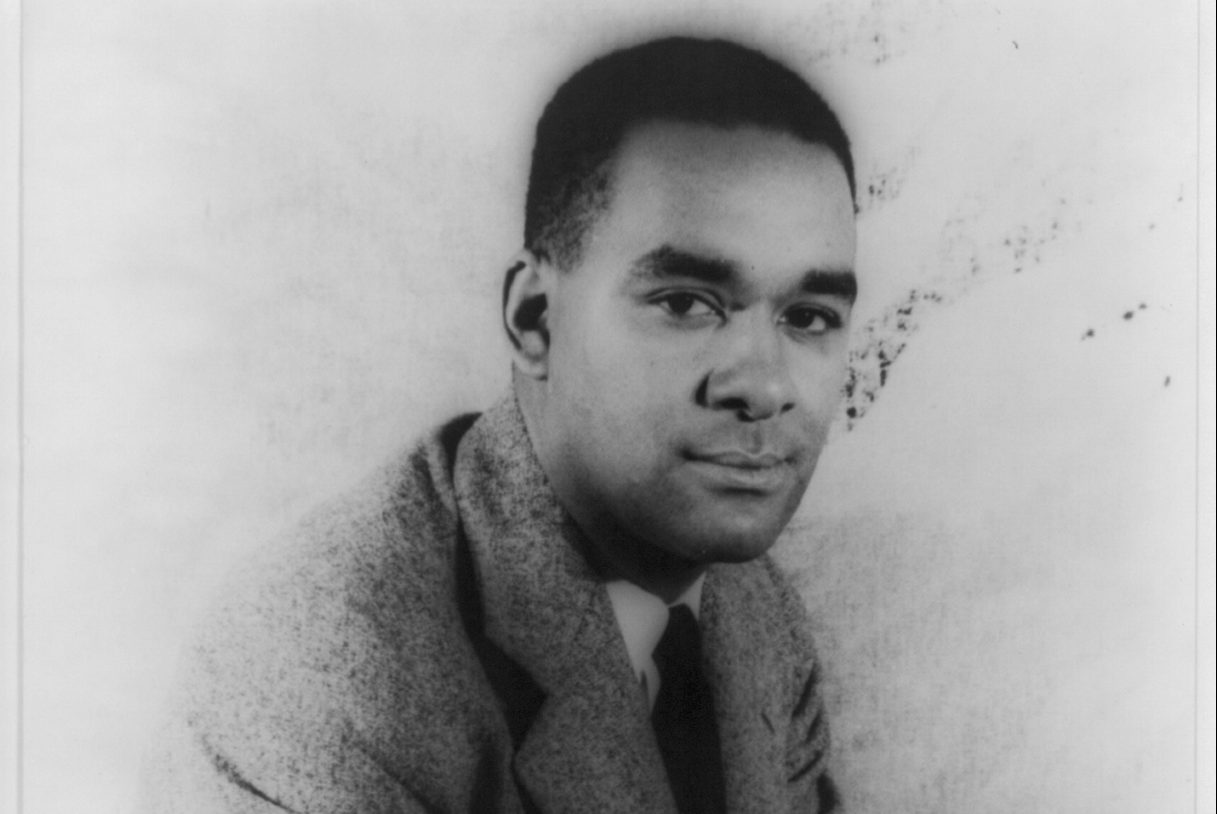

On Richard Wright’s Hunger and Kiese Laymon’s Heavy

Richard Wright’s famous autobiography, Black Boy: A Record of Childhood and Youth (1945) was originally titled American Hunger. However, the memoir got cut in half, stopping right before Wright left the South for Chicago. The original full version was not published until 1991 by Library of America. Wright hoped the full volume would force his audience to focus on not just Black southern life, but the deeper issues that Black southern life revealed about the nation. One major national theme he wanted to address was hunger. What did his physical hunger as a young Black boy in Mississippi reveal about the larger spiritual malnourishment of the nation?

Reflecting on how the scarcity he had faced as a child had disqualified him for the physical requirements of a job as a postal clerk, he writes: “I felt that it was unfair that my lack of a few pounds of flesh should deprive me of a chance at a good job.” Wright then makes the move of connecting that loss to a greater American problem: “my losing was only another manifestation of that queer, material way of American living that computed everything in terms of the concrete: weight, color, race, fur coats, radios, electric refrigerators, cars, money… It seemed that I simply could not fit into a materialistic life.”

Fourteen years after Wright’s death, another prodigious Black male writer from Mississippi was born: Kiese Laymon. His latest book, Heavy: An American Memoir (2018) is in direct conversation with Wright – along with other famous Mississippi and African American writers such as Eudora Welty, William Faulkner, Toni Cade Bambara, and Margaret Walker. In fact, in Heavy, Laymon recalls reading and re-reading Richard Wright’s Black Boy in college; it felt like a “call to arms … a warm whisper.” He appreciated how Wright used words as weapons and “wanted to fight like Wright. I wanted to craft sentences that styled on white folk.” Nonetheless, he is also critical of Wright. Though he understands why Wright left Jackson, Mississippi, Laymon’s hometown, Laymon wishes Wright would have come back like Laymon’s Grandma – and Laymon himself. Laymon imagines what Wright’s works would have looked like had he returned: “I wondered if Black children would have laughed, or smiled more at his sentences if he imagined Mississippi as home. I wondered if he thought he’d come back home soon the day he left for Chicago.”

Both memoirs have striking similarities and differences that Laymon invites his readers to consider. Both Wright and Laymon have conflicting relationships with their mothers. Wright’s mother discouraged him from reading and writing. Laymon’s mother, on the other hand, was a professor of political science at Jackson State University and raised Kiese to be excellent at both reading and writing. Interestingly enough, despite the starkly opposite upbringings, both Laymon and Wright were scarred from their mother’s abuse. While Wright was nearly beaten to death for accidentally setting his house on fire at the young age of four, Laymon was beaten numerous times throughout his childhood and youth for metaphorical fires his mother felt he set for dating a white girl in high school, or questioning his mother’s own dating choices.

Laymon knew the same hunger as Wright. In Heavy, Laymon writes: “At our house, there was no pantry. There was hardly any food other than spoiled pimento cheese, the backs of molded wheat bread, a half-empty box of wine, and swollen green olives.” The deprivation led him to ponder on stealing all the food from the “rich-white folk houses” his grandma cleaned for.

Both Wright and Laymon assuaged their hunger in different ways. Wright ate excessively to gain weight for the job at the post office, while Laymon overate in response to his relationship with his mother. In one of the most moving pieces of Laymon’s memoir, he binge-eats after hearing his mother having sex with a Black male leader in Jackson that he despises and does not trust. He writes:

I hated my body. I walked in the kitchen, got the biggest spoon I could find, and dipped it halfway in the peanut butter and pear preserves Grandma had given us. I heard the wailing all the way in the kitchen. I dipped the same spoon a quarter deep into Grandma’s pear preserves and put the whole spoon in my mouth. I did it again and again until the jar of peanut butter was gone. The wailing didn’t stop. I hated my body.

In a striking interview at the Chicago Humanities Festival Interview, Laymon discusses what makes his memoir different from others that came before it. He admits that, like Wright, he “was taught to use words to talk about what white folks were doing to us.” However, he states that he was not taught to use words to talk about those secrets that “metastasize and harm and grow and harm and grow.” For Laymon, “all of those secrets were tied to body, tied to wetness, particular kinds of wetness in the body – be it sexual, be it overexertion. And I just really wanted to write a book where I explored some of that wetness, some of that black body-ness, some of that Mississippi-ness that I had just never seen explored extensively on the page.”

I was struck by that bold claim. Laymon admits in Heavy that he read Black Boy numerous times, but he does not mention American Hunger. I assume he has read it, and I have been wrestling with just how different it is from Heavy. Had that wetness and Mississippi-ness related to the Black body really never been explored extensively on the page? After overeating, Laymon admits to “hating [his] body,” and Wright – after drinking “two quarts of buttermilk” and downing “six bananas” in an attempt to gain weight to qualify for the post office job – admits to sitting “alone in [his] back room hating [him]self.” Later on in American Hunger, Wright admits to overeating again: “I ate when I did not want to eat, drank milk when it sickened me. Slowly my starved body responded to food and overcame the lean years of Mississippi, Arkansas and Tennessee, counteracting the flesh-sapping anxiety of fear-filled days… I made eating an obsession.”

One could easily argue that both books explore self-loathing Southern Black boys who become men as they quietly navigate coming to terms with their bodies and their relationship with their single mothers. Both books are about what the “weight” that hunger reveals about them and the nation. However, with all the commonalities between the two books, I agree with Laymon: his book does explore that Mississippi-ness and wetness in an unprecedented way – at a level that Wright failed to reach. Unlike Wright’s perfectly chronological memoir, Laymon bends time and tenses as he switches from the past to the present, and even stretches into the future. Laymon’s work registers in the meta key. The full “original” version of American Hunger is a beautiful memoir – one of my personal favorites. However, it does not reinvent the genre; for the most part, it works within it to tell a successful story about how a poor Black boy from rural Mississippi became one of the greatest writers to ever live. There are moments of brutal honesty, such as when he discusses binge-eating, the struggles to find jobs, and the struggles to connect with people in his family and the Communist party, but the general thrust of the narrative is one of steady ascension to worldwide success.

Laymon does not let his reader off that easy. In fact, Laymon is not even writing the book to the “general reader,” but to his mother. The general arc is not ascension to success; it is the crazy ebbs and flows of life that lead a Black boy from Jackson, Mississippi to soar to over 300 pounds as a teenager, then, through fanatical levels of exercise and starvation, back down to 170 – only to relapse to 300 pounds again while battling a gambling addiction. It is about a man who saw his mother gamble much of her earnings away, who then became that same gambling addict, who then promised to stop, but then ultimately failed to live up to his promise and gambled again.

Laymon never gives the reader resolve, but neither does life. Laymon reinvents the genre with his honest attempt at reflecting that constant struggle. He writes in the first pages of the book that he wanted to write an American memoir that lied and did that “old black work of pandering and lying to folk who pay us to pander and lie to them every day.” In fact, Laymon’s original plan was to write a traditional weight-loss book. He wanted to “end the book with acerbic warnings to us fat Black folk in the Deep South” to lose weight and do better, like he did when he lost weight. In the end, he chose to write a more honest book in which he condemns the main character: his own body. As readers observe this self-interrogation, the nation is indicted as well. Hopefully, it will lead other folks to perform the same honest self-interrogation; it may very well be the only way for the nation to heal the many open wounds still harming it.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.