A Bandung Conference in Harlem: The Meaning of Castro’s Visit Uptown

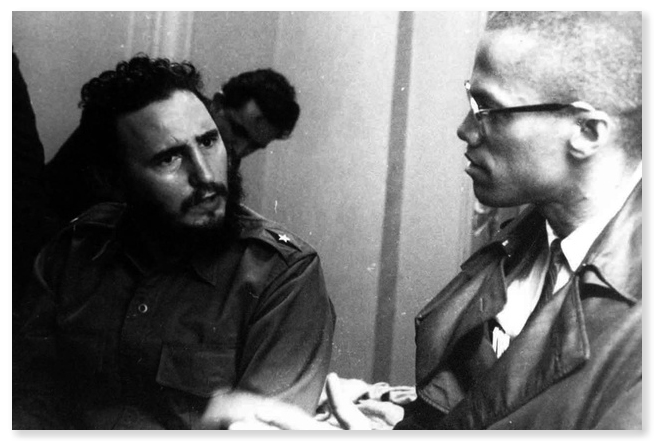

Since Fidel Castro passed away last Friday, news coverage has been predictably polarizing: from celebrating his commitment to anticolonial liberation struggles to (more often) discarding the Cuban revolutionary as the final relic of the Cold War (an honor that more fittingly bestows Henry Kissinger). Crowds in Cuba mourned while crowds in Miami celebrated. President Obama was predictably cordial, while Donald Trump was predictably uninsightful. And on Sunday, as Colin Kaepernick took the field against the Miami Dolphins, he was booed for previously supporting Castro by wearing an X cap and tee-shirt with photos from the famous meeting between Malcolm X and Castro at the Hotel Theresa.

Indeed, as Robert Greene points out, “Castro’s complicated legacy is being played out in the act of obituary writing.” One aspect of that legacy is Castro’s significance to Pan-Africanism and African liberation struggles, a relationship that was first tested and outlined during that visit. Yet while the meeting between Malcolm X and Castro has been emblazoned on tee-shirts, its greater importance lies in bringing an informal band of independent Third World leaders to Harlem in 1960.

In April 1959, Malcolm X had called for a “Bandung Conference” in Harlem while addressing an African Freedom Day Celebration in front of the famed hotel.1 After words by Manhattan Borough President Hulan Jack and Charles T.O. King, the ambassador of Liberia to the United Nations, Malcolm argued that it has “been since the Bandung Conference that all dark people of the earth have been striding toward freedom.” It was at this conference that all dark people recognized a common enemy: “Call him Belgian, call him Frenchman, call him Englishman, colonialist, imperialist, or European . . . .but they have one thing in common: ALL ARE WHITE MEN!”2

Held in Indonesia from April 18–25, 1955, the Bandung Conference marked the first major articulation of the nonaligned movement. It voiced a shared commitment to anticolonialism and self-determination, carving out a third path beyond the bipolar struggle between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Richard Wright summed up the goals of the conference through the terse phrases of a newspaper article: “The West is excluded. Emphasis is on the colored nations of the world . . . Colonialism is out. Hands off is the word. Asia is free. This is perhaps the greatest historic event of our century.”

If Bandung represented, in the words of Brenda Gayle Plummer, a “break in the Cold War ice,” visits by Castro and Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser to Harlem in 1960 “constituted an opening volley in the assault on Cold War bilateralism.” As Castro and his delegation arrived in New York City for the U.N.’s General Assembly, the Cuban government had just seized U.S. banks and tobacco production in Cuba and the Eisenhower administration cut diplomatic ties and squeezed its embargo of the small Caribbean island even more tightly.

Despite preparations for Castro to stay at the Shelburne Hotel just blocks from U.N. headquarters, the owner balked: “Someone told me that the New York Police Department was prepared to put up tents in Central Park for Castro and his party. Maybe that’s not a bad idea.”3 When the group finally reached the Shelburne, the hotel demanded Castro put down a second $10,000 cash deposit to cover potential damages by his delegation. Furious, Castro now threatened to sleep in Central Park, noting that Cubans “are mountain people. We are used to sleeping in the open air.”4

Malcolm X seized upon this opportunity and invited Castro to stay at the legendary Hotel Theresa. As Castro’s delegation moved uptown, community activists rushed to prepare for his arrival. At a meeting of the Harlem Writers Guild Workshop, author Sarah Elizabeth Wright remembered that “we scrambled for our coats and headed uptown to cheer Fidel, to make sure no harm befell him.” Despite the proliferation of photographs from the historic thirty-minute meeting between Malcolm X and Fidel Castro, the only press present were journalists Ralph Matthews and James Booker and photographer Carl Nesfield.

Part of the tremendous energy captured in Nesfield’s photos was a result of the men’s desperate gesticulations as they tried to communicate across the language barrier. Malcolm welcomed Castro to Harlem by saying: “Downtown for you, it was ice, uptown it is warm.” Castro smiled and told him “Aahh yes, we feel very warm here.” Before leaving, Malcolm offered a closing parable: “No one knows the master better than his servants. We have been servants ever since we were brought here. We know all his little tricks. Understand? We know what he is going to do before he does.”5

As Devyn Spence Benson points out, Castro’s anti-racist agenda within the Cuban revolutionary government was relatively new—itself a product of Afro-Cuban activists who “viewed the change in government as a moment to push for their agenda.” Despite seeing the move to Harlem as an opportunity to rankle the Eisenhower administration and make overtures to people of color, Castro’s entire 80-person delegation was white. Thus, Afro-Cuban leader Juan Almeida was wired so, in Benson’s words, “they could show that there were high-ranking black and brown leaders in Cuba.” Robyn Spencer also importantly noted on Twitter this weekend that Cuba was not always what black revolutionaries imagined, and some such as Eldridge Cleaver and Robert F. Williams later left Cuba over political disagreements.

But while Castro’s Harlem visit was partly meant to shape international perceptions about the Cuban revolutionary government, Harlemites were also using the exposure against the United States’ Achilles heel in the Cold War: racial discrimination. James Hicks clearly laid this strategy out after the Soviet Union’s Nikita Khrushchev joined Castro in Harlem: “Castro wounded the United States by moving into Harlem’s Hotel Theresa. Khrushchev rubbed salt into the wound by hopping into a Cadillac and rushing uptown to visit his old friend Fidel.” Hicks believed those in Harlem were sophisticated enough to recognize that their “one big weapon in this fight with bigoted white Americans is to try to shame this white American bigot in the eyes of the world as a man who will not practice what he preaches.”6

But Castro’s visit to the Hotel Theresa was most impactful by establishing an important precedent at the U.N.’s 15th General Assembly: a host of leaders interested in anti-racism, anticolonial politics, and nonalignment, would travel uptown over the next several weeks as part of this informal Bandung Conference in Harlem. Castro was soon joined not only by Nasser, but also Jawaharlal Nehru of India and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. As representatives of darker nations (and also Islam in Nasser’s case), these leaders held even more meaning than Castro for the people of Harlem. Three thousand gathered as Nasser came to meet Castro, some holding “Viva Nasser!” and “Viva Castro” signs, and others signs that read “Congo for the Congolese” and “Allah is the Greatest.” One Muslim man in attendance traced the meeting’s significance back to Garveyism: “It has proved the quotation made forty years ago by Marcus Garvey that someday the black man’s heritage will surround him and the world.”7 A week later, having condemned South African apartheid and U.S. intervention in the Congo before the U.N., Nkrumah made the trip uptown. “I wanted you to know that my presence in Harlem would show the solid bond we feel between the people of Africa and the Afro-Americans in this country,” he told a crowd of 1,500 gathered in front of the Hotel Theresa.8

Three of the figures who organized and spoke at the African Freedom Day Celebration in 1959—Malcolm X, Hulan Jack, and James Lawson—now introduced Nkrumah. A year after Malcolm called for a Bandung Conference in Harlem, a group of anticolonial Third World leaders had gathered at the very spot of his proclamation in the cultural and political heart of black America. As one man in the crowd reflected, “I feel that what’s taking place in Harlem now is the first step forward taken by diplomats. The second step is for the people to take advantage of this and unify.” As if to encapsulate this sentiment, a six-foot sign at the rally read: “We are united!”9 As we unpack the complicated meaning of Castro to 20th-century revolutionary movements, we should remember that more significant than any one meeting between two legendary leaders was the spirit of Bandung alive in Harlem that September.

Garrett Felber is a scholar of 20th-century African American history. He earned a PhD at the University of Michigan in the American Culture Department. His scholarship has been published in the Journal of African American History, South African Music Studies, and SOULS. He has also contributed to The Guardian, The Marshall Project, and Viewpoint Magazine. He is the co-author with Manning Marable of The Portable Malcolm X Reader. Follow him on Twitter @garrett_felber.

- “Malcolm X Calls for Bandung Conference,” Los Angeles Herald-Dispatch, April 23, 1959. ↩

- Malcolm X FBI File, Summary Report, New York Office, November 17, 1959, 48–49. ↩

- “N.Y. Hotels Rebuff Castro,” The Globe and Mail, September 17, 1960. ↩

- Max Frankel, “Fidel Complains to U.N. Angry Castro Quits Hotel in Row Over Bill; Moves to Harlem,” New York Times, September 20, 1960. ↩

- Ralph Matthews, “Going Upstairs – Malcolm X Greets Fidel,” New York Citizen-Call, September 24, 1960. ↩

- James Hicks “Our Achilles Heel,” Amsterdam News, September 24, 1960. ↩

- Sara Slack, “Nasser, Nehru Visit Harlem,” Amsterdam News, October 1, 1960. ↩

- Hazel La Marre, “Africa and the World,” Los Angeles Sentinel, September 29, 1960. ↩

- Slack, “Nasser, Nehru Visit Harlem.” ↩

Thank you for your commentary on the significance of the late Cuban leader’s 1960 visit to Harlem and the symbolism attached to the meeting between those two great leaders, Fidel Castro and Malcolm X.

Dr. Rosemari Mealy

Author -Fidel and Malcolm X-Memories of a Meeting-Black Classic Press 2014

Black Classic Press 2014

Thank you Dr. Mealy! I highly recommend your book to anyone wanting to learn more about the context and significance of this meeting.