A Discourse on Race and Inequality in the United States

This post is part of our online forum on Race, Property, and Economic History.

The U.S. Census Bureau reported in early September (2017) that the median household income in the United States, in 2016, had gone up 3.2 percentage points since the year before, and had reached its highest ever level of $59,039. The increase, no matter how lauded, was so infinitesimal that it didn’t make any dent at all in the degree of inequality in the country. The Gini Index of income inequality hovered around .481 in 2016, not statistically different at all from that of 2015.

Even though the median income for Black households had gone up by a significant 5.7 percentage points, from $37,681 to $40,065, compared to only 2 percent for white households, it was still significantly lower than the median income of whites ($65,041), Asians ($81,431) and Hispanics ($47,675). Only American Indians and Alaskan Natives were making slightly less at $39,719.

Furthermore, a closer look at the numbers shows a deeper reality—59.6 percent of all Black households were making less than $50,000 in 2016; 33 percent were making less than $25,000. By comparison, 18.7 percent of white households were making less than $25,000. These numbers haven’t budged in more than a decade. According to the Census Bureau, 22 percent of African Americans, 9.2 million people, continue to experience entrenched poverty.

In a country where the distribution of wealth is even more skewed than that of income, the phenomenal wealth gap between Black households and their white counterparts is a profound testimony to the depth of their overall economic disadvantage. When financial wealth—stocks, bonds, real estate, and business investments are considered, the median net worth of white households is 13 times more than that of Black households—$134,230 compared to $11,030. Findings of a new study on racial wealth gap done by the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) and Corporation for Enterprise Development (CFED) released in 2016 shows that in the thirty year period between 1983 and 2013, average wealth of white families grew 84 percent—three times the rate of growth for Black families. At this rate, it will take 228 years for Black families to amass the same amount of wealth white families have today.

The report also noted that in the same period the wealth of the Forbes 400 richest Americans grew by an average of 736 percent.

Renowned French economist and author of Capital In the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty, in his analysis of the nature and sources of inequality in the United States today has found that it is primarily embedded in the extraordinary returns on capital assets such as real estate, financial holdings, and investments, which the richest of the rich disproportionately own. Though almost 52 percent of Americans owned stocks in 2016 the value was far less ($40,000) than what the top 10 percent owned ($365,000) in their stock ownership.

It is due in most part to the extraordinary returns on their net worth, their wealth, specifically capital assets, that the richest of the rich are pulling farther and farther away, not only from the rest of the society, but also from the merely rich,. So that individuals who simply live on a monthly salary, regardless of how high it is, will never match what the richest of the rich—the proverbial top 1 percent—earn through rents, interests and dividends from their capital assets.

As the income disparities become entrenched and passed down from one generation to the next, it creates a “hereditary aristocracy of dynastic wealth” which is almost exclusively white! As capital becomes concentrated in the hands of fewer people, political power and political decision-making becomes lopsided. Democracy gives way to oligarchy, enabling a handful to protect the mechanisms that maintain and enhance their economic and racial superiority. Moreover, control over massive wealth gives the super rich the ability to control the media to their own advantage, and manipulate the messages and images that people hear and see.

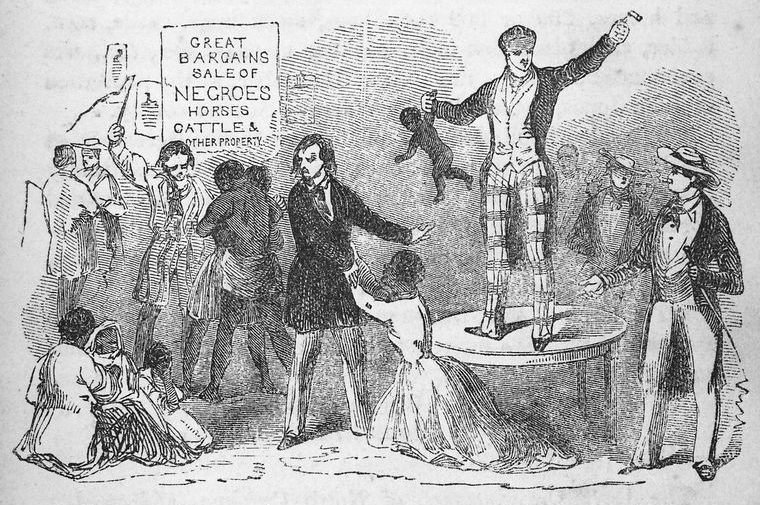

This might be the right time to ask the question, who creates the wealth of nations? We know who owns, but who creates? Of course, the wealth of nations is created by the working class of any society. The expropriated surplus value fuels capitalist accumulation and its continuous growth. All wealth in society is ultimately stolen property, endorsed and protected by the government, ultimately beholden to capital. Here, I would like to focus on the stolen labor of slaves, and the land of American Indians that created the seed capital of this land.

There are quite distinct historical processes that have created the wealth of some nations and the poverty of others; the enormous riches of some groups and the destitution of others. The intense inequality and adversity that we see today among African Americans and Native Americans have clear and undeniable historical antecedents. Colonial plunder, slavery, de jure discrimination, institutionalized racism in education and in the housing market, de facto discrimination in the work place—and the relentless violence which has been present every step of the way—have created entrenched, stubborn poverty and its staggering challenges.

There is a tremendous irony here, since these are the processes that were deliberately put in place to create the wealth of the colonial United States. Historians increasingly agree that the enslaved Africans worked on plantations carved out from lands cultivated by hundreds of generations of American Indians. These sacrifices produced the capital that was critical for the industrialization and economic development of the young nation. Economic historians compare the significance of cotton to the economy of the nineteenth century, to oil in our time. United States was the Saudi Arabia of cotton. Cotton was the most valuable export commodity that the United States produced. Twenty years before the Civil War, cotton made up 63 percent of the total value of exports. It connected the plantation economy to the Northern banking industry, ship building industry, insurance companies, investment houses, the textile factories in New England and Great Britain. And as Craig S. Wilder documents, some of the most revered universities—Brown, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Rutgers, Georgetown and many more—“were soaked in the sweat, tears and often blood” of slaves and Native Americans.

The legacy of historical racism created the bulwark of segregation—which continues to divide all Americans. More than fifty years after major civil rights legislation was enacted segregation remains stubbornly embedded in the social fabric of the country creating two nations separated by growing inequality, distrust and wariness.

Deindustrialization pulled the rug from under the communities of color. Between 1910 and 1979, almost half of all African Americans were working in industries. Segregation and racism were utterly suffocating, but as more Black men and women found work, it brought greater economic stability to their lives.

The instability and volatility that characterize so many of the inner city communities today directly follows from the structural changes in the economy that caused the disappearance of these industrial jobs that supported the African American work force. As work disappeared, and incomes hit bottom supermarkets, banks, department stores, restaurants, movie halls, doctor’ offices started moving away. What was left behind in the ‘devalorized’ communities were liquor stores, pawn shops, pay day loans, bail bonds and a few fast food places. In the absence of real jobs, public assistance and the underground economy based on what Sudhir Venkatesh calls “outlaw capitalism” took root.

How has the country responded? Instead of serious public policy to build and strengthen schools, investments in public work projects to boost employment, providing loans for small businesses, job training, job placement, quality day care, transportation, affordable housing, investments in building and repairing infrastructure, bolstering the social safety net—the United States has spent over $1 trillion in its three-decade long war on drugs. The response to a humanitarian crisis has often just been to build more prisons. The demonization of young Black men allows the criminal justice system either to lock them up or kill them—with impunity. And “as things fall apart and the center cannot hold and mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,” how might the narrative change?

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.