Creating an African American Identity and a New Nation

This is a guest post by Daniel R. Mandell, Professor of History at Truman State University. Prof. Mandell recently received the award for Distinguished Literary Achievement from the Missouri Humanities Council in recognition of his many publications on Native Americans in New England between 1600 and 1900. His most recent book, King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the End of Indian Sovereignty (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), written for general readers and college survey classes, was named an “Outstanding Academic Title” by the American Library Association’s Choice magazine. His previous publication, Tribe, Race, History: Native Americans in Southern New England, 1780-1880 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), was given the inaugural Lawrence Levine Award in 2008 by the Organization of American Historians for the best book on American cultural history.

This is a guest post by Daniel R. Mandell, Professor of History at Truman State University. Prof. Mandell recently received the award for Distinguished Literary Achievement from the Missouri Humanities Council in recognition of his many publications on Native Americans in New England between 1600 and 1900. His most recent book, King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the End of Indian Sovereignty (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), written for general readers and college survey classes, was named an “Outstanding Academic Title” by the American Library Association’s Choice magazine. His previous publication, Tribe, Race, History: Native Americans in Southern New England, 1780-1880 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), was given the inaugural Lawrence Levine Award in 2008 by the Organization of American Historians for the best book on American cultural history.

***

On January 13, 1777, Prince Hall and seven other black men petitioned the Massachusetts General Court on behalf of “a great number of Negroes,” insisting that they had “a natural & unalienable right” to freedom. That was the fifth such plea since 1772, but this one created a new pattern in wielding Enlightenment language of liberty and rights. These appeals are often used to highlight the contradictions between slavery and the ideals of the American Revolution, but also—and perhaps just as significant–they contained the earliest expression of African-American identity. They reveal a people who identified as Africans and Americans and who held strong trans-Atlantic connections transcending nation and liberal individualism, and who, at the outset of the war, embraced Enlightenment ideals, sentimentalism, and Protestant notions of virtue.1 They demonstrate that the new nation and the African American community emerged together, linked from the beginning.

These freedom petitions were grounded in the unique nature of colonial New England slavery. Africans and their descendants remained a small minority and generally adapted to the dominant culture and were even encouraged to learn to read; most lived in port towns, a sizeable minority was free, and they often worked and socialized with white laborers. But they also gathered in local annual “Negro elections” to party and elect a representative.2 While individual New Englanders had occasionally challenged slavery, the collective petitions were clearly linked to rising American anger against British imperial measures.

The first came on January 6, 1773, as Boston radicals organized regional opposition. “Felix” submitted a plea from “many slaves” for “relief” (but not freedom), with appeals to Christianity, the recent Somerset ruling in England (that slavery could not exist unless established by written law), and patriarchal norms (bemoaning they were not allowed to control their wives or own property). Three months later came a very different petition, calling explicitly for freedom and printed for wide distribution – showing support from wealthy powerful men. It began by noting that “We expect great things from men who have made such a noble stand against the designs of their fellow-men to enslave them”—a heavily ironic reference to the Stamp Act and other British measures—and then went on to demand freedom (a “natural right”) and the opportunity to earn enough to go live in Africa. Approximately one year later, in May and June of 1774, came two more petitions. The first emphasized how slavery destroyed the natural order, including masculine authority over one’s wife. The petitioner asked to be “liberated” and land for farms, whereas the second focused on religion, even hinting at a connection between black servitude and Israelite slavery in Egypt, and asked for their “Natural rights or freedoms” but not land.

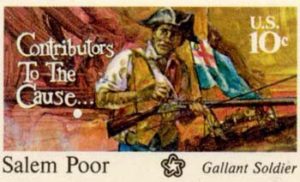

When war erupted, African Americans demonstrated that they were part of the New England community and deserved liberty like their neighbors. African Americans with town militia fought at Concord and Bunker Hill, and throughout the war most African American soldiers served in integrated units—an experience not to be repeated until the Korean War.3

When war erupted, African Americans demonstrated that they were part of the New England community and deserved liberty like their neighbors. African Americans with town militia fought at Concord and Bunker Hill, and throughout the war most African American soldiers served in integrated units—an experience not to be repeated until the Korean War.3

Six months after Congress declared American independence came the Prince Hall petition. It began by referring to the Declaration, insisting they had “a natural & unalienable right” to freedom, and then appealed to moral sensibility (seen as connected to higher reasoning) by charging that the “cruel hand” of the slave traders had “unjustly dragged” them “from the embraces of their tender Parents” in violation of the “Laws of Nature & of Nation” and “all the tender feelings of humanity.” The petitioners connected those “tender feelings” to an idyllic African past, noting they had been stolen from “a populous, pleasant and plentiful Country,” rather than the usual “dark and savage” African continent. Of course they also made a number of connections between black emancipation and the Revolution’s resistance to British “Bondage & Subjection.” The petition called on the state to enact gradual emancipation but said nothing about relocating to Africa. Very similar demands appeared in petitions in Connecticut and New Hampshire in 1779; in the latter, the “natives of Africa” told state officials that “the God of Nature gave them life and freedom, upon terms of the most perfect equality with other men”–radical language that reflected the experience of fighting in the Revolution.4

The petitions demonstrate that black people in different parts of New England claimed an African identity during the American Revolution. Historians generally note this tendency with the “African” churches and societies at the turn of the century. But these petitions clearly show that identity emerging during the Revolutionary crisis. While we know little about the signatories, we do know that a large percentage was born in the Americas or perhaps even in Europe. Somehow newcomers and creoles, free and enslaveda together created this African American identity, showing that the idea of being African, like other modern ethnic identities, was not indigenous to that continent but was shaped by individuals originally from different places, writing in America and in England, often for political motivations.

Phyllis Wheatley played a critical role in this development. Enslaved in West Africa as a child, she was sold in Boston to a family where she was taught to read and began writing poetry. In 1773, her Poems on Various Subjects was published to great acclaim in England and America; one poem celebrated the repeal of the Townshend Duties and informed her readers that her “love of Freedom” came because when young she “Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat,” and since could only wonder “What sorrows labor in my parents’ breast?” This seems the clearest source for the subsequent petitions that praised Africa and condemned the slave trade in terms that appealed to emerging sentimentalism.

These petitions formed, or at least represented, what quickly became the dualistic nature of African American identity, drawing on both their quasi-racial origins and their participation in the American Revolution. These documents not only indicate that an African American identity emerged during the Revolution, but also highlight the essential links between their embrace of the Revolution and rapid adoption of an African identity. African American petitioners used the upheaval, rich language, and political and intellectual opportunities of the Revolution to develop, claim, and promote an idealized vision of their past, and to join that memory to Enlightenment concepts of natural rights and human equality. In this fashion, Revolutionary rhetoric and memories—African and American—became vital aspects of black identity.

While it might seem contradictory that the American Revolution became the stage for the emergence of an African identity among this trans-Atlantic people, the rich intellectual and cultural stew of the Revolutionary crisis developed in similar ways among Anglo-Americans as they drew contemporary lessons in politics from memories of resistance to arbitrary authority, from King Charles I to Sir Edmund Andros. Just as these provincials reached back to an often-imagined past in order to justify a radical break with the present, so, too, did black petitioners.5

After the Revolution, this intertwining of African and American identities with threads of Revolutionary ideals was brittle and sometimes contested. During the early Republic, blacks organized “African” self-help societies and churches and in the face of intensifying hostility some made efforts to leave for Africa, but they also embraced the emerging American values of education and enterprise, and joined in the larger public sphere despite increasingly violent racism. “Negro elections” gave way to parades and banquets to celebrate the end of the slave trade, American independence, local emancipation, and the future abolition of slavery. Organizations became “Colored American” instead of “African.” But the Revolutionary War remained a strong link between the black community and the larger American experience. In 1851, a committee of leading Boston African Americans staked their connection to that increasingly sacred event, petitioning (unsuccessfully) the Massachusetts legislature to erect a statue to Crispus Attucks as its first martyr. Four years later, the head of that committee, William Cooper Nell, published the first African American historical study: Colored Patriots of the American Revolution.6

* * *

This essay is a shortened version of “A Natural & Unalienable Right”: New England Revolutionary Petitions and African American Identity, in Remembering the Revolution: Memory, History, and Nation-Making from Independence to the Civil War, eds. Robert Aldrich et al. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013), 38-53.

- Two literary studies with different views of the genesis of African American identity are Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993); and Philip Gould, “Early Black Atlantic Writing and the Cultures of Enlightenment,” in Beyond Douglass: New Perspectives on Early African American Literature, eds. Michael J. Drexler and Ed White (Lewisburg, Penn.: Bucknell University Press, 2008), 107–22. ↩

- William D. Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988). ↩

- Sidney Kaplan, The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution (Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press, 1989). ↩

- Kaplan, Black Presence, 29, 30, 49-50. ↩

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967). ↩

- Patrick Rael, Black Identity and Black Protest in the Antebellum North (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Holton, In Hope of Liberty: Culture, Community and Protest Among Northern Free Blacks, 1700-1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997). ↩

Such an interesting story of black petitioners who educated themselves in the ways of colonial laws and used that language to better themselves. Bravo!

This is a great way to explore a rich and often neglected aspect of American history. It is fascinating to see aspects of this play themselves out currently in terms of ethnicity being defined as African or Black American. The relationship of that definition between immigrant or first generation African Americans and those whose history in America is far longer. Bravo.