Notes from the Library: Black Nativity

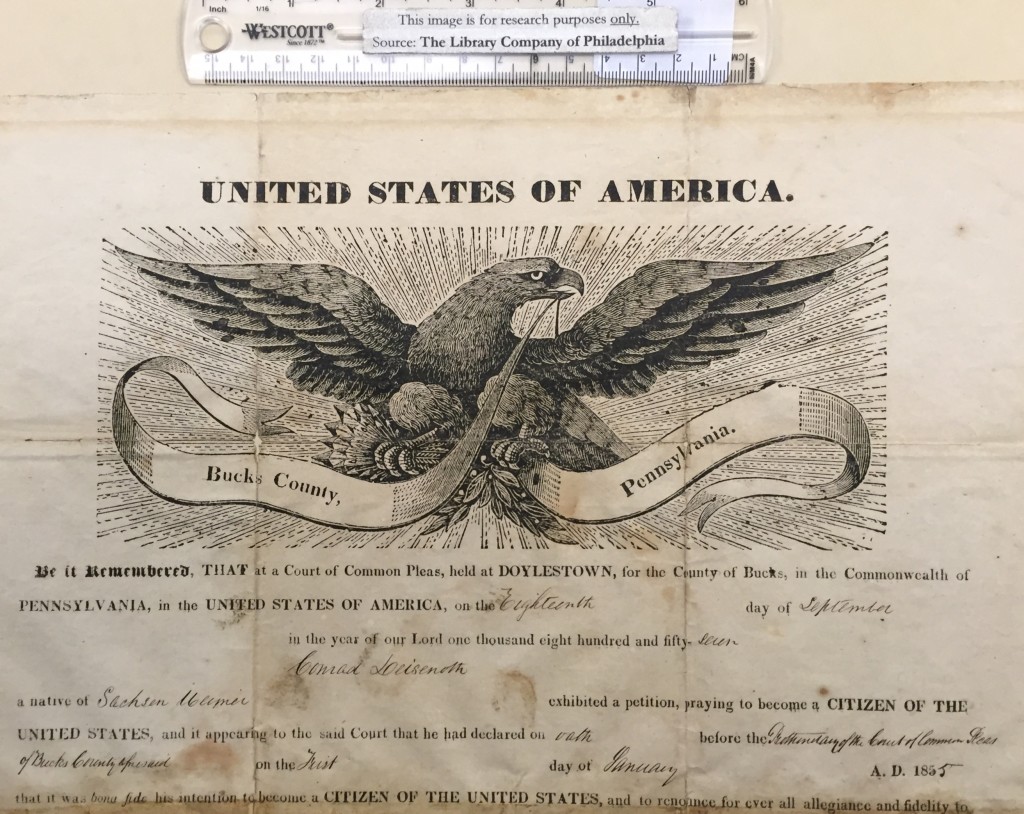

On September 18, 1857, Conrad Deisenoth became a citizen of the United States. This print, held at the Library Company of Philadelphia, sketches Conrad’s life to that point. Born in Saxe-Weimar, a duchy in what is today the central German state of Thuringia, Conrad came to the United States no later than January 1850 and settled in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he decided to petition for citizenship. Beyond that, the certificate asks us to imagine his story. What did Conrad do between January 1855, when he filed the petition, and September 1857, when it was granted? Did he wait anxiously, or did he forget his uncertain status while he went about his daily life? Did he celebrate when he received the certificate? Did he feel relief that the wait was over, or anger that it had been so long? Did he consider the cost of a frame for the fourteen-by-sixteen print, imagining a wall in his home where it might hang? Or did he fold it up and tuck it away, all but forgotten in a drawer or a trunk? Did citizenship change Conrad’s life? And what did his naturalization mean to other Pennsylvanians, or to other American citizens? This broadside opens up histories of immigration and naturalization and the politics of citizenship in the nineteenth century. The certificate is a testament to the value of belonging—legally and socially—in the United States, as well as to the nation’s historically constrained paths to inclusion.

The specifics of the certificate stand out given the vagueness of Conrad’s path to citizenship. We know not only where he was born, but also that he renounced fealty to Charles, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar, ruler of a set of territories with an area slightly larger than that of Rhode Island. But rejecting the tiny state of his birth was only the first in a series of hurdles on the path to naturalization. The court had to be convinced that Conrad “had behaved as a man of good moral character.” Further, he had to show himself “well disposed to the good order and happiness” of the nation. These standards, along with the formality of the document, suggest the importance American lawmakers attached to citizen status. By the same token, Conrad’s choice to file the petition and the fact that he met these standards convey his sense of the value of a formal attachment to the nation. Conrad Deisenoth changed his life in exchange for this certificate of citizenship.

Pennsylvania’s 1838 constitution made citizen status a prerequisite for voting, which might explain why Conrad filed his petition. That same clause limited the franchise to white freemen, which explains how a certain segment of the American population might have responded to Conrad’s citizenship. In the antebellum period, black activists were outraged that immigrants could secure privileges from which they were barred. The summer of 1849 found black Bostonians fighting for equal access to public schools. On a July evening, activists drafted a message to the mayor explaining that it was “rather annoying” that “foreigners of all kinds” could access the common schools while black Americans remained excluded. “It is with feelings of amazement that we witness Englishmen, Frenchmen, Irishmen, Germans, Scotchmen, and others, in our community, who enjoy all the local privileges . . . [while] we are shut out from the institutions of learning in the land of our nativity.” Black Philadelphians expressed similar sentiments in 1855, the same year Conrad Deisenoth took his oath of naturalization, as they petitioned state legislators for the right to vote. They noted that they had suffered violence at the hands of mobs composed largely of European immigrants, and they rooted that violence in legal inequalities. Rioters, they said, bought into American racism because they were “candidates for those privileges of which we are debarred.” The black petitioners were descendants of men who had fought to create the nation, and they sought “rights purchased by our loyalty and by the blood of our fathers.” “We are native Americans, and since allegiance is due from us,” they reasoned, “protection and equal rights are due from the Government.”

These critiques were less about attacking immigration than they were about highlighting a particularly egregious kind of injustice. Still, there’s a hint of prejudice here, a sense that the injustice is so egregious because “foreigners of all kinds” are being favored over Americans. It’s a bit odd to reflect on the politics of marginalized people and see rhetoric that might marginalize others, whether intentionally or not. But it made sense for black activists to appeal to their Americanness, to make clear that they did not need to renounce other loyalties, to invoke patriotism and sacrifice on behalf of the still-young United States. It also made sense for these activists to feel their Americanness, to be emotionally connected to their native country, the place for which their fathers had died. This was the world in which Conrad Deisenoth became an American citizen and these were the politics surrounding his certificate. His oath of loyalty, his good moral character, and his dedication to the happiness of the nation all accrued political capital. African Americans pushed lawmakers to recognize that they had met the same standards, that they had earned the right to be included. Activists in Boston, Philadelphia, and across the free states struggled to secure fair terms of trade for black blood and black nativity.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Very important issues and documentation. Begs the question: “WHAT DO BOTH DEMOGRAPHY AND ‘ENCOURAGED IMMIGRATION’ REALLY MEAN IN A WHITE-SETTLER SOCIETY?” This is not only about the USA, but virtually *every* society in the Americas. I pose this question to the folks of AAIHS.