Party. The word “balanced” might seem like a substitute for the word “safe.” Indeed, given her extensive research, none of Spencer’s arguments seem to be “stretched.” However, it would be wrong to assert that the book does not have “bite.”

Just a few pages in to the book, Spencer begins to press buttons. She asks perhaps the most critical question for scholars of Black Power: “What does Black Power have to offer in the context of drone warfare, deepening poverty, unemployment, immigrant detention, and a criminal justice infrastructure that is an engine of destruction in black and brown communities?” Granted, the text does not exhaustively answer this query—this work is largely left to the reader. What it does, however, is link the Black Power Movement to the Black Lives Matter Movement and contemporary Black activism. This is a decided departure from other studies on Black Power that have sought to tether Black Power to a tradition of American democracy marked by the presidency of Barack Obama.

The Revolution Has Come is neither a “Black progress narrative,” nor is it solely academic. Spencer writes, “the study of Black Power doesn’t just fill holes in the scholarly literature; it fills holes in the tapestry of the American past. It fills bullet holes.” The question of the Panthers and bullet holes speaks to the physical, psychic, and political violence enacted on the Party by J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI, and COINTELPRO. Spencer succinctly deals with this period of political repression, revealing how it impacted women and rank-and-file members in the Party. It hurts to read how the American government used surveillance, extensive resources, and psychic warfare to attack party members—comrades, friends, lovers, sisters, and brothers. Some of these wounds are still open. Yet, it is also ironically helpful to be reminded of the lengths that the State will go to suppress voices of dissent.

The bullet holes that Spencer refers to are not just those launched at the BPP by the police in the 1960–1970s—or the bullet that fatally felled Newton in 1989. Spencer speaks to the police violence enacted on Black and Brown bodies today. For example, Spencer writes that “the Black Panther Party was born of the problems and potential of Oakland’s Flatlands,” a region that included East, West, and downtown Oakland as well as Fruitvale, a historic Mexican community. It is impossible to read this and not think of the tragic shooting and death of Oscar Grant at the Fruitvale Station in 2009.

As such, The Revolution Has Come is geared toward veteran and younger activists involved in contemporary movements against “police violence, mass incarceration, political prisoners, poverty, workers’ rights, justice in the Middle East, and intimate partner violence” (p. 204). There are important lessons to be learned in how the Party’s rank-and-file dealt with interpersonal conflicts, sexism, relationships, and family. It would be interesting to know the author’s views on how contemporary activists could use Black Power’s dealings with COINTELPRO as a lesson for Black activism in an era of social media, “selfie surveillance,” and online activism. All in all, for those interested in Black Power, the BPP, and Oakland, The Revolution Has Come should be one of the first books to reach for. However, for readers expecting to read Spencer’s take on Angela Davis—who is conspicuously absent from the text—they will have to wait for her next project, which will focus on Davis.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Looking forward to this publication. Quito Swan’s Black Power in Bermuda: The Struggle For Decolonization is also a must read!