Losing Willie McGee

The toll a failed political campaign takes on an individual can be devastating, none more so than when a life hangs in the balance. When Willie McGee was executed by the state of Mississippi in 1951, his loss was felt deeply by progressives and leftists who spent years trying to exonerate him. That frustration and disappointment was expressed in poetry and in taking to the streets to avenge him. Losing Willie McGee became a symbol of the uphill battle Cold War civil rights advocates faced in trying to expose an unjust legal system stunted by racism and anticommunism.

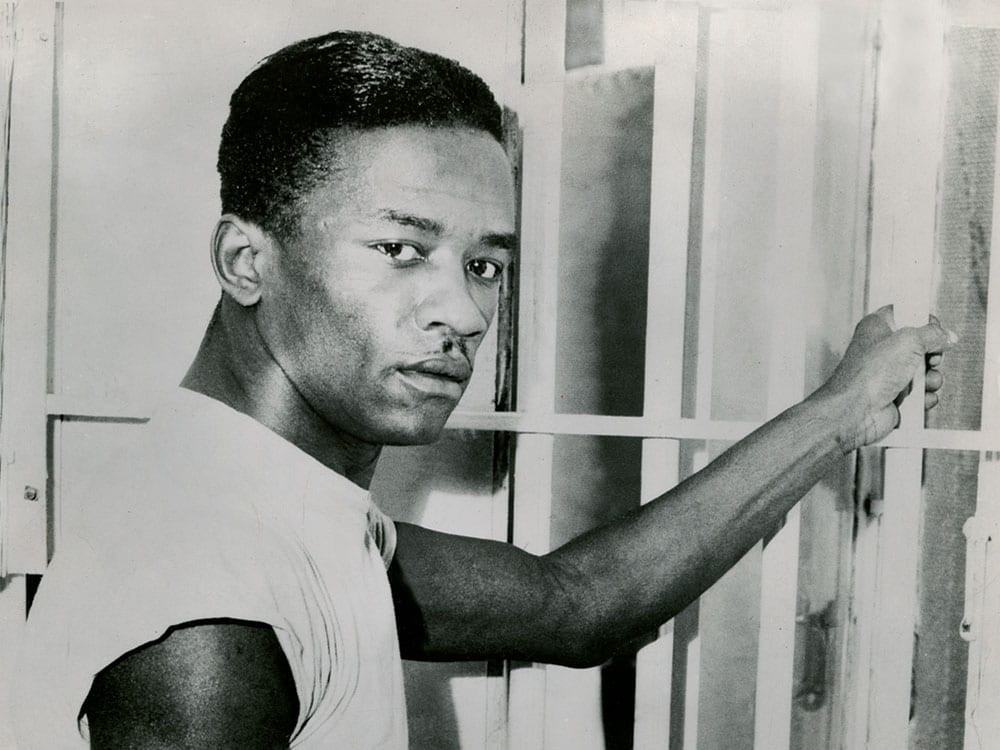

In November 1945, Willie McGee, a World War II veteran was arrested in Laurel Mississippi for the alleged rape of a white woman named Wiletta Hawkins. Hawkins claimed that McGee broke into her home and raped her while her husband was asleep in the next room, she reported the assault two days later. The police initially arrested several Black men for questioning and zeroed in on Floyd Nix who worked for the Hawkins family. But the next day McGee was arrested and taken to Jackson for questioning where he was held for a month without benefit of an attorney. During that time he confessed to the rape, a confession he claimed was forced. He was found guilty and sentenced to death, a sentence to be carried out on January 7, 1946.

McGee’s original conviction was later overturned, at a second trial he was again convicted and sentenced to death. This too would be overturned because of prejudice in jury selection. Meanwhile, McGee’s case captured the attention of William Patterson and the Civil Rights Congress (CRC), as well as other communists and fellow travelers. In a case reminiscent of the Scottsboro Boys from the Depression years, activists were desperate to try and save McGee from the electric chair. His case would drag on for three more years with future Congresswoman Bella Abzug as his defense attorney. During these years the CRC, under Patterson’s leadership, along with communists and fellow travelers worked desperately to secure McGee’s release. The flurry of newspaper accounts in the communist Daily Worker, Paul Robeson’s Freedom, and other organs of the left-wing press in the days before McGee’s execution reveal the very real fear that the state was going to murder McGee. Unfortunately, despite all efforts, McGee was killed by electric chair on May 8, 1951. That day, Patterson was protesting the execution at the White House and a group of unionists and veterans chained themselves to the Lincoln Memorial in protest.

The Daily Worker devoted its next day’s cover page entirely to the case with a blaring headline that read “AVENGE MCGEE RALLIES TO RIGHT LYNCH SYSTEM” 1 The paper reported that McGee and Hawkins were having a consensual affair, something McGee told police shortly after his arrest and something that was never used in any of his trials. On the cover of the June 1951 edition of Freedom, Shirley Graham Du Bois wrote an article titled “Oh no brother, no one is going to forget about Willie McGee.” She wrote that McGee was not dead, he was just planted in the Mississippi soil, never to be forgotten because things would never be the same again. It was Hawkins who broke the southern cardinal rule against interracial sex, it was Hawkins who aggressively pursued McGee. McGee told a reporter in his death cell right before execution that he did all he could to avoid Hawkins, even leaving town. Graham Du Bois reminded readers that McGee was now buried in the soils, but where he was buried new things would grow, a new resistance to lynch law.

Poet and author Lorraine Hansberry was active in the campaign to free McGee. Her biographer Imani Perry argued that after he was executed, his death “haunted her pen.” In her poem “Lynchsong” written to honor Rosa Lee Ingram then on trial with her sons for killing her attempted rapist, she invokes the killing of McGee and the larger issue of lynch law. In the poem she “Sees the eyes of Willie McGee” in the “legal” executions in Laurel, Mississippi as well as New York City. The poem reveals the haunting that Perry referred to, with each case lost, another life was lost to a racist legal system and the surviving activists carried that weight with them to each new campaign.

Beulah Richardson’s poem “A Black Woman Speaks . . . of White Womanhood, of White Supremacy, of Peace” was inspired by the execution and by speaking with McGee’s widow Rosalie. The poem is a powerful rejoinder to a white womanhood that was often at the heart of lynch law. As in McGee’s case, it was a white woman who accused rape, perhaps to cover her own infidelity. But she used the power of her whiteness and gender to unleash the legal system on a man who jilted her. Dayo Gore argues that it was this poem that made Richardson a powerful artistic voice among the Cold War Black Left and Erik McDuffie claims that it was one of the inspirations for the founding of the Sojourners for Truth and Justice. This poem solidified Richardson’s artistic talents and her centrality to the Cold War Black Freedom Movement.

The poem opened with Richardson noting that it was right for her to speak of white womanhood because her fathers, brothers, sons, and husbands died for it. The poem addressed the weaponization of white womanhood in racist legal institutions that policed Black bodies to preserve white ones. She noted something so few acknowledged then and just as often today, that white women invested as deeply in their racial identity as white men, though they secured far fewer returns. The poem described the slave trade and the trade in Black women and likened it to the sexual trade in white marriages. Richardson uses striking imagery to link women’s oppression and the “difference in degree.” Black women’s slavery, she wrote, was involuntary, while white women agreed to their own and were convinced to see Black people as their enemy, convinced that whiteness had its own dividends. But they shared the same enslaver and should white women recognize that, it would lead to revolutionary change.

Richardson’s call for unity was reflected in her larger belief that capitalism secured its vice grip over working people by ensuring racial division; to awaken all oppressed people to their common enemy would be a revolutionary act. Her sorrow in losing McGee was palpable in the lines of her poem as the pain of losing another Black man to a white woman’s accusations was all the more painful in knowing that there were larger forces invested in white supremacy. As she asks in another one of her poems “has white supremacy ended your poverty, your pain, your misery?” Richardson described white supremacy as an investment in one’s own poverty, material and spiritual poverty.

William Patterson’s work on the McGee case happened just as he and other Black activists were facing their own legal issues because of Cold War repression and their links to the Communist Party. Because of the CRC and Patterson’s involvement in McGee’s defense, the State Department monitored the case closely and those involved in it. Gerald Horne has noted that local whites in Mississippi were reportedly more than happy to deny McGee his freedom and eventually his life, not because of his guilt, but because of the visible presence of communists in his case. Upon his execution, Patterson lamented that the “moral conscience” of white America had not yet been awakened to the dangers of lynch law. Patterson called the McGee case one of the most “historic acts of the last 80 years,” and it would be included in the CRC’s We Charge Genocide petition that accused the United States government in the genocide of Black America via lynch law, racist violence, and economic and legal policies.

On the one-year anniversary of the McGee execution, the Communist Party held a memorial. Speakers included his widow Rosalie, his attorney Bella Abzug, and Communist leader Claudia Jones herself immersed in legal battles. The memorial announcement described McGee as “one more” man sacrificed on the “blood-soaked” altar of the “white supremacy system.” His execution “shocked the civilized world” and he died because his “lynchers” could not admit the truth, that his only crime was being a Black man in America. 2 This case and others before and since revealed for Black freedom activists that the judicial system was directly linked to white supremacy. Though the courts were racist institutions, it was the active participation of white people that secured “lynch law” and maintained white supremacy. It was a hard lesson for activists that sought working-class unity against capitalist forces, and activists who preached the liberation of all people. But as Beulah Richardson and others wrote, white supremacy was a powerful tool that secured privilege but would never ensure material or spiritual security for anyone, Black or white.

Black men were not only accused of rape, they were raped by white women who used work within the home as a way to have access to their bodies. Similar to the rape of Jeremiah Reeves, Willie McGee was a victim of rape and sexual assault by Wiletta Hawkins. I have published an article on this case:

“He’s a Rapist, Even when He’s Not: Richard Wright’s Man of All Work as an

Analysis of the Rape of Willie McGee,” The Political Companion to Richard Wright, eds. Jane

Gordon and Cyrus Ernesto Zirakzadeh (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2018), 132-154