The ‘Capitalized Womb’: A Review of Ned and Constance Sublette’s The American Slave Coast

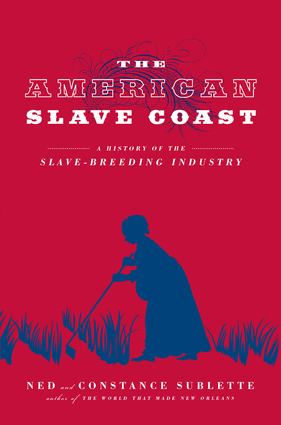

Recently, I was asked to sit on a panel at the CUNY Graduate Center to discuss Ned & Constance Sublette’s new book, The American Slave Coast: A History of the Slave Breeding Industry. There have been a handful of books that examined slave breeding dating back to 1931 when Frederic Bancroft wrote Slave Trading in the Old South, which surveyed how the breeding and rearing of enslaved people was a commercial enterprise to expand slavery further westward. However, it was not until Deborah Gray White debuted Ar’n’t I a Woman: Female Slaves in the Plantation South that scholars gained a fuller portrait of the lived experiences of enslaved women regarding sexual violence and reproduction. In the past several years, the field has made more of an effort to discuss slavery from an economic standpoint. Recent scholarship such as Edward E. Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton: A Global History, and Walter Johnson’s River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in Cotton Kingdom, among other books, reveal how America’s cherished institutions and presidents created and accommodated the slave trade. Nonetheless, the Sublettes have enriched the field by offering a painstaking, multi-dimensional portrait of the political, social, and economic consequences of bondage. Even referring to slavery as the “peculiar institution” masks the immense prosperity that was built and sustained by black labor and black wombs.

The Sublettes have managed to coin the brutal economic system that kept the institution of slavery alive as the “capitalized womb” (p. 24). They argue that the “capitalized womb” illustrates how enslaved women’s bodies served as the engine of the slave breeding industry and powered a global economy for cotton consumption. Their new book ties the violent experiences of enslaved women directly to the market. It tells the brutal story of how the slave industry made the reproductive labor of the people it referred to as “breeding women” essential to the country’s expansion. They contend: “In a land without silver, gold, or trustworthy paper money, enslaved women’s children and their children’s children into perpetuity were used as human savings accounts that functioned as the basis of money and credit.” In short, slaves were money.

The Sublettes take readers through the strategic closing of the slave trade in 1808 to the Emancipation Proclamation, which “decommissioned the capitalized womb” and sanctioned armed resistance during the Civil War. In Virginia, slaveowners competed with South Carolina over African importation. When the trade was closed, Thomas Jefferson, who is featured prominently throughout the book, gained a major victory by engineering Virginia as a “breeding state” to supply high priced slaves throughout the South and Deep South. When the domestic slave trade exploded during Andrew Jackson’s presidency, piracy to Latin America was virtually unenforced. The Sublettes argue that the enormous amounts of wealth generated by American slavery led to attempts to annex Cuba (which controlled 21% of sugar production) and other parts of Latin America.

This work compelled me to think about how the concept of slave breeding is grossly misunderstood within the American consciousness. Think of Barbara Fields’s famous article, “Slavery, Race, and Ideology in the United States of America.” It opens with sports announcer Jimmy “the Greek” Snyder, who in 1988, stated that lack of black coaches in basketball was due to racial differences. He remarked that black athletes had an advantage because they had longer thighs than white athletes due to slave breeding. “This goes all the way to the Civil War, Snyder explained, “When during the slave trading… the owner, the slave owner, would breed his big black to his big woman so he could have a big black kid you see.” Fields states, “Astonishing though it may seem, Snyder intended his remark as a compliment to black athletes.” Snyder was promptly fired, but nevertheless it’s safe to say his rationale was not far from what many people believed, but did not dare say.

More recently, in 2014, Saturday Night Live aired a skit with comedian Leslie Jones in which she discussed People Magazine’s designation of Lupita Nyong’o as their “Most Beautiful Person.” Nyong’o had recently won an academy award for her portrayal of Pastey in 12 Years a Slave. On page 33 of The American Slave Coast, the Sublettes examine Jones’ attempt at transgressive humor:

“See I’m single now, but back in the slave days, I would have never been single. I’m 6 feet tall and I’m strong. I mean look at me, I’m Mandingo. I’m just saying that back in the slave days, my love life would have been way better. Master would have hooked me up with the best brother on the plantation, and every nine months I’d be in the corner having a super baby.”

The backlash from twitter and social media was swift and fierce. The idea of a “love life” in slavery was nothing more than a distasteful joke about rape. Fortunately, for Jones, comedians are somehow immune to the practice of apology. Unlike Snyder, she kept her job. In fact, Jones did not back down. “I would have been used for breeding straight up. That’s my reality.”

In truth, enslaved women’s reproductive life cycle was composed of rape, pregnancy, giving birth in a field and, with little to no recovery, within six to twelve weeks one could be pregnant again. Childbirth began at a young age. The authors state that the “only age bracket in which females outnumbered males in the trade was twelve to fifteen,” (p.5) when girls were old enough to do field labor and bear children. Again and again, the Sublettes provide the gripping historical narratives of the sobering reality of enslaved women’s reproduction. When a master referred to “Two of the best breeding wenches in all of Maryland,” he claimed, “One was 22 and the mother of 7 children, the other 19 years old with 4 children.” The slaveowner contended these women were “a steal at $1000 a piece, but he would sell them at $1200 for the pair” (p. 7). The Sublettes constantly remind their readers that wealth accumulation was always at the center of slavery, for the moment a baby was born, a master could begin accruing interest on the infant, who had a cash value at birth. Violence, sales, and separation were the grim reality of enslaved women. Both Snyder and Jones represent just the benign examples of how we improperly understand this history.

The Sublettes also tell the story of an enslaved woman named Celia, who is purchased to be a sex slave and raped moments after her purchase. After years of abuse, Celia refuses her master’s advances and hits him over the head, killing him. She is caught and charged for murder. Celia claimed that she was a victim of rape and that she was defending herself. The Sublettes write, “There was, then, legally no such thing as the rape of an enslaved woman. As Missouri court effectively affirmed that rape was legally what Saidiya Hartman calls ‘the normative condition’ for enslaved women in the state”(p. 35). In 1855, Celia was hung at age 19 for killing the man that raped her. What the Sublettes do not reveal is that Celia was pregnant when she was sentenced and the judge waited until after she gave birth to hang her. This was not an act of mercy, but an act of capital. Celia’s baby had economic value. However, Celia’s baby was stillborn. Her only reprieve might have been that her child was born dead and unable to be raised in a world that sought to oppress and exploit its potential labor.

Three themes surface throughout the book. The first is the notion that black women are essentially, legally un-rapeable. This is an industry of rape, and even the term slave breeding has become euphemism for a reality we’d rather not discuss. Enslaved women had no right to their bodies, no right to their children, and no right to refuse forced breeding. Second, is the idea that there is no such thing as a black child. Black children do not exist, only smaller, younger versions of enslaved bodies. They can be sold, beaten, raped, killed, and discarded. Third, and perhaps most important, is how the slave breeding industry “demonstrates how far the unrestrained pursuit of profit can go” (p. 668). The state of Mississippi had more millionaires than any other and the Sublettes speculate that had Cuba been annexed to the United States, Mississippi would have served as a slave breeding state for the entire island. Prosperity depended upon the continuous flow of enslaved bodies.

Three themes surface throughout the book. The first is the notion that black women are essentially, legally un-rapeable. This is an industry of rape, and even the term slave breeding has become euphemism for a reality we’d rather not discuss. Enslaved women had no right to their bodies, no right to their children, and no right to refuse forced breeding. Second, is the idea that there is no such thing as a black child. Black children do not exist, only smaller, younger versions of enslaved bodies. They can be sold, beaten, raped, killed, and discarded. Third, and perhaps most important, is how the slave breeding industry “demonstrates how far the unrestrained pursuit of profit can go” (p. 668). The state of Mississippi had more millionaires than any other and the Sublettes speculate that had Cuba been annexed to the United States, Mississippi would have served as a slave breeding state for the entire island. Prosperity depended upon the continuous flow of enslaved bodies.

The painful history of rape, auction, and abuse can never be fully told, not even in the 754 pages of The American Slave Coast. If ever black lives needed to matter, it was during chattel slavery. However, in The American Slave Coast, black lives only matter as it relates to their economic value and their ability to produce and reproduce. Despite the length, the Sublettes have constructed a heart rending, compelling, brilliant, and highly readable book, one that is best read out loud. Indeed, if we fail to understand how black bodies mattered in the past, we will surely misunderstand the movement and meaning in the present.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Excellent book review of an excellent book! The book is on my wish list.

I read this article a while ago that discussed the idea that racism was an invention of capitalism as rationale for slavery. The article is entitled

‘Is Racism A Capitalist Ideal?’

http://www.bcurrentmag.com/is-racism-a-capitalist-ideal/

Thank you so much for posting these articles! I post them to my Facebook. I’m looking forward to the next article. Good job Ms. Jackson!

Many thanks! So glad you liked it! The book really is amazing and very readable.

In solidarity.

As a white American man born of relative privilege and infected by internalised institutional racism, I have a responsibility to read and understand what was done and how those actions continue to reverberate today. Now as an Australian citizen, it helps inform my understanding of Aboriginal Australians. Your review gave me a glimpse into important history. Sharing…