A Tool for Our Times: Legacies of Black Radicalism and Communism

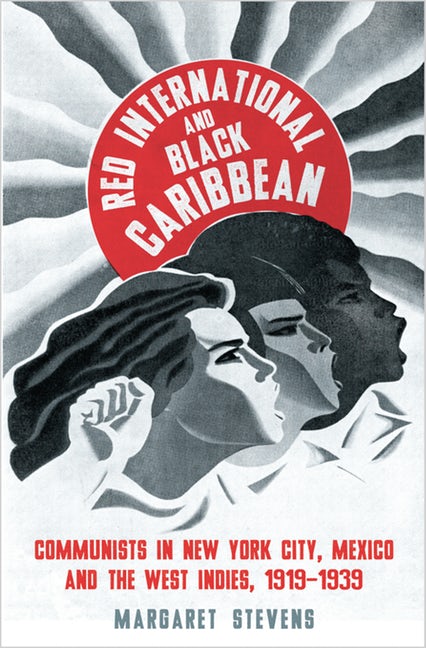

Speaking recently about “Mapping Communist Internationalism and Class Struggle Then and Now” at the social movement incubator that is The People’s Forum, historian Margaret Stevens spoke directly about the utility of her recently-published book. Red International and Black Caribbean, Stevens told her audience, was written not only to unearth an historical record overlooked, but also for purposes of praxis. Her book succeeds on both counts, speaking as it does to the interwar scene while prompting us to connect the politics of that period to the demands of the present.

Subtitled “Communists in New York City, Mexico and the West Indies, 1919-1939,” Red International chronicles the importance of Communist organizations to freedom struggles of the twenties and thirties, and the centrality of Black workers to those organizations across a geographic expanse that encompasses Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, the British West Indies, Mexico, and New York, with the Soviet Union sitting somewhere just off stage. Arriving amid a growing and dynamic list of titles that bring Black studies into conversation with Soviet cultural studies, Red International advances four principal arguments: it places Black workers at the center of the Black radical tradition, it emphasizes the importance of the Black Caribbean to the international Communist movement, it posits a non-dichotomous relationship between Garveyism and Communism, and it opposes anticommunism in evaluating Communism’s inconsistencies from the perspective of collective subalternity.

To cover this much geographical, temporal, and conceptual ground within one volume, a systematic structure of argument is imperative. And here again Red International does not disappoint. Divided into three parts comprised of two or three chapters each, the narrative moves methodically from place to place and in chronological sequence. Following an effective introduction that lays out the book’s main claims, “Bolshevism in Caribbean Context” introduces a range of militant groups and publications, documents the development of Leninism in Mexico, and vividly recounts how, as US capitalism stopped roaring and slid into depression, Communists and their comrades rallied on the streets of New York in solidarity with a student-led “Haitian Revolution” against Haiti’s ongoing occupation. The book’s second section, “Two Steps Forward,” turns to the Scottsboro case in transnational context before exploring organizing efforts in Cuba and the Anglophone Caribbean. Finally, “Race, Nation and the Uneven Development of the Popular Front” considers Black Caribbean responses to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, debates over the strategic wisdom of left-liberal collaboration, and ultimately, the horrifying outcome of anti-Black racism along the Haitian-Dominican border. All the while, Stevens keeps the evolving priorities of the Comintern in view.

This book makes a long list of contributions, not least being the advancement of our knowledge about the significance of Garveyism, the Soviet role within the Communist movement, and the contradictions of the Popular Front. In contrast to the literature on Communist Black radicalism that has at times neglected Black nationalism, but in keeping with recent scholarship that has demonstrated Black nationalist continuity and Black Communist and nationalist political overlap, Stevens shows how Communism and Garveyism remained related – if in a relationship best characterized as one of affinity and rivalry – throughout the interwar years. Meanwhile, on the issue of Soviet control within international Communism, itself a subject of longstanding debate as well as masterly analysis within Black studies, Red International’s attention to the painstaking details of evolving politics across the Black Caribbean makes compelling the case that multiple sites of leadership generated strategies for emancipation from racial capitalism. “The history of the Communist International,” Stevens contends, “must be understood as a global process in which colonized regions and semi-colonized nations like Haiti, where black workers were the dominant majority, both impacted revolutionary strategy coming from Moscow and, in turn, were affected by decisions from the Communist global headquarters.” And yet however much Black workers were able to shape Moscow’s given line, as Stevens shows in the case of the Popular Front, its adoption sometimes came at a terrible cost.

This book makes a long list of contributions, not least being the advancement of our knowledge about the significance of Garveyism, the Soviet role within the Communist movement, and the contradictions of the Popular Front. In contrast to the literature on Communist Black radicalism that has at times neglected Black nationalism, but in keeping with recent scholarship that has demonstrated Black nationalist continuity and Black Communist and nationalist political overlap, Stevens shows how Communism and Garveyism remained related – if in a relationship best characterized as one of affinity and rivalry – throughout the interwar years. Meanwhile, on the issue of Soviet control within international Communism, itself a subject of longstanding debate as well as masterly analysis within Black studies, Red International’s attention to the painstaking details of evolving politics across the Black Caribbean makes compelling the case that multiple sites of leadership generated strategies for emancipation from racial capitalism. “The history of the Communist International,” Stevens contends, “must be understood as a global process in which colonized regions and semi-colonized nations like Haiti, where black workers were the dominant majority, both impacted revolutionary strategy coming from Moscow and, in turn, were affected by decisions from the Communist global headquarters.” And yet however much Black workers were able to shape Moscow’s given line, as Stevens shows in the case of the Popular Front, its adoption sometimes came at a terrible cost.

Made official in 1935, the Popular Front position called for non-sectarian alliance against fascism. While logical on its face, especially given then-recent events in Germany, the Popular Front also meant quieting critiques of state repression, capitalist exploitation, and racial oppression. The Popular Front position focused Communist minds on Nazism’s consolidation and the march of Franco’s fascists in Spain. But unlike the support for the “Haitian Revolution” of 1929, the deportation of Black workers from Cuba and the massacre of thousands of Haitians in the Dominican Republic in 1937 was met with relative acquiescence in many Communist circles. Stevens concludes her study with this event, replete as it is with “lessons for what not to repeat in the years to come.”

Red International has something to teach us about Garveyism, Soviet-centered Communism, and the Popular Front, among other things, because of the gripping and multilayered story it tells, but also because of that story’s foundation in deep research. Stevens has delved into the archival collections of individuals and into organizational records, most notably the voluminous papers of the Communist Party of the United States at the Library of Congress. But being an intellectual as well as an organizational movement history, this book also provides a fascinating reading of numerous radical periodicals, from the Crusader and the Daily Worker to the Negro Champion and New Masses.

Red International, however, does not feature a similarly extensive engagement with the secondary literature on the subjects it explores. Instead of becoming bogged down in all manner of scholarly debates, Stevens boldly eschews citations in her introduction, and dispenses with a conclusion, which has the effect of streamlining her account and showcasing the primary-source material on which her interpretation relies. I wonder, though, what might have been gained had Stevens put this book in more direct dialogue with the literatures that clearly inform her thinking. What if Red International had devoted more space to comparing its interpretation to Christina Heatherton’s incisive scholarship on the Mexican Revolution’s impact on radicalism in the United States, or Minkah Makalani’s influential study of interwar Black internationalism? Or Hakim Adi’s examination of the Communism of interwar Pan-Africanism, or Cheryl Higashida, Dayo Gore, and Erik McDuffie’s accounts of the feminist dimension of Black radicalism and Communism’s co-constitution? Or, for that matter, S. Ani Mukherji’s astute analysis of Black cultural work or Wendy Goldman’s searing portrait of Stalinist purges within the interwar Soviet Union? Would such engagements have been worth the potential encumbrance? I’m not sure what the answers are to these questions, but they seem worth considering as we read and grapple with this book.

Much easier to answer is the question as to whether Red International relates new research while speaking to today’s political predicaments. Does a grounded historical account of liberation struggle and fraught coalition resonate when imperialism continues to beset the Caribbean, when across the globe open white supremacy is again on the rise, fascism is emergent, misogyny prevalent, capitalism dominant, and many of us looking for better ways to contest all of the above? As with other key works on Black radicalism and Communism, Red International’s lessons for the present are readily apparent.

While working my way through this work of history that’s also a tool for our times, I took a photograph of it, as I’ve fallen into the habit of doing with books I’m reading. In the background is a revolutionary sailors’ memorial in Rostock, Germany, where I currently live. Created during the days of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and at the moment enduring a construction-fencing encirclement, the site’s statue stands as an illustration of the kind of socialist realism that Kirsten Ghodsee has written so affectingly about. Rostock of the GDR is a long way, in many ways, from the interwar Black Caribbean world that Red International calls to our attention. And yet they’re also connected in that wherever it appeared, Soviet-centered Communism – while legitimating regimes that fell far short of the freedom they promised – officially celebrated everyday people, fought fascism, and challenged racial capitalism.

Red International is more relevant for today, however, than a statue that happens to be in the same town as this reviewer. This book shows how historical actors answered questions that remain fiercely urgent now, as those actors theorized the relationship between antiracism and anticapitalism in pursuit of dreams of freedom. Thanks to the archival work and storytelling power Margaret Stevens brings to bear in Red International and Black Caribbean, the lessons of those organizers, theorists, and dreamers are there for us to ponder and to learn from.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for this wonderful review. I am curious how this work may or may not been have been in conversation with Winston James’s Holding Aloft The Banner of Ethiopia? Obviously this work is broader geographically, but I am curious to know if Stevens grappled with Caribbean difference in terms of the various ways in which Black workers and activist-intellectuals organized from Mexico, to Cuba, Jamaica and and beyond? What are we to make of new narratives that fail to engage existing scholarship in the field? Is this still important or do densely-researched archival projects justify their own merit and sit above the fray? Again, thank you for this thoughtful review. I will be purchasing the book for sure.

Thanks so much for the generous and generative reply. To my recollection, Red International does not directly take up the arguments of Holding Aloft. I agree that Winston James’s book is very important both on its own terms and as essential background for this newer work. But as Margaret Stevens speaks about directly in her People’s Forum talk (one reason I opened with it, but also see if you haven’t yet this excellent interview I liked to later in the review: https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3929-labor-and-liberation-an-interview-with-margaret-stevens), a central purpose of this book is to provide a tool with which to reflect on a relatively marginalized history in service of thinking about the politics of the present, especially given the current urgency of forming an antifascist front. At first, I was disoriented by the extent to which Red International prioritizes primary sources over the work of other scholars (some of which is cited in the endnotes), but as I reflected on this more and came to see more clearly through her discussions about the book (at least in my reading of them) what Prof. Stevens was attempting to accomplish, her book’s utility and success came through all the more strongly for me. But still, I am left not quite able to answer the questions you so nicely pose about the relationship between new narratives and existing scholarship. Thanks again for giving me more to think about, and glad to hear that you plan to pick up a copy of this valuable book!