Frederick Douglass’s Radical Imagination

*This post is part of our online forum on the life of Frederick Douglass.

Often on Sunday afternoons, a teenage Frederick Douglass sat on the eastern banks of the Chesapeake Bay, where he watched dozens of ships sail past and dreamed about his freedom. “Sunday was my only leisure time,” Douglass wrote in his first autobiography. He spent much of that time recovering from a week of work and brutal discipline under Edward Covey, but he also chose to use some of his days doing important imaginative labor. He would walk to the water’s edge, look out at the mass of white sails, and speak to the ships. “You are loosed from your moorings, and are free; I am fast in my chains, and am a slave! . . . O that I were free! . . . O that I could also go!”

For Douglass, imagining himself on a boat as a free person was difficult, but it was critical for his efforts to escape bondage. Douglass lived under the watchful eyes and brutalizing hands of White southerners like Covey as well as a national legal system designed to keep Black people enslaved. Slavery was not a mental condition, and his hope alone could not emancipate him. But Douglass’s writing allows us to consider the history of his imagination: the ways he expressed optimism, the circumstances in which he envisioned a better future for himself, and the significance of hope and fear to his political projects. Douglass’s life and writings highlight the ways Black people have imagined different futures as a step toward changing their lives and the worlds in which they lived.

Douglass envisioned some of the specific contours of his freedom in the mid-1830s, when he was hiring his time as a ship caulker in Baltimore. He earned $1.50 each day doing that work. “I contracted for it; I earned it; it was paid to me,” Douglass noted. But at the end of each week, “I was compelled to deliver every cent of that money to Master Hugh [Auld]. . . solely because he had the power to compel me to give it up.” In between jobs, Douglass thought about freedom, imagining it in part as a material relation in which he had the right to the fruits of his labor.

He had attempted to run to freedom once before with a group of fellow slaves who together envisioned themselves as free men. In early 1835, Douglass began to discuss running North with a group of enslaved men who lived near him on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. As he later described it, “I bent myself to devising ways and means for our escape, and meanwhile strove . . . to impress them with the gross fraud and inhumanity of slavery.” But Douglass obscured the collective interpersonal work necessary to the plot. Douglass and his allies—Henry Harris, John Harris, Henry Bailey, and Charles Roberts—chose to have dangerous conversations about running away and talked one another through their anxieties. “We met often, and consulted frequently, and told our hopes and fears.” They despaired over the obstacles that stood in the way of freedom, but chose to continue hoping they could move toward liberation together. Meeting to discuss their visions of freedom helped motivate the men in its pursuit. Of course optimism alone would not liberate them. Before they could embark, the conspirators were arrested, interrogated, “dragged . . . fifteen miles behind horses” and held briefly in jail, until their owners decided to return the enslaved men to work.

Douglass successfully escaped slavery in 1838, after which he exploited White Americans’ anxieties about slavery and the nation’s future to further his antislavery work. In the Narrative, Douglass refused to offer details about his escape and criticized abolitionists who were vocal about the Underground Railroad. He wanted to leave slaveowners “profoundly ignorant” about the paths enslaved people traveled to freedom. “I would leave him to imagine himself surrounded by myriads of invisible tormentors,” Douglass wrote, “ever ready to snatch from his infernal grasp his trembling prey.” Similarly, he played on White northerners’ fears in his famous July 5, 1852 speech that questioned Independence Day celebrations in a nation of slaveholders. Douglass urged his audience to imagine the evil of slavery destroying the nation. “Be warned! a horrible reptile is coiled up in our nation’s bosom,” he threatened. “For the love of God, tearaway, and fling from you the hideous monster.” Douglass believed he needed to make White Americans envision the dangers slavery posed, in the present as well as the future, as a way to force them to confront the institution.

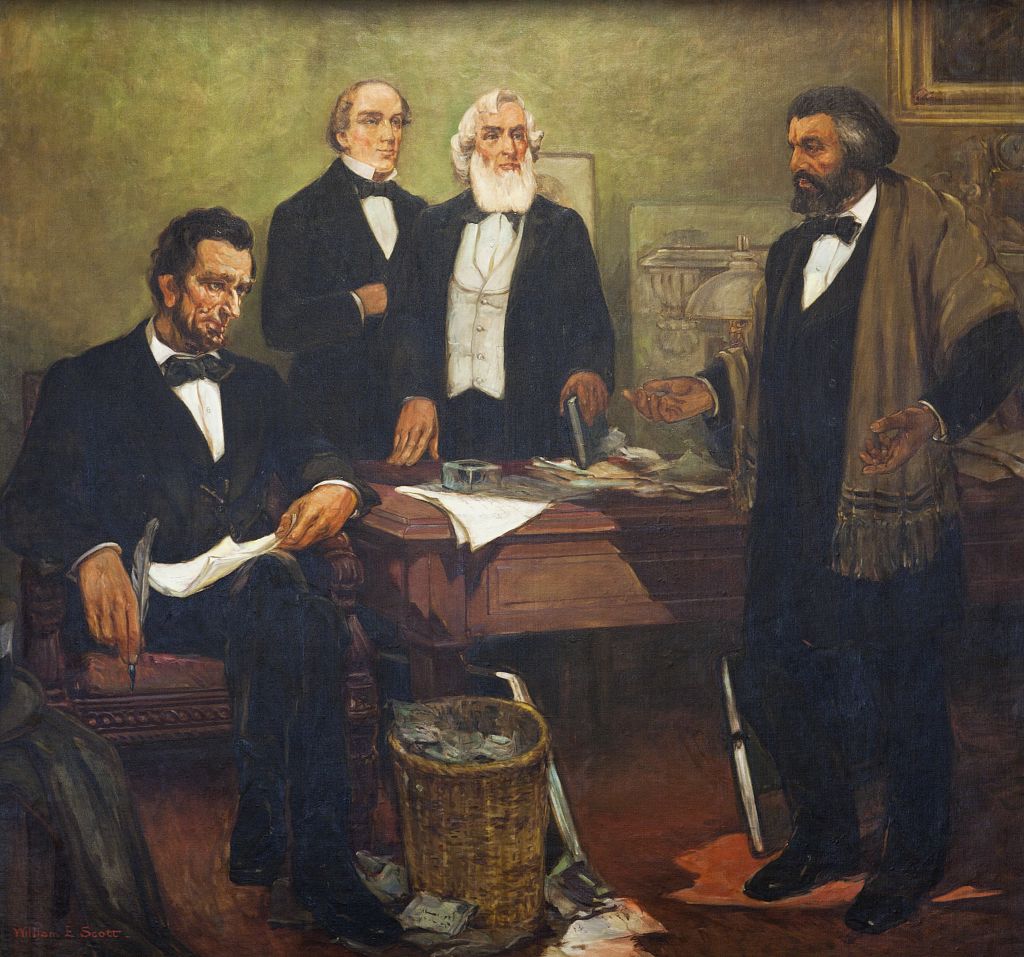

When White northerners did finally confront slaveowners, Douglass was well prepared to help people imagine the Civil War as a fight for Black liberation. He rejoiced at the outbreak of conflict. In July 1863, Douglass said, “once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S. . . . [and] there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”1 He pushed White Americans to imagine Black soldiers bearing arms nobly in defense of the republic, energizing the Union war effort. More radically, he connected that image directly to a redefined postwar legal status for African Americans. He rejected the argument Roger Taney had made in the Dred Scott case and challenged all others who denied that Black people were entitled to legal protections in the country. The words and ideas of activists like Douglass, added to the extensive labor Black men and women performed in Union camps, made possible the transformative legal reality of Black citizenship.

Beyond the national cataclysm of the 1860s, Douglass continued to anticipate new terms for Black life in the United States. On August 1, 1880, he spoke on the meaning and the limitations of Reconstruction. “Today,” he declared, “in most of the southern states, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments are virtually nullified.” The national government had failed to enforce the terms of those enactments, and had “left the former slave completely in the power of the old master.” Still, Douglass felt hopeful. “It is a great thing to have the supreme law of the land on the side of justice and liberty. It is the line up to which the nation is destined to march, the law to which the nation’s life must ultimately conform.” Douglass’s optimistic claims demanded that White lawmakers take steps to realize the legal order that the Constitution outlined, calling on government officials to do the work of moving toward justice.

Douglass’s work centered on imagining new lives for himself and for other Black Americans. Recent scholarship by Daina Berry, Elizabeth Pryor, and Tamara Walker has examined the power Black people exercised by thinking about themselves in ways that challenged the imperatives of those who bound them. These scholars explore hope and imagination as foundations for various forms of Black activism. Hope was not a natural response to bondage, but instead reflected a series of difficult choices made in the midst of calculated psychological abuse. Hope is hard, and it is worth considering how Douglass and other Black people came to feel it, express it, and contemplate its transformative possibilities despite the forbidding circumstances of their lives. When Douglass looked out over the Chesapeake Bay and dreamed of freedom, he did the powerful work of imagining a different kind of Black future.

- Frederick Douglass, “Negroes and the National War Effort,” July 6, 1863. ↩