Race and Music in Memphis

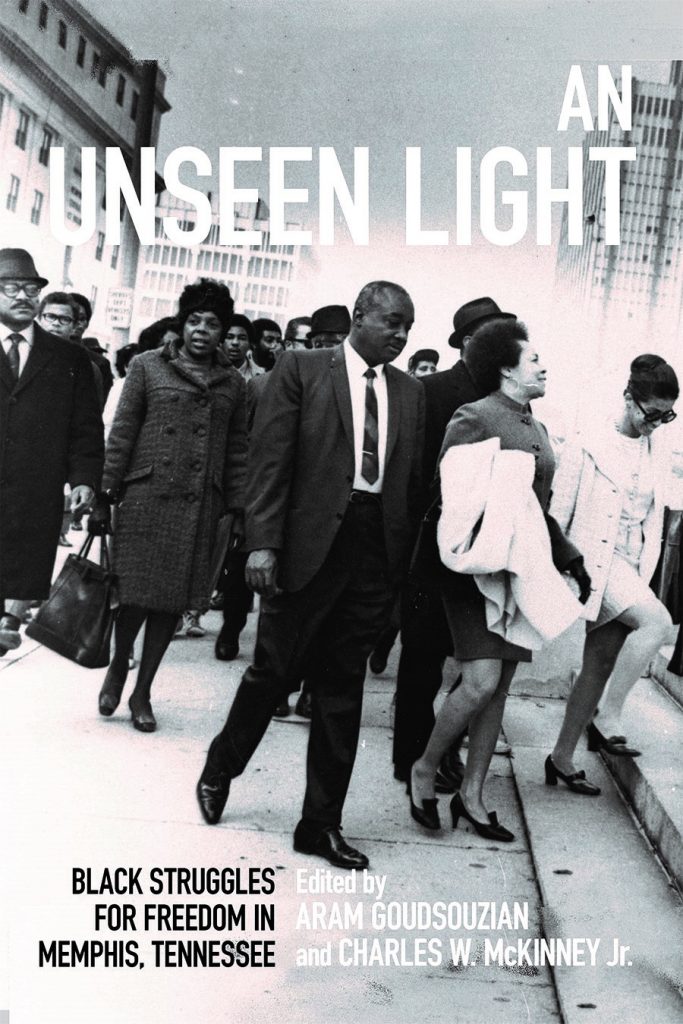

*This post is part of our online forum on Aram Goudsouzian and Charles McKinney’s An Unseen Light

In 1992, Rufus Thomas was interviewed by historians from the Smithsonian Institution about his lifetime of work in Memphis music. In this conversation, Thomas chronicled a career that stretched back to the 1920s and influenced nearly every major development in Memphis musical culture, from blues to rock ‘n’ roll to soul and beyond. Thomas’s list of accomplishments trace a century of musical history: he started out performing in Mississippi minstrel shows and Beale Street nightclubs, recorded the first hits on both Stax and Sun Records, served as a DJ on pioneering all-Black radio station WDIA, and recorded the first hits on groundbreaking labels Sun and Stax Records. His tenure at Stax was particularly notable, as he scored hits – from the strutting “Walking the Dog” to the bubbling “Do the Funky Chicken” – throughout the entirety of the label’s history. He’d even stolen the show at the celebratory 1973 Wattstax concert. His recordings reveal a tradition of Memphis sounds at their most playful and vibrant.

Thomas discussed all of this in conversation with the Smithsonian interviewers. He spoke of his accomplishments, honored his colleagues, praised his family and friends, and celebrated his city. Then, at the end, Thomas assessed his own role and hoped-for legacy.1 “You pay one hell of a price to be black,” he noted:

“But I am not going to die from it. I’m going to survive, and I’m going to live. And I’m going to do something recognizable, so when I pass off this land of the living…I will be remembered for what I have done – what I have done for the community, what I have done for my people, what I have done for the whole universe.”

Thomas’s poignant words here signaled a deeper theme that he revisited throughout his career. Throughout his life, particularly when reflecting on his work and legacy, Thomas paired remarkable stories of Black genius and community resilience with the hard realities of living and creating in a white-dominated society. He offered a particularly important intervention into the historical narrative of Memphis music itself, which is still often presented as a story of interracial progress and redemption from a racist past. Studios like Sun and Stax – and the rock ‘n’ roll or soul music that emerged from them – are offered as shorthand for the breakthroughs of the Civil Rights period, or even as interracial utopias where race didn’t matter or somehow didn’t even exist.

This narrative ignores a history that Rufus Thomas both shaped and expressed. Thomas resisted the inequities faced by Black musicians in Memphis, and he pushed back against the pernicious fictions of “colorblind” musical spaces and heroic whites that continue to taint larger understandings of the city’s cultural impact. His career demonstrates the local innovations that fueled the city’s global cultural impact and fostered its connections to the national fight for Black liberation. And his career signals the way that – through erasure and distortion – Memphis’s musical history has been weaponized as a vehicle for white-centered civic boosterism and nostalgic fantasias of the racial past. A full consideration of Thomas’s life and career – and a centering of his own words – forces a reframing of this history around a more accurate and complex picture.

Thomas’s career reveals the deep networks of Black labor that created the city’s musical flashpoints, as well as its connection to other traditions of Black resistance. He trained in high school and local nightclubs, where he joined a generation of Black musicians that he later promoted by hosting “Amateur Night” performances on Beale and his show on the pioneering radio station WDIA. The musicians with whom Thomas worked formed the core of Memphis’s musical revolutions, working in Black-controlled musical spaces that Thomas recognized and championed. As he put it, “Memphis’s amateurs are the world’s professionals.” He also saw the connections between Black music and other sectors of the fight for equal rights, from his early mentorship with activist educator Nat D. Williams to his marriage to Lorene Thomas, who served as Membership Secretary for the Memphis NAACP during its height of 1960s activity. Living and working within the South Memphis communities that fueled both musical and political revolutions, Thomas understood the possibilities and limitations of music as a force for progress.

These limitations shaped his career and structured his later recollections. He criticized the loss of economic opportunities and cultural autonomy that accompanied his treatment at both Sun Records – where producer Sam Phillips turned away from Black artists in favor of white artists like Elvis Presley who combined Black and white musical influences – and Stax Records, where Thomas felt mistreated at the hands of white collaborators who did not fully credit (or compensate) his role in defining the label’s sound during his decade run of hits. Asked to explain why this happened, Thomas – in reference to Stax mainstay Steve Cropper – said that Cropper “had that white thing that said because you’re black, you’re supposed to do exactly what this white man says.”2 As the sunny, white-centered narrative of Memphis music solidified in public memory, Thomas continued to push for greater recognition of Black creators as well as their cultural and political counterparts.

Despite his insistence on correcting the record, Thomas’s own words have largely been ignored in posthumous attempts to position him as a happy figure in the still-common story of Memphis music as site of interracial progress. When he died, for example, Tennessee Governor Don Sundquist eulogized Thomas as an “ambassador of unity” who “taught us not to see the world in black or white but in shades of blues.”3 But Thomas routinely refuted these simplified presentations throughout his career, and – through his life and career – provides us with a pivotal opportunity to enrich and expand our understandings. It is our obligation to honor him.

- Rufus Thomas, interviewed by Pete Daniel, David Less, and Charles McGovern, Memphis, 8/5/1992, 26, Rock ‘n’ Soul Video History Project Collection, Interviews, series 4, box 9, National Museum of American History, Archives Center, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC ↩

- Rufus Thomas, interviewed by David Less and Robert Palmer, Memphis, 1976, Civil Rights History Project Audio Collections, series 4, Mississippi Valley Collection, Preservation and Special Collections, University of Memphis ↩

- Bill Ellis, “‘Heaven’s Youngest Teenager’: Friends, Fans Pay Respects to Rufus Thomas,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, 12/21/2001, A1 ↩

Thank you for sharing this history so that we do not continue repeating the false narrative about Memphis music and racial harmony that persist to this day.

Wow