A Case for Reparations at the University of Chicago

Julia Leakes yearned to be reunited with her family. In 1853, her two sisters showed up for sale along with her thirteen nieces and nephews in Lawrence County, Mississippi. Julia used all the political capital an enslaved woman could muster to negotiate the sale of her loved ones to her owner, Stephen A. Douglas. Douglas’s semi-literate white plantation manager told him “[y]our negros begs for you to b[u]y them.” Despite assurances that this would “be a good arrangement,” Douglas refused to shuffle any of his 140+ slaves to reunite this separated slave family. Instead, Julia’s siblings, nieces, and nephews were put on the auction block where they vanished from the historical record.1

Unfortunately, things went from bad to worse for Julia. By 1859, she had a 1 in 3 chance of being worked to death under Douglas’s new overseer in Washington County, Mississippi. Douglas’s mistreatment of his slaves became notorious. According to one report, slaves on the Douglas plantation were kept “not half fed and clothed.”2 In another, Dr. Dan Brainard from Rush Medical College stated that Douglas’s slaves were subjected to “inhuman and disgraceful treatment” deemed so abhorrent that even other slaveholders in Mississippi branded Douglas “a disgrace to all slave-holders and the system that they support.”3

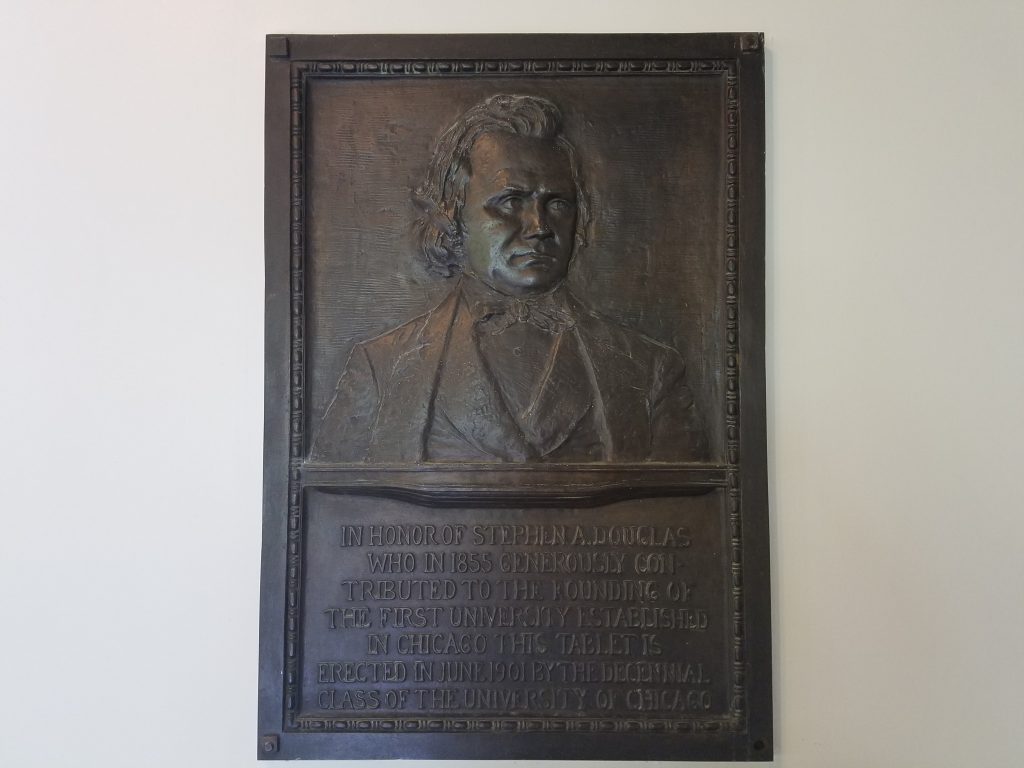

The University of Chicago does not exist apart from Julia Leakes and the suffering of her family—it exists because of them. Between 1848 and 1857, the labor and capital that Douglas extracted from his slaves catapulted his political career and his personal fortune. Slavery soon provided him with the financial security and economic power to donate ten acres of land (valued at over $1.2 million in today’s dollars) to start the University of Chicago in 1857. This founding endowment, drenched in the blood of enslaved African Americans, was leveraged by the University of Chicago to borrow more than $6 million dollars in today’s terms to build its Gothic campus, its institutional structures, its organizational framework, its vast donor network, and an additional $4 million endowment before 1881. In short, the University of Chicago owes it entire presence to its past with slavery.

When we began this project, we assumed that the University of Chicago was a postemancipation institution. However, as the University of Chicago historian and Dean of its College John Boyer has shown, the deep ties between the university’s original Bronzeville campus and its current Hyde Park campus constitute a rich “inheritance” and give the university what he calls “a plausible genealogy as a pre-Civil War institution.” Continuities between the two campuses can be found almost everywhere among its trustees, faculty members, student alumni, donor networks, intellectual culture, institutional memory, distinctive architecture, library books, and, of course, the University of Chicago’s name itself. The two campuses would undoubtedly be deemed inseparable alter egos of one another. Boyer convincingly makes this case. What he seems to have missed, however, was that this pre-Civil War founding also came with a founding slaveholder who endures to this day—haunting the halls of the Hutchinson Commons.

Due in no small part to the pioneering work of the Brown University Committee of Slavery and Justice and historian Craig Steven Wilder, we now know that the University of Chicago is not alone. Many elite colleges and universities have deep roots in American slavery. Many also owe their large endowments to the financial legacy of the slave economy. These schools continue to leverage these endowments to develop and recruit talented faculty and students, build up the physical plant, and maintain their global reputations in the marketplace of ideas. Once a school comes to grips with its historical ties to chattel slavery, however, what is its next step?

Many may argue that Georgetown University might provide a useful but incomplete starting point for the University of Chicago. Both schools are located in urban environments with a large African American population. Both are endowed with lots of money. Under the aegis of the Georgetown Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation committee, Georgetown has also publicly wrestled with the question of what it owes the descendants of the enslaved. Georgetown has decided that there is not a statute of limitations on slavery, and that to reckon with the past they had to engage historically. The university opened up four tenure track lines in African American Studies, expanded the African American Studies Major, and has plans to establish a Research Center for Racial Justice. In addition to these measures, the university will offer the descendants of enslaved African Americans sold by its friars preferential treatment in admissions (similar to the boost that so-called legacy students already receive). It will also rename two campus buildings in honor of African Americans—one an educator and another one of the enslaved who made the university a financial possibility. But is this enough?

Perhaps, instead, the University of Chicago can find a way to look beyond Georgetown and what many have rightly criticized as its self-congratulatory, self-serving, and extremely limited program. Given the University of Chicago’s location on the city’s South Side it is uniquely situated to engage and address the legacy of slavery in a much different way. Chicago, like Washington D.C., has long been one of the meccas of Black life and culture. Establishing an African American Studies department should be a no-brainer. So, too, should be a concerted effort to recruit and develop faculty of color while vigorously recruiting and mentoring underrepresented students to attend the university. But this should happen anyway. It’s not reparations.

Maybe a further step would be to encourage the University to build more deeply upon the community-based efforts it is already engaging in. These include the UChicago Promise program, which provides enrichment programs for talented but under-served public school students. There is also the Chicago Public Schools Educators Award Scholarship—a full scholarship to attend the University for the children of educators in the Chicago Public Schools—which should be broadly promoted and expanded. The University’s Arts + Public Life programming, including the Washington Park Arts Block, the Black Cinema House, and the Stony Island Arts Bank (led by the indefatigable Theaster Gates) should all continue to invite local residents to engage in their programming. But, again, this is already happening as it should.

Perhaps we’ve gotten reparations entirely backwards. Here we must return to Julie and the enslaved peoples of the Douglas plantation. Any program of reparations must begin with them and their descendants. Reparations that flow back to the university itself either in the form of goodwill or an improved campus experience are not reparations. Diversity initiatives, black studies programs, and slick PR campaigns celebrating the university’s benevolence function primarily to enrich the university while compelling black students and faculty members to labor once more for the institution that owes their ancestors money.

This cannot be a question of what the university will do for black communities. It must be a function of what black communities demand as payment to forgive an unforgivable debt. Black people do not need a seat at the university’s reparations table. They need to own that table and have full control over how reparations are structured.

As more details of the university’s participation in slavery, Jim Crow, and discrimination post-1967 are documented, the current residents and community organizations of the South Side of Chicago must lead the way—not be told where to sit. This is part of a requisite cognitive shift that involves thinking beyond the legal framework of ‘damages,’ or the neoliberal ordering of private property rights, or the monstrosity of capitalism. We must imagine an entirely new model of human interactions, self-governance, and social organization. One that shuns hierarchies and fosters horizontalism. If done correctly, reparations can lead the way to a fresh re-conceptualization of politics—not based in crude self-interest but justice and even love.

Reparations promise us a monumental re-birthing of America. Like most births, this one will be painful. But the practice of reparations must continue until the world that slavery built is rolled up and a new order spread out in its place. Until then, the University of Chicago must begin all of its conversations with the knowledge that it is party to a horrific crime that can never be fully rectified. But still it must try. And through that trying it must embrace an entirely new mission—one that centers slavery, the lives of the enslaved, and their descendants.

*This post is derived from a paper by the Reparations at UChicago Working Group (RAUC), which emerged from a recent session of the University of Chicago’s U.S. History Workshop on “Reparations and the Modern University.”

Caine Jordan is a first-year Ph.D. student in the Department of History at the University of Chicago. His work focuses on race, respectability, and racial uplift in the Civil Rights Movement.

Guy Emerson Mount is a Mellon Foundation Fellow at the University of Chicago and the coordinator of the U.S. History Workshop. His dissertation, “The Last Reconstruction: Race, Nation, and Empire in the Black Pacific,” examines the relationship between the end of American slavery and the birth of American overseas empire. Follow him on Twitter @GuyEmersonMount.

Kai Parker is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Chicago. His dissertation is titled “Redemption in the Godless City: Messianism and Black Chicago, 1930-1968” and explores the intersection of race, religion, and Civil Rights.

Thank you for this stunning essay. It reveals long buried history, and suggests clear actions for the University of Chicago to take in our own time. Accomplishing both tasks in a short essay is quite impressive and meaningful.

Please permit me one simple question. Is there any known relationship between the Stephen A. Douglass who slavery-gained property went to the University of Chicago, and the “Little Giant” Stephen A. Douglass, the U.S. Senator from Illinois? Thank you.

Mark Higbee

Professor of History

Eastern Michigan University

Thank you for reading and sorry if it was not clear that, yes, we are talking about the Senator Stephen A. Douglas of the Lincoln Douglas debate fame. In the longer white paper linked at the bottom of this article (which can also be found here https://app.box.com/s/bd9w85wam0pzwt0wngapkf66vojn9bwy ) we talk a more about how Douglas’s slaveholding intersected with his national political career and the university’s ability to raise funds against the land. We are still at the tip of the iceberg in exploring this aspect of the story.

The Old University of Chicago, which is the one Douglas helped found, went bankrupt in 1886. The final meeting of that university’s Trustees was to formally change the name to “Old University of Chicago” so that a completely distinct legal entity could take the name “University of Chicago.” Connections between alumni, intellectual culture, etc., are of no importance because the funds which were derived from slavery had completely disappeared. The argument that the University was founded by slavery because of a carryover of alumni, culture, architecture, or books is farcical: Should we not hire graduates of Harvard Law School to teach at the Law School because HLS was endowed with money from the Royall Family?

Daniel Simon

A.B. Candidate 2017

University of Chicago

Daniel,

See the lengthier discussion in the paper linked at the bottom of the article, starting at p. 9 ff.

Ditto on white paper reference. Also see my response below to Prof. Baldwin and also read the first chapter of Boyer’s book which really makes mince meat of the whole “Old University of Chicago” fiction.

Same man. Born in Brandon VT

Just some thoughts…Though, I am no historical academician or expert on this particular subject, but as a person of color, and arts administrator. I find the notion of ‘reparations’ fascinating in todays modern day context for past historic and economic transgressions. How to make right historical wrong(s)–that seemingly continue to plague us with adverse, negative effects on a certain people descended from slavery? How do we measure the everyday cultural, economic, housing and psychological stains and torment still impacting those that helped to build these learned esteemed institutions? We applaud the efforts and the strides made by the University of Chicago within the overall communities adjacent to it. The programs are positive, and helpful but more is needed.

No financial renumeration can ever reconcile or undue slavery’s past. Recognition, admission and exposure of the past within universities, colleges and businesses bare the responsibility. I’m not so sure that the new and improved University of Chicago can so easily wipe or walk away from it’s “Old University of Chicago” history, simply because it entered into bankruptcy. The suggestions made by the Guest Poster “A Case for Reparations at the University of Chicago” all are no – brainers. There are plenty of examples already in place for them to follow and lead. Setting a local precedent at the south side campus would be an admirable start necessary towards bridging the gap towards truth and reconciliation here in this city.

This is a stunning and elegantly argued find by these amazing graduate students…bravo! As a scholar of Chicago and the University of Chicago in particular, I personally owe these young scholars a debt of gratitude. I find it equally stunning that a commenter here would suggest that the legal fiction of “The Old University of Chicago” versus “University of Chicago”…probably due to bankruptcy law, would serve as a better indicator of inheritance than ENDOWMENT, let alone the very real connective tissue of alumni (and their donations), culture (specifically around land ownership), and architecture (the gothic style of fortification against its surroundings). Of course there are material and cultural connections here that also cannot be denied. I actually think the outlook of faculty, administrators, and trustees is just as strong when we consider a clear line from the school’s slave endowment to its sponsorship of racially restrictive covenants and finally ending with the school’s role in a national campaign towards urban university-based urban renewal (what locals called Negro Removal). For me this pathbreaking finding about Stephen Douglas is just further confirmation about a clear higher education outlook linking racial difference to economic stability….wonderful work!

Thank you Prof. Baldwin for your kind words! I think we only cited your work once in the longer white paper but you and Prof. Green were in our minds much more than that.

In addressing the prior poster, a couple factual points are in order all of which we cover in the longer white paper (as does Boyer and much of the other secondary material). First, the University of Chicago did not declare bankruptcy. It allowed the Douglas land to be foreclosed on and, consequently, had to temporarily suspend operations at that location (but not at its Morgan Park location where the Div School was housed). The whole thing was an orchestrated strategy to renegotiate the debt they had placed on the Douglas property (with the money from those loans being spent on books, faculty, institutional infrastructure, etc. that continues to benefit the university today). Right up until settling on the current Hyde Park location, the university was trying to buy back the Douglas property for pennies on the dollar as part of this plan but their lender saw right through this charade and refused.

Not only was the university not legally bankrupt during this time but it was also far from impoverished in any real sense of the term (though they did develop a cash flow problem). The vast donor network the university had built up over its first three decades of operation, including Rockefeller, were ready to keep the university afloat provided the right deal could be struck. Trustee and doners quickly found that deal when Marshall Fields put up the land (that was not tainted by Douglas, the debt, and the legacy of slavery) and Rockefeller put up the cash. In the absence of a moral center this was a perfectly sound business decision for the university: why pay off an enormous debt when you can just manufacture a crisis, raise even more money, and then walk way from the debt altogether and get a bunch of brand new facilities? It made perfect financial sense as long as you have no sense of basic justice. The shell game that insured was so shameful that I’d be shocked if any supporter of the university would defend it today if they knew the full story (which is one of the reasons I think Boyer doesn’t endorse that narrative). The whole tortured procedure of changing the name was certainly not a mark of poverty but instead a legal loophole that only further enriched the university’s coffers by design. If the university ends up resisting the call for reparations, this history of refusing to pay its debts and its willingness to engage in legal shenanigans will only appear all the more relevant.

Second, the legal fiction of the so-called “Old University of Chicago” was just that–a fiction. It was also (if adjudicated today) a textbook example of both fraud (which the lenders were screaming about at the time) and alter ego (where a new legal entity shares so many features of a prior legal entity that they are treated as one and the same under the law). Even IF reparations depended upon a fetishized legal discourse rather than a moral and political argument, Dean Boyer has already rightly stipulated that the continuities are so profound that any attempt to argue for a dogmatic and absolute break between the Bronzeville and the Hyde Park locations (or their fictitious business names) utterly fails when confronted with the details of the historical record. This is to say nothing of the fact that saying: “we are two different things because we say we are two different things” is the oldest logical fallacy in the book (see Descartes). I find it hilarious that the University is using this exact same circular reasoning in federal court today (as I write) to claim that “graduate workers aren’t really workers because we say they are not workers.”

The craziest part of all this is that we have only begun to scratch the surface of the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, and post-Civil Rights discrimination at the University of Chicago (as well as the lines between them that you refer to Prof. Baldwin). If four grad students could dig this up in their spare time between teaching, writing dissertations, presenting at workshops, raising a family, etc. etc. I can only imagine what we will be uncovering as we move towards a more sustained and focused effort. Thanks again Prof. Baldwin for reading and engaging with our work.

Wikipedia on the current U of C: The University of Chicago was created and incorporated as a coeducational,[28] secular institution in 1890 by the American Baptist Education Society and a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller on land donated by Marshall Field.[29] While the Rockefeller donation provided money for academic operations and long-term endowment, it was stipulated that such money could not be used for buildings. The original physical campus was financed by donations from wealthy Chicagoans like Silas B. Cobb who provided the funds for the campus’ first building, Cobb Lecture Hall, and matched Marshall Field’s pledge of $100,000. Other early benefactors included businessmen Charles L. Hutchinson (trustee, treasurer and donor of Hutchinson Commons), Martin A. Ryerson (president of the board of trustees and donor of the Ryerson Physical Laboratory) Adolphus Clay Bartlett and Leon Mandel, who funded the construction of the gymnasium and assembly hall, and George C. Walker of the Walker Museum, a relative of Cobb who encouraged his inaugural donation for facilities.[30]

Organized as an independent institution legally, it replaced the first Baptist university of the same name, which had closed in 1886 due to extended financial and leadership problems.[31] William Rainey Harper became the modern university’s first president on July 1, 1891, and the university opened for classes on October 1, 1892.[31]

The first president Harper, an accomplished scholar (Semiticist) and a member of the Baptist clergy, believed that a great university should maintain the study of faith as a central focus, to prepare students for careers in teaching and research and ministers for service to the church and community.[32] As per this commitment, he brought the Morgan Park Seminary of the Baptist Theological Union to Hyde Park, and the Divinity School was founded in 1891 as the first professional school at the University of Chicago.

The best part about Wikipedia: When it’s wrong you can change it.

For more than 4 years, Bronzeville Historical Society has been located at the Senator Stephen A. Douglas Tomb Site. At every event or gathering we host, the names of each man, woman, and child from the Douglas family slave lists are read aloud. Our scholarship has included reaching out to descendants of Douglas and the enslaved descendants from the Pearl River, MS plantation via the Stephen A. Douglas Association. We will never forget all that were held in bondage…

https://www.dnainfo.com/chicago/20130404/douglas/stephen-douglas-slaves-be-honored-before-garden-planting

Thank you very much for this most useful article.

As you may know, in 2009, when what is now called the Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons opened south of B-J, John Boyer decided to name one of the college houses “Oakenwald House” after Stephen Douglas’s South Side estate. I sent him an email protesting this tying of an undergraduate residence hall name to the slavery-supporting Senator Douglas, mentioning Douglas’s notorious backing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Boyer responded by claiming that Douglas’s involvement with that Act was exaggerated; I don’t know if this was just a matter of his ignorance of American history. In any case that house is now called Keller House, though the renaming was because of a donation, rather than a matter of social conscience.

I do, though, have a couple of quibbles. The distinction between “The Old University of Chicago” and the present University wasn’t entirely a legal fiction – there was a very significant consequence in that the State of Illinois refused to grandfather-in the exemption from taxation that the Old University enjoyed, as did Illinois College, Lake Forest College, and Northwestern University (the latter three still benefit from this exemption in the State Constitution). Secondly, reading Guy Emerson Mount’s comment might suggest that Marshall Field put up the land so that the new University could avoid the taint of the Douglas association. But Marshall Field I, who was probably the least philanthropic of any wealthy Chicagoan of his time, had purchased about 64 acres of land in 1879 in western Hyde Park for just under $80,000, and he figured – quite rightly – that he could greatly increase the value of his land by donating 10 acres of it for a college. This was in fact much the same as the reason for Douglas’s 1856 gift of land.

Bob Michaelson

S.B. 1966