Contesting State Violence in and Beyond the Archive

This week we’re revisiting Heather Ann Thompson’s Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy (Pantheon Books, 2016). Today we are featuring an essay by Dan Berger.

Let me begin by stating the obvious: Blood in the Water is an excellent book, one that validates the historical profession on nearly every level. Thompson mines a dramatic array of archives with meticulous detail to recreate what happened in a pivotal series of historical events. She marshals her evidence with stunning clarity to produce an eminently readable narrative that speaks to a host of urgent concerns. And in an era where some of our conservative colleagues still bemoan that attention to subaltern subjects is either substantively irrelevant or intellectually dangerous. Thompson shows convincingly that a Black-led, multiracial prisoner rebellion is one of the most significant events in recent history. Period. Blood in the Water is an impeccable blend of legal, political, and social history. And it is a gripping tale, told with clarity, empathy, and restrained outrage. It will be a touchstone in carceral history for scholars, journalists, activists, and at some point, perhaps even movie-goers, for the foreseeable future.

Blood in the Water offers many avenues for analysis. Here I want to examine what the book suggests about researching and writing the recent history of the carceral state. Much as the Attica rebellion was itself a turning point in a larger American story of racist punishment and antiracist resistance, so too is Blood in the Water a turning point in the historiography of those dynamics. It therefore provides an opportunity to examine the methodological and political stakes of conducting a critical history of prisons in a country so defined by them. Though Thompson discovers infuriating new details about the scope of such plans, the intent has been plain for all who care to see. All it required was the willingness to see state violence for what it was—and for what it always is: a disproportionate display of violence enacted upon the most marginalized sectors of society for the purposes of solidifying the state’s monopoly of force.

And that is where the Attica story gets hard. The government initially claimed that prisoners had killed ten hostages and castrated others during the rebellion. Even after that lie was revealed the next day, many who heard news of that state violence still blamed the men in Attica, directly or indirectly. Attica is as clear an example as any that violence is both physical and interpretive. The carceral state shapes our definition of what the archive is, and who or what we think of as legitimate sources. In taking prisoners and their stories seriously, Thompson and the larger field of carceral history contest the state’s archival violence. Certainly, the government tried to secure this silence. As with any dedicated cover-up, Attica presents numerous challenges to accessing reliable sources. That challenge is exacerbated by the problem of studying state violence generally and prisons in particular. Records are well-hidden, shredded early and often, or not kept at all. Even a cursory scan of Thompson’s footnotes reveals the heroic task of accessing the materials documenting the intentional murderous violence by police in retaking Attica prison on September 13, 1971, as well as the decades of subsequent duplicity.

Most importantly, Thompson shows why historians need to rethink the boundaries of what we consider archives to be. Blood in the Water demonstrates the extent that archives themselves are sources of struggle and contestation. And more than access, that struggle concerns the problem of recognition. The first step toward approaching archival research is the recognition of historical significance. Scholars still need to reckon with W.E.B. Du Bois’s contention, first raised about Reconstruction but relevant to any attempt at subaltern governance, about the conceptual violence enabled by the “propaganda of history.” Before there are artifacts, there is ideology. Simply put, we have to take seriously that people in prison and their friends and family members are political actors, with ideas and strategies and political will.

Reconsidering the archive brings up questions of scale. Thompson shows us, albeit implicitly, that Attica was everywhere. The range of archives consulted and the cast of characters involved reveals how central the prison movement was to journalists, state and national politicians, unions, social movements, and others. This shifts the geography of where we understand prisons to be. Attica is a prison in Western New York, a series of jail rebellions in New York City, a defense committee in Chicago or Berkeley, a protest in San Quentin or Alderson, a meeting in Wounded Knee or Washington D.C., and a phone call between insurance brokers and broken-hearted widows. Attica means different things in those places, yet it exists in all of them. Recognizing its ubiquity, prisoner advocates declared that “Attica is all of us.” The prison movement recognized that it, and the Black Power movement to which it was so closely tied, exhibited a universal freedom impulse. To that, we could add that Attica is everywhere.

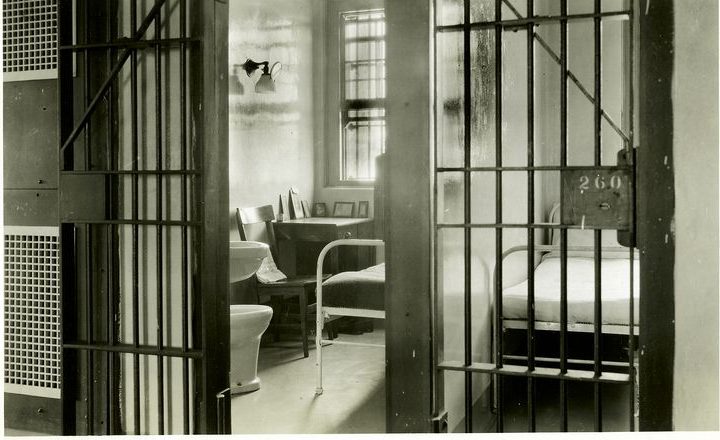

Attica was everywhere because the dialectics of repression and resistance were everywhere. American prisons in the 1970s were undergoing a crisis of legitimacy. Even if the scale of Attica was more dramatic, the underlying dynamics remained consistent across the country. The rebellion was remarkably typical when it first erupted. The same mix of spontaneity, planned organizing, frustration, overcrowding, self-education, medical neglect, and physical abuse could be found in San Quentin and Bedford Hills, Angola and Alderson, Marion and Graterford, and other prisons around the country. Yet the scale of state violence at Attica can paradoxically isolate Attica from the larger prison landscape of which it was a part. Much as the Black Panther Party often stands in for a broader set of political approaches to Black radicalism in the late 1960s, so too can the Attica uprising hold too much weight in popular memory of that pivotal moment in time. “Attica” risks taking the place of a multisited prison movement, both within New York and across the country (and, in fact, across the world). The incredible depth of Blood in the Water should motivate us to recover the breadth of opposition to American prisons as well. It should remind us of the long arc that accompanied prison rebellions. That arc helps explain why the United States makes such widespread use of solitary confinement and such limited use of clemency, such long sentences with such pecuniary retributions.

Prisons, as Thompson notes in her epilogue, got better and worse after Attica. Prisoners secured more legal protections for certain forms of free speech and religious liberties, but the law also increased the use of solitary confinement and institutionalized an expansive set of civil, legal, political, and social exclusions, each backed by routine physical violence. Yet the severity of abuses that led up to the Attica uprising and dozens of other rebellions in that time period illustrate how bad prisons already were. The new modes of violence that accompany modern prisons are deeply embedded in the structure of prison itself. As prisons require us to retrain our sense of archives, so too do they demand that we reckon with the sexualized racism of American state violence.

That reckoning asks us to probe the limits of empathy. It is an article of faith within critical prison studies and the emerging subfield of carceral history that currently and formerly incarcerated people are political actors. Our work necessarily challenges the foreclosure of consideration that many scholars, journalists, pundits and others evince when it comes to prisoners. So our work is already pushing the boundaries of empathy. Yet Thompson goes further in detailing the struggle of correctional officers and their families to secure justice from the state for the horrors they endured in 1971. It is a vital component of the story and should encourage other historians to study guards and prisoners together. But it also raises questions about whether their shared mistreatment extends to shared grievances or shared means of redress.

Like the response to welfare liberalism, the crisis of carceral liberalism in the 1970s broke hard-right. What Thompson calls the “politics of the ironic” (567-568) was in fact the acceleration of a dangerous right-wing populism that, especially through police and prison guard unions, continues to mobilize for greater repression. How might we balance empathy for all aggrieved parties while recognizing that trauma and social location can lead as much to revanchist notions of justice as reparative ones?

Finally, then, reckoning with state violence begs the moral and historiographical question about the nature of justice itself. What would it mean for the Attica Brothers, or the hostages and their family members, to get “justice”? That they did not achieve justice is clear, and Thompson lays out the reasons why. Like the response to urban rebellions, the response to prison uprisings demonstrated the failures of liberalism. In moments of crisis American liberalism sought to vanquish the left, cover its tracks, and retreat to proceduralism. But what does justice look like for survivors of state violence? And how do we record a history of alternate forms justice? I do not know the answer, but it seems clear that it demands us, as historians and as human beings, to examine radically illiberal modes of governance and accountability. The 2016 national prison strikes—begun on the 45th anniversary of the Attica rebellion, which lasted for several weeks—together with the anti-policing protests most identified with the Black Lives Matter movement, and the diverse demands for reparations demonstrate that we will be asking these questions for some time to come.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for this commentary and for your work more generally.

You speak of conservative scholars deriding as dangerous or irrelevant explorations of neglected, marginalized, subaltern peoples. Could you point me to some examples? I’d like to see what they say and how they justify what they say.

Thanks again.