“Africa for the Africans”: The Expanding Field of Global Garveyism

Recently, the Global Garveyism conference took place at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia. Organized by Professors Adam Ewing (Virginia Commonwealth University) and Ronald Stephens (Purdue University), the Global Garveyism Conference brought together a dynamic crowd of scholars, students, activists, and members of the community interested in the study of Marcus Garvey’s teachings and philosophy. It was, to my knowledge, the first major academic conference on Garveyism held in the United States to date. In 1987, Professors Rupert Lewis and Patrick Bryan held a Garveyism conference in Jamaica, bringing together some of the most esteemed Garvey scholars–Tony Martin, Honor Ford Smith, Horace Campbell, and Judith Stein among them–to commemorate the centennial of Garvey’s birth. This seminal meeting resulted in the publication of a foundational text entitled Garvey: His Work and Impact.

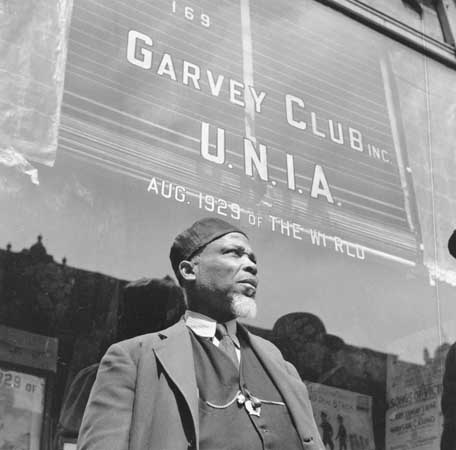

In similar fashion, the recent Global Garveyism conference featured the scholarship of almost twenty distinguished scholars whose research has been fundamental to understanding the richness and complexity of Garveyism in the United States and across the globe. Given his extensive and prolific research on Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), it was certainly fitting that Professor Robert A. Hill, the editor-in-chief of the multi-volume edition of The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, should be the keynote speaker for this significant gathering. Marking the official opening of the conference, Hill delivered a keynote address in which he traced the intellectual genealogy of the phrase, “Africa for the Africans” from its earliest articulations in the early nineteenth century to the 1950s. His presentation captured the underlying goal of the conference–to highlight the significance of Garveyism while also paying attention to the ideological underpinnings of the movement and its enduring legacies.

On the second day of the conference, presenters grappled with a number of core themes in Garveyism Studies and particularly emphasized the movement’s widespread impact in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. The first session, “Garveyism in the British West Indies,” included two fascinating papers by José Andrés Fernández-Montes de Oca and Nicole Bourbonnais. Building on the foundational works of Lara Putnam, Honor Ford Smith and others, Fernández-Montes de Oca and Bourbonnais, respectively, introduced new and exciting work that revealed how labor activists in Trinidad drew on the principles and teachings of Marcus Garvey, and underscored the crucial role of women in the UNIA’s “Harmony division” in Kingston, Jamaica. The second panel, “Africa in the Diaspora,” chaired by Stephen G. Hall, featured three excellent papers–by Robert Trent Vinson, Erik S. McDuffie, and Brandon R. Byrd–that shed new light on the impact of Garveyism in South Africa, West Africa, and across the U.S. Midwest and the Great Plains. Collectively, the papers on this panel highlighted the diverse practices and ideas of Garveyite activists on the local, national, and international levels and in so doing, challenged the notion that Garveyism, as an ideology, was somehow fixed in time and space.

The remaining panels and presentations on day two further captured the depth and complexity of Garveyism–as articulated by activist-intellectuals in various locales throughout the United States and other parts of the African diaspora. From Asia Leeds’s brilliant presentation on diasporic consciousness, West Indians, and Garveyism in Costa Rica to John Maynard’s fascinating paper on Marcus Garvey and the Rise of Australian Aboriginal Political Protest, presenters grappled with the theme of black internationalism, centering the global dimensions of Garveyism as both a movement and ideology.

Several presenters at the conference also shared new research on the varied articulations of Garveyism on the grassroots level in the United States, paying close attention to the activism of black men and women in rural areas. The panel, “Leadership Struggles and Rank-and-File Visions of American Garveyism,” featured three significant papers from Jahi Issa, Ronald J. Stephens, and Gabriel Selassie I. Building on the scholarship of Mary G. Rolinson (who chaired the panel), Claudrena Harold, Randall Burkett and others, the panel centered on the influence of Marcus Garvey among rural activists in the U.S. South and also examined the deployment of cultural and religious symbols in UNIA divisions. By focusing on local politics and rank-and-file activists in the UNIA, the panel shifted focus from “the preacher to the pews” (so to speak) by emphasizing the experiences and the ideas of ordinary men and women whose vision for black liberation aligned, yet at times departed from, Garvey’s. Some of these core themes re-merged at the community forum (moderated by Evandra Catherine), in which community leaders and activists Mwariama Kamau, Jahi Issa, Free Egunfemi, and Attalah Shabazz reflected on the legacy and lessons of Garveyism in our current political climate.

The third and final day of the conference began with a panel on “Continuities and Legacies,” chaired by Ula Y. Taylor. The panel included papers by me, Michael O. West, and Caroline Shenaz Hossein. My paper analyzed the writings of Garveyite women in global black newspapers during the 1940s, revealing how these women engaged Pan-Africanist discourses against the backdrop of World War II. West’s paper provided a sweeping yet nuanced portrait of global black liberation struggles from the Age of Revolution to Black Power–situating Garveyism as a “window on the past, present, and future of black struggles and aspirations globally.” Hossein’s paper illustrated this point, revealing how Garvey’s teachings continue to inform the financial practices of many black men and women currently residing in Canada and various parts of the Caribbean.

The final roundtable, “Reflections on Global Garveyism,” included closing remarks by Ronald J. Stephens (moderator), Robert A. Hill, Frank A. Guridy, Mary G. Rolinson, and Ula Y. Taylor. Each presenter shared their take-aways from the conference with several grappling with the question of what Garveyism offered black men and women during the twentieth century and reflecting on what it offers in this contemporary moment. Hill expressed an appreciation for the new directions in the scholarship and emphasized the need for scholars to pay close attention to the local, national, and international contexts. Indeed, as Guridy noted, we must locate Garveyism in a migratory and diasporic story even as we tell a history that is grounded in local and national narratives. Taylor emphasized the need to further expand scholarship on women and gender politics and Rolinson called for more scholarship on Francophone Garveyism as well as more work on Garveyism in the U.S. South. In addition, Rolinson called for more collaboration among scholars especially as it relates to compiling and sharing primary sources. To that end, she suggested digitizing the Negro World and also working on building a website to collect data (including oral interviews).1

As I reflect on the Global Garveyism conference, I am excited about how this field is rapidly growing and expanding. For far too long, Garveyism has been marginalized in the academy and this conference–as well as the recent publications of seminal books and articles by Robert Trent Vinson, Adam Ewing, Erik S. McDuffie and others–signify the dawn of a new phase of Garveyism Studies. Moreover, it is wonderful to see so many scholars building on the groundbreaking work of Ula Taylor, Barbara Bair, Honor Ford Smith and others, by centering women’s voices and highlighting the gender and sexual politics of Garveyite men and women. I encourage more scholars to take up the challenge and reiterate the point I made in an earlier piece: “we must be vigilant and intentional about ensuring that we do not replicate masculinist narratives.”

The Global Garveyism conference provided fertile ground for addressing these and other crucial concerns, and it highlighted some of the best and most innovative work being done in the field. I am honored to be included in this dynamic group of scholars who are asking new questions and utilizing new methods and methodologies to shed light on the rich and complex history of Garveyism, Pan-Africanism, and black internationalism. I look forward to the publication of Ewing’s and Stephens’s anthology, Global Garveyism: Diasporic Aspirations and Utopian Dreams (forthcoming, University Press of Florida), which will no doubt be a field-defining (and field-transforming) collection of groundbreaking essays.

- Since the conference ended, Robert A. Hill and Frances Peace Sullivan have shared several links to digitized versions of the Negro World including those provided by Readex and the Center for Research Libraries. ↩

I have read briefly about Garveyism but, thought it was historical. I’ll watch for its resurgence in the future.

Vincent: Yes, it’s “historical.” But, certainly the past informs the present. That was one of the key points we discussed at the conference. And by the way, there are still UNIA chapters across the country (including Richmond, VA where the conference was held).

This is beautiful, especially, coming out of my home state of Iowa. Garvey’s legacy will live on forever in the hearts and souls of many. I thank God for your friendship, Bobby, as it brought with it not only tons of fun and laughter over the years since I met you in 1970 at Cornell, your second stop after arriving in America, but also a complete soaking up of the thoughts, opinions and ideas of this brilliant, visionary Brother Garvey. Thanks a million, my friend, for inspiring so many to keep Garvey’s ideas alive and well.

Dwight: Thanks so much for reading. Glad you found the piece useful and nice to hear about your friendship with Bobby.