The Promise of the Nation of Islam

This post is part of our online roundtable on Ula Taylor’s The Promise of Patriarchy

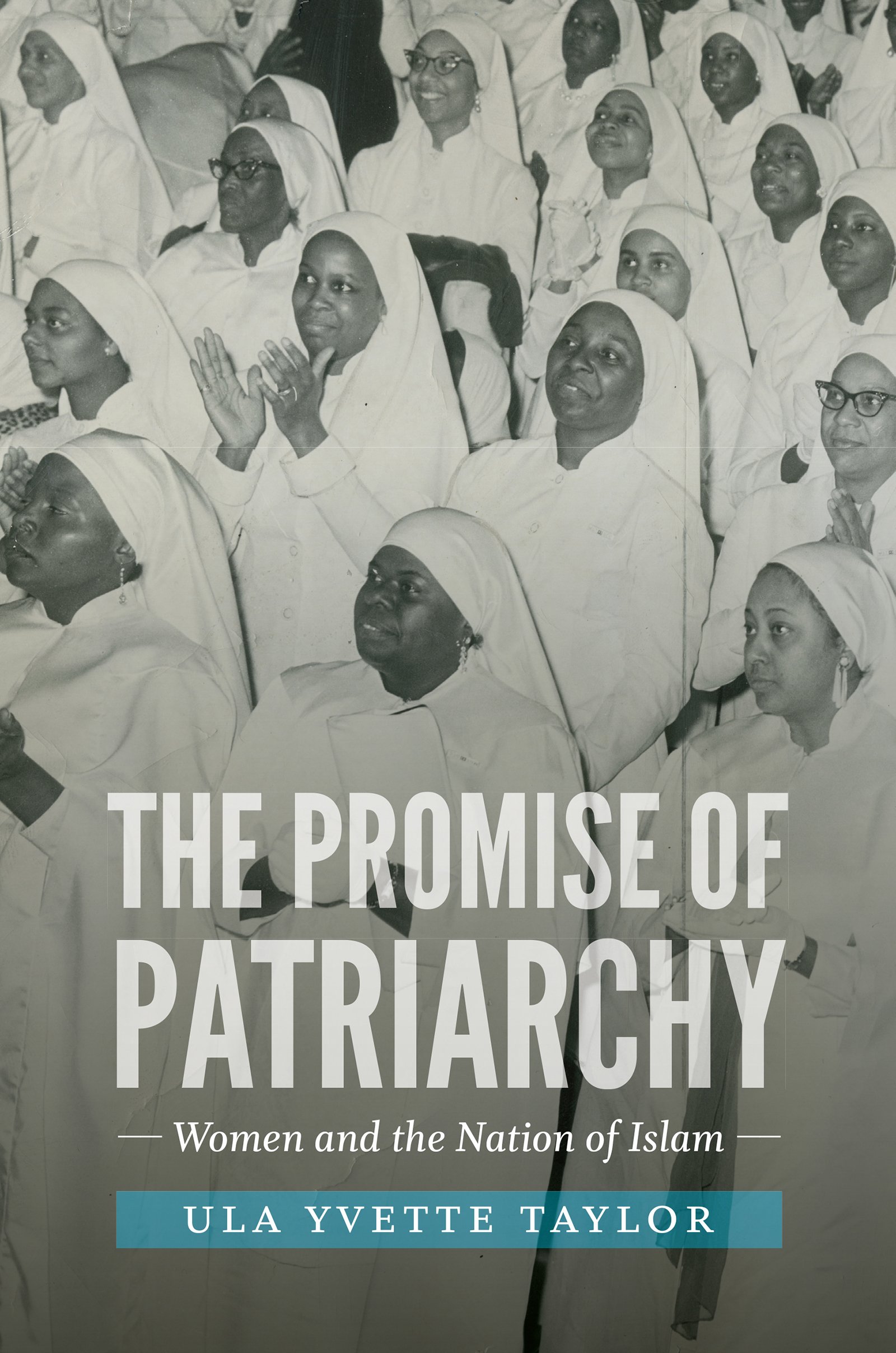

Controversy over the Nation of Islam (NOI) erupted in the news recently when Women’s March co-president Tamika Mallory was linked to NOI leader Louis Farrakhan. In the ensuing fracas, Mallory’s association with Farrakhan was placed in the context of the NOI’s historic place in the Black grassroots political landscape and lauded for its work in fighting white supremacy and redeeming Black manhood, most notably Malcolm X. What the NOI meant for Black women converts was notably absent in this contemporary debate and remains a missing page of the organization’s history. Ula Y. Taylor’s The Promise of Patriarchy: Women and the Nation of Islam steps into this lacuna by offering a richly detailed account centered on the experiences of Black women in this misunderstood organization and their contributions to its history.

Taylor uses the NOI as a “vehicle to understand how freedom and prosperity comingle around patriarchy” (5). This analysis provides important complexity to contemporary headlines that foreground slogans like “smash the patriarchy” and the increasing visibility of feminism while letting the many ways that patriarchy is structurally embedded in U.S. society and scaffolded around race, class, gender, and sexuality remain unexamined. Taylor reminds us that patriarchy was reinforced and embraced by both women and men. For the Black women who joined the NOI, patriarchy’s promise was appealing. It provided the potential of a mate and “securing husbands under obligation to provide, respect, and protect was intrinsic to their Nationhood choice” (5). These women’s motivation for marriage was linked to love, economic stability, and the need for protection in a Jim Crow nation which viewed them as hyper-sexual beings who were never chaste and never the victim of sexual assault. The reality was quite different and the vulnerabilities of Black women, their struggle to educate themselves and their children, and their desires for dignity and protection clearly shape the political choices we see them making when they join the NOI. As members of the NOI’s earlier iteration the Allah Temple of Islam (ATOI) women faced arrest, surveillance, and raids and kept the organization alive during waves of incarceration of leading men. The promise of patriarchy is inextricable from the perils of white supremacy.

Taylor’s book brilliantly pierces the mystique around the NOI’s norms and practices with close analysis of archival evidence. While the NOI’s food practices are often vaunted, she reminds us of the politics of austerity, noting that “Master Fard advocated eating sparingly at a time when in fact there was little opportunity to do otherwise.” (50) She historicizes the NOI’s “appropriating an Islamic world” (68) through dress during the challenges of World War II. She links the NOI’s cosmology to Cold War fears and Christian teachings. She dares to go beneath the blanket of anti-Semitism thrown over the NOI in response to its more virulent beliefs to tease out how some of the Black women in her book like Sister Thelma X encountered Jewish men and women in exploitative contexts and the understanding they drew from the experiences. In short, this book demonstrates over and over again that the lens of women’s history provides a more nuanced view of not just women but entire swathes of the Black political landscape.

Taylor does not elide questions of power. The problematic beliefs and behaviors of NOI patriarchs infuse the lives of the women who felt first hand “the tension between the oppressive and liberatory aspects of NOI membership” (75). From the implications of mandating large families on women’s bodily autonomy to prescriptions for women to remain charming, friendly, and upbeat to examples of male power trips such as W. D. Fard pressing Sister Burnsteen’s face into the papers she had painstakingly spent hours typing to demonstrate his preferred method of folding and tearing, it is clear that patriarchy came at a price. Women exacted the toll as well as paid it. Examples of women patrolling the boundaries of weight, modest and clean dress, and respectability abound in Taylor’s book.

The Promise of Patriarchy demonstrates that nation building through patriarchy, religious doctrine, and alternative lifestyle practices and institutions gained in appeal during the height of the Black freedom movement. In this period, NOI women pushed back successfully by working outside of the home, unevenly practicing conventions about modest dress, and engaging in active family planning even as its most visible men—Elijah Muhammad and Muhammad Ali–eschewed monogamy for extra-marital relationships that were demoralizing open secrets. In the decade after Malcolm X’s death, the NOI’s mix of nationalism, spirituality, self-help, and what Taylor defines as “the promise of prosperity” swept in a new membership from the ranks of civil rights organizations facing infiltration, harassment, cooptation, and decline. In the context of a vicious backlash against Black feminist activism in this period, the NOI provided an alternative rhetoric of “love, protection, and respect.” Despite this veneer, the undercurrent of women as emasculators still prevailed.

From beginning to end, Taylor’s book successfully demonstrates this constant dialectic between valorization and oppression that is part and parcel of patriarchy. NOI women chose the promise of family, health, economic stability, and male protection in an organization that remained “a socio-religious movement framed within masculinist Islamic traditions” (169). It is clear that for some Black women at some points in history this choice looked like freedom. While it may be easy to judge through the lens of history, Taylor’s book deftly reminds readers of the contemporary nature of these contradictions. Her final chapter is a tour de force of the historical context and religious history behind some of the hushed conversations about gender roles, motherhood, and household heads that are a staple of many religious and social spaces in the wider Black community that reflect the same dynamics seen in the NOI. To reframe this organization, considered to be on the fringes of Black political life, into a mirror where so many may see a glimpse of their hopes, dreams, and nightmares is one of the greatest contributions of this book.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.