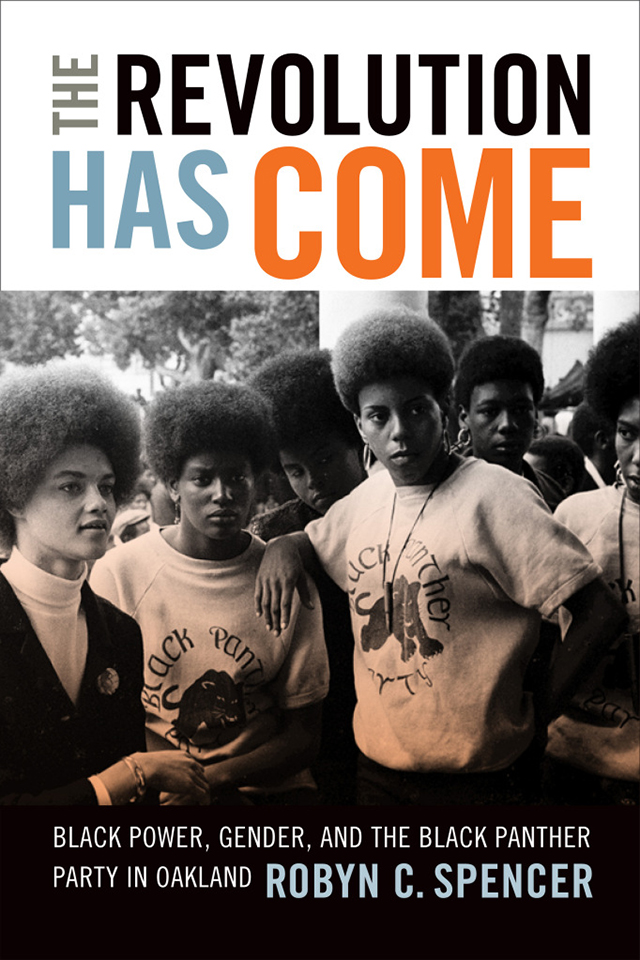

A New Take On An Old Story: Robyn C. Spencer’s The Revolution Has Come

This post is part of our online roundtable on Robyn Spencer’s The Revolution Has Come

The wealth of scholarly inquiry into the history of the Black Panther Party (BPP), including the most recent studies timed to accompany the fiftieth anniversary of the organization’s founding, still leaves many questions about the Party’s structure, accomplishments, and demise. One could read numerous books about the Panthers and learn precious little about the BPP’s daily activities, its finances, and why it fell apart.

Thankfully, Robyn C. Spencer’s excellent The Revolution Has Come sheds light on these issues. The author’s crisp, clean, incisive prose proved an eye-opening reading experience that at times left me dumbfounded as to how many myths and assumptions have come to dominate latter-day perceptions of the Panthers. The Revolution Has Come is no hagiography, but it will leave some people profoundly disappointed with certain key Panther figures, most notably Huey P. Newton, who in Spencer’s telling was more useful to the organization while incarcerated than while running things.

Other broadsides against Newton, like Hugh Pearson’s The Shadow of the Panther, might be cast aside as weakly sourced, biased, or part of a larger ideological takedown of the Black Panther Party. Spencer’s strongly researched and evenhanded approach will be harder for Newton—and BPP—apologists to contend with. Spencer’s account also states quite clearly that although Newton faced surveillance and harassment, it was neither police nor government repression that most profoundly compromised Newton, but rather his own failings.

The same point holds true for the BPP as a whole, Spencer argues, and not without faint traces of disappointment registering in a text wiped mostly clean of sentimental longing about the party or its members. The truly heroic of the Panther rank-and-file—mostly women—were betrayed catastrophically by party leadership—mostly men, especially Newton, and in a lesser sense David Hilliard. Although this is a less-than-flattering portrayal of Hilliard, The Revolution Has Come never ignores his contributions, particularly as the party chief of staff who played a crucial role in structuring the organization. Bobby Seale, on the other hand, comes off throughout as a reasonable leader, but Spencer nevertheless makes clear that women galvanized the BPP and that Panther men, especially at the top, were as likely as not to be detrimental to the group’s survival, including its ability to institute successful community programs.

What makes Spencer’s more critical portraits so convincing is that they are presented within an analytical structure that clearly articulates the BPP’s positive virtues as standard bearers of America’s civil and human rights vanguard. Readers of The Revolution Has Come will be greatly impressed by the reach of the BPP’s community programs and the dedication of its members. Overall it is a positive portrayal of the Black Panther Party that simply refuses to deny the organization’s many weaknesses.

The book’s economical length, just over 200 pages, testifies to Spencer’s ability to pick the right combination of words to relay complex ideas, often as signposts that keep the reader on course for her main points, as demonstrated in her description of Newton’s release from prison: “His release put the flesh-and-blood man on a collision course with the symbolic leader that Panthers had so carefully constructed” (96). The final narrative paragraph, just prior to the conclusion, perhaps best exemplifies Spencer’s ability to boil down ideas, as in merely a few sentences she succinctly summarizes one of her most important arguments:

The centralization of authority and the inability of rank-and-file members to hold leadership accountable severely circumscribed democracy in the Black Panther Party. The organization that had managed to empower black men and women to challenge so many institutions and fight for structural change in the world had disempowered them from believing that they could take the reins from one of their own party’s founders. Because criticism was unwelcome or resulted in only small reforms rather than a change of course, departure became the only recourse for disaffected members. In the end Newton would be the only Panther left standing in the wreckage.” (201)

Despite being one of the shortest books published about the Panthers, The Revolution Has Come is also one of the best.

Spencer’s skill as an oral historian rests at the heart of the narrative. While I am not an expert on the BPP literature, many of the names in this book were new to me and will be new to readers, too. Not only did Spencer track down forgotten Panthers, but readers will also note her ability to get subjects to recount difficult situations, uplifting stories, and revealing details about their, or other people’s, personal lives. Readers will feel the pain and the triumph of the Panther experience as its survivors tell their stories.

Another strength that typifies the book, and which is also evident in the endnotes (which are as orderly as such can be), is the author’s ability to locate a key data point or piece of evidence in an archive or interview and write a succinct, no-frills, useful paragraph about it. Want to know what happened to Panthers whose chapters closed but still wanted to be part of the movement? See page 116. Want to know where there was interest in forming new Panther chapters in 1971–1972? See page 114. Want a list of BPP survival programs provided through the United Black Fund as of October 3, 1972? See page 131. Time and again, the author carefully chooses detail, telling us what we really need to know, not more nor less.

Such detail, clearly rendered, serves an important function. Merely listing the range of BPP programs in Oakland gives the reader a sense of the organization’s impact as a community force: the Free Breakfast Program, the People’s Free Food Program, the Inter-Communal Youth Institute, the Legal Aid Educational Program, the Free Busing to Prisons Program, the People’s Free Shoe Program, the People’s Free Clothing Program, the People’s Free Medical Research Health Clinic, the People’s Sickle Cell Anemia Research Foundation, the People’s Free Ambulance Service, the People’s Free Dental Program, the People’s Free Optometry Program, the People’s Free Plumbing and Maintenance Program, and the Community Cooperative Housing Program.

My positive impression of The Revolution Has Come makes it difficult to render much criticism, but it would be interesting to hear Spencer further explain her relationship to the interview subjects and the process of interpreting their responses. Occasionally, a phrase in the book made me think she should have asked more questions. For example, she writes, “Darron Perkins’s story is instructive. Perkins, who had once endured five lashes with a bullwhip without flinching when he was brought up in front of the Board of Corrections, believed that physical punishment was a viable method of maintaining ‘iron discipline’ to deal with the ‘hardheaded’” (162). How did she verify whether the man flinched or under what circumstances he was whipped? What does it mean to be brought up in front of the Board of Corrections, and how did whipping become part of the procedure? Some information is missing here.

While this was the rare passage that lacked clarity, perhaps the harder critique of the book might be that the interviewees were generally portrayed positively. Accusations of bias, unconscious or otherwise, cut deep, but at times I wondered whether two of the book’s most critiqued figures, Newton and Hilliard, might have fared better had they been able (in Newton’s case) or willing (in Hilliard’s case) to tell their stories to the author. Was Spencer’s positive portrayal of Seale related to her interviewing him?

Certainly there were openings in the book for more critical language toward Seale. Spencer writes of the Attica prison uprising in 1971, “At the request of the prisoners Seale went to Attica to negotiate for them” (115). Heather Ann Thompson’s 2016 book Blood in the Water portrays Seale’s appearance at Attica as ineffective, if not detrimental; he refused to speak for or to the prisoners, many of whom would have liked him to do both. While the prisoners’ request reflects the great esteem and influence that Seale and the BPP had in the hearts and minds of many underrepresented people, his failure to come through at this big moment does not register in Spencer’s language, even though it was the perhaps the most crucial lesson to be learned from Seale’s Attica fiasco.

Despite these minor criticisms, The Revolution Has Come is a very strong book that I would recommend for high school, undergraduate, and graduate school students as well as general readers. Even seasoned experts on the BPP will likely learn much from this wonderful new account.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.