Revolution and Repression: A Framework for African American History

*Editor’s Note: This week we are publishing some of our favorite BP articles. We continue with this essay by blogger Brandon Byrd as part of our forum on Gerald Horne’s Radical History.

What are the defining themes of African American history? Scholars have considered this question since the advent of black historical writing in the nineteenth-century. Their answers have varied, ranging from slavery and freedom to migration to struggle and progress. But, at the heart of all of these responses, is the acknowledgement of the dichotomies that have defined the black experience in the United States. Movement has brought relief from and exposure to oppression. Victories have not come without loss. Amid pain, there has been pleasure.

While historians have most often provided their thematic frameworks for African American history in the form of sweeping narrative synthesis, Gerald Horne has chosen a different path. Over the course of his illustrious career, Horne has published more than thirty books exploring subjects including but not limited to race and racism, labor, black internationalism, politics, civil rights, entertainment, diplomatic relations, and war. He has neither spared any corner of the African Diaspora nor neglected any time period in his explorations of those subjects. Still, despite that daunting chronological, geographic, and topical scope, Horne has provided real coherence. In fact, taken together, his books provide a more potent and internationalist framework for African American history: revolution and repression.

Like struggle and progress, revolution and repression are intertwined. That has always been the case for African Americans. Even before the United States came into being, black people tried to overturn a social order built on European imperialism and African enslavement. They sought revolution, often by forging transnational allianceswith people and governments who either shared their interests or opposed those of their oppressors. Repression met those efforts. The architects and beneficiaries of the social order that black people and their allies opposed have often used violence, surveillance, political corruption, and the powers of the state to suppress revolution. They have waged war against it, fighting with some success and frustration against revolutionaries who dreamed enduring dreams of liberation for themselves and their world.

Horne’s Negro Comrades of the Crown: African Americans and the British Empire Fight the U.S. Before Emancipation (2012) demonstrates this relationship between revolution and repression. In the aftermath of what Horne has called the “Counter-Revolution of 1776,” the reactionary movement launched by the slaveholding founding fathers against the looming threat of an alliance of anti-slavery Britons and rebellious slaves, black people in North America continued to seek common cause with Great Britain and her subjects. Thanks to the work of Alan Taylor and others, some of this is now common knowledge among professional historians. Yet, what Horne reveals in more detail than his peers are the great depth, breadth, and impressive longevity of black engagement with the idea of British abolitionism. Over the course of the text (and in an astounding 136 pages of footnotes), Horne also shows that white Americans had deep-seated anxieties over potential Anglo-African solidarities right up to the U.S. Civil War. Those misgivings led to repression, not only against enslaved people but also against would-be British abolitionists accused of trying to unleash the “Horrors of St. Domingo” across America.

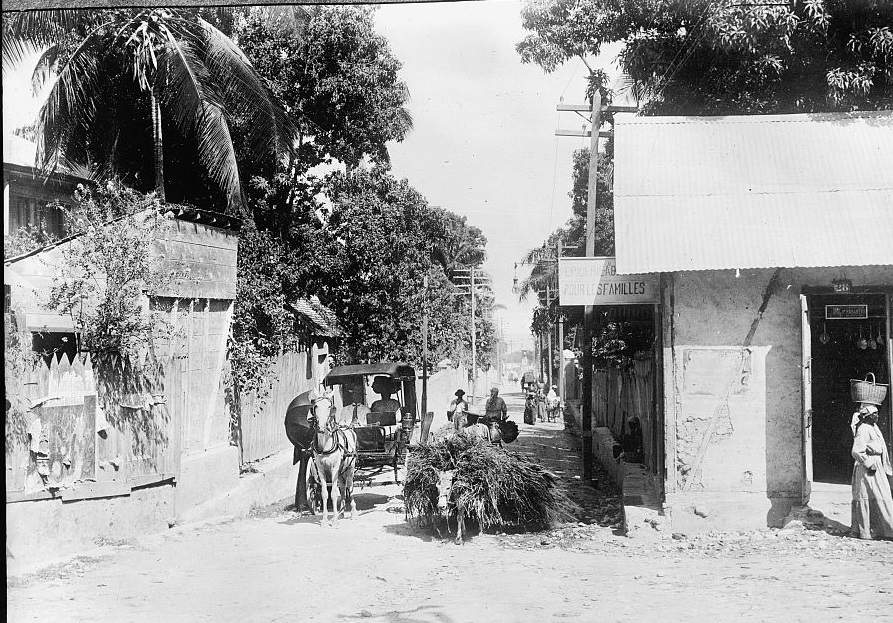

Although the panic of white planters does not quite prove that “the alliance between London and Africans within the republic was probably the most important threat to U.S. national security,” Horne does convince readers of the singular historical significance of the Haitian Revolution and Haiti. As Horne notes in Negro Comrades, the one successful slave rebellion in modern history and the Western Hemisphere’s lone nation-state governed by people of African descent mattered a great deal to Britons who (as Christopher Leslie Brown has established) advanced abolitionism out of self-interest and to white Americans wedded to slavery and white supremacy. They were never far from the minds of men like Ashbel Smith. In 1843, the diplomat from the Republic of Texas, a state birthed in pro-slavery revolution, wrote from London to U.S. Secretary of State John C. Calhoun. His primary purpose for writing was to express his sincere belief that Great Britain hoped “to make Texas a refuge for runaway slaves from the United States & eventually a Negro nation, a sort of Hayti on the continent [under] the protection of the British government.” For Smith, Great Britain was what a later generation of white southerners would call an outside agitator, a menace that could rile up otherwise complacent black people. Still, his letter revealed the undeniable power of Haiti, a nation that left little doubt about the potency of black resistance and the possibilities of revolution.

Horne advances this point in Confronting Black Jacobins: The United States, the Haitian Revolution, and the Origins of the Dominican Republic (2015). Building on the pioneering insights of nineteenth-century black writersand a wealth of scholarship that has exploded in recent decades, Horne confirms that Haiti and its people—Black Jacobins, in the appropriated, iconic words of C.L.R. James—became the bête noire of conservative white Americans and the example of black self-determination and anti-slavery revolution for African Americans. These trends not only affected antebellum U.S. politics and foreign policy (most notably in the U.S. government’s refusal to grant diplomatic recognition to Haiti) but also shaped relations among the United States, its black citizens, and Hispaniola in the aftermath of the U.S. Civil War. In his most significant contribution, Horne shows the tremendous effect that U.S. imperialism had on stifling what might have been revolutionary, post-emancipation solidarities. During the 1860s and 1870s, the United States tried to repress Haiti by encouraging the racialized formation of Santo Domingo, a country whose leaders accentuated their European heritage, and extended basic citizenship rights to African Americans. That many black people accepted that alluring offer, often overlooking or even supporting the acceleration of U.S. encroachments in the Caribbean, highlights the real obstacles facing potential black internationalists of that era.

Or, really, any period. In the twentieth-century, new modes of transnational political solidarities forged in opposition to colonialism and white imperialism emerged. But so did new forms of state-sponsored repression meant to stifle those revolutionary impulses.

In Red Seas: Ferdinand Smith and Radical Black Sailors in the United States and Jamaica (2005), Horne recovers the life and work of Smith, a Jamaican migrant-laborer who helped found the U.S.-based National Maritime Union (NMU). Under Smith’s leadership the NMU represented more than 90,000 maritime workers, many of them black, at its height during the 1940s. That Smith, an international labor activist who worked in Panama and Cuba before arriving in the United States, led this shining example of labor unionism was neither an accident nor surprising. Furthering the work that Marcus Rediker, Peter Linebaugh, W. Jeffrey Bolster, and Julius Scott have done on black sailors in the Age of Revolution, Horne shows that maritime travel continued to be a conduit for black radicalism well into the twentieth-century.

It is equally unsurprising that the U.S. government treated Smith like his more famous compatriot Marcus Garvey, placing him under surveillance and ultimately deporting him from the United States. By the time of that expulsion in 1948, anti-communism was the prevailing ethos of U.S. foreign policy. The attendant crackdown affected leftists in the United States and overseas, alike. It had an especially pronounced effect on black revolutionaries who continued to envision a world free from what historian Cedric Robinson would later call racial capitalism.

For Horne, that Cold War-era repression fundamentally re-shaped the expressions and sites of twentieth-century black resistance. In Cold War in a Hot Zone: The United States Confronts Labor and Independence Struggles in the British West Indies (2007), Horne argues that two factors motivated the U.S. government’s post-World War II interest in the Anglophone Caribbean: fear that the Caribbean would pursue a policy of non-alignment during the Cold War and anxiety that leftist politics and labor activism in the region would spread to the United States and undermine its racial caste system. The effects of those concerns were predictable. Although questions still remain about the centrality of the Anglophone Caribbean to U.S. strategists, Horne shows that U.S. intervention played a decisive role in empowering authoritarian and neo-colonial governments in the region while enticing African Americans to prioritize liberal reforms rather than leftist transformations. The latter point is crucial, especially when taken alongside the interventions of Mary L. Dudziak, Brenda Gayle Plummer, Carol Anderson, Penny Von Eschen, Kevin Gaines, Nikhil Pal Singh and others who have uncovered the extent to which anti-communism limited twentieth-century civil rights activism.

The history captured in these books continues today. As Horne notes in his recent reflections on the “just and righteous demands” of the Movement for Black Lives, we are part of a momentous period in African American history. In the face of extreme state-violence and surveillance, black and anti-racist activists built a global movement for social justice. While those activists work to dismantle the status quo, a new president promises more of the same.

Revolution and repression, repression and revolution. A framework for black history, past and still unfolding.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.