Centering Women in the Nation of Islam

This post is part of our online roundtable on Ula Taylor’s The Promise of Patriarchy

In her 2008 seminal essay, “Women in the Documents: Thoughts on Uncovering, the Personal, Political, and Professional,” Ula Taylor reflected on her archival approach to her new project on Black women in the Nation of Islam (NOI). At the core of this study was the question of why anyone would “become a member of the Nation of Islam after the assassination of Malcolm X (El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) in 1965?” Like many scholars, Taylor looked to the NOI’s news organ, Muhammad Speaks, to shed light on this subject, but her approach to this archive differed. Recalling her research process she explained, “reading both hard copies and microfilm versions of the newspaper has allowed me to see it from literally two different angles. The microfilm enlargement process allows one to focus clearly on a specific article, but in doing so, one loses sight of the whole (the rest of the paper). For this reason, I prefer to sift through hard copies of the newspaper. Reading for the question of ‘why?’” Nearly ten years later, Taylor’s method has yielded the answer to this question and many others in her newest book, The Promise of Patriarchy: Women and the Nation of Islam.

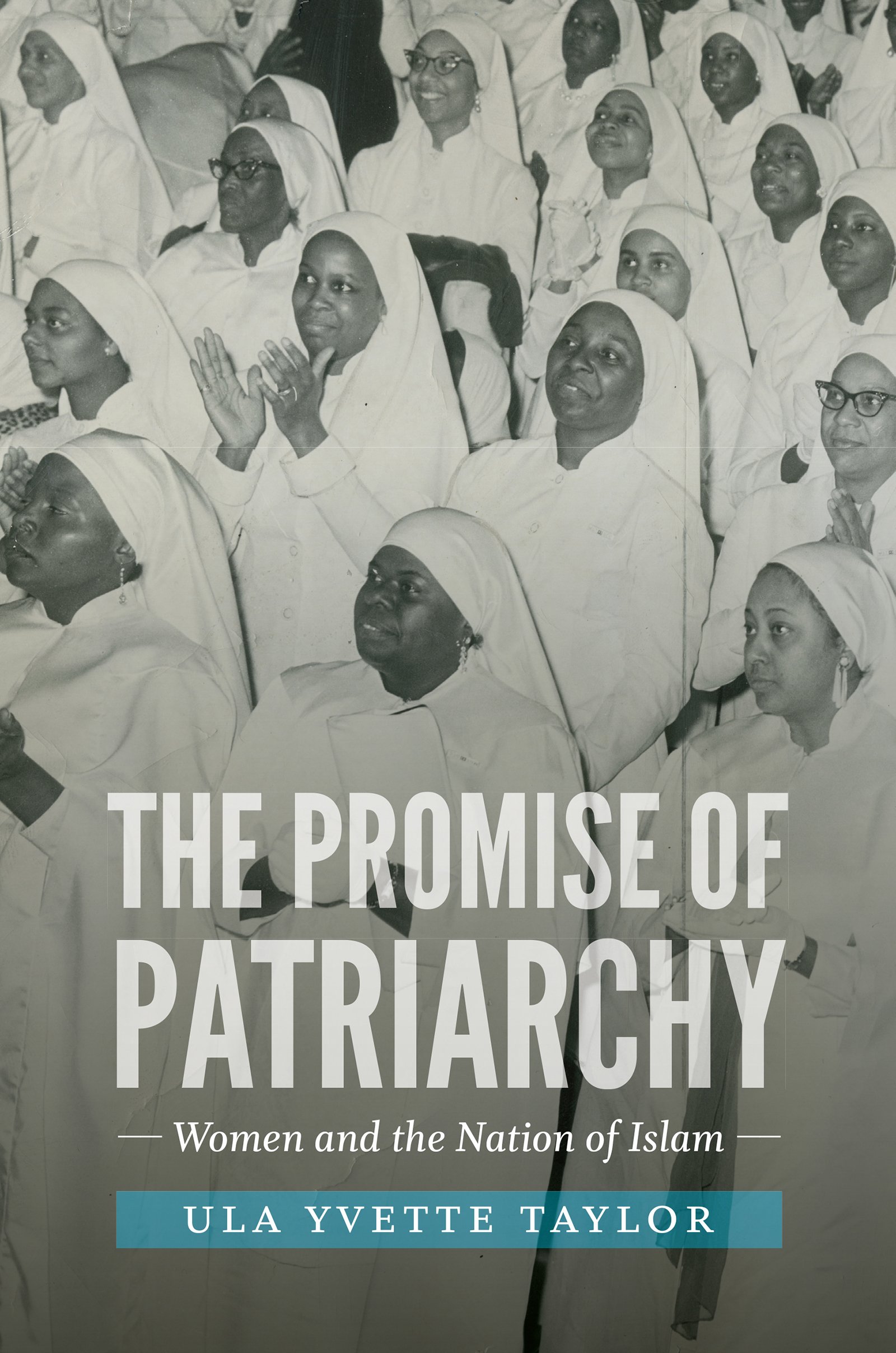

The first in-depth examination of women in the organization, The Promise of Patriarchy shows how and why Black women were drawn to the NOI. Taylor details how women navigated its complex web of gender, familial, and racial politics. In the process, she introduces readers to the lives and work of foundational members such as Clara Poole, Elijah (Poole) Muhammad’s wife, explores women’s roles in building the NOI forerunner, the Allah Temple of Islam (ATOI), charts the evolution of the Nation through World War II and the rise of its well-known minster Malcolm X, and its demise. Ultimately, The Promise of Patriarchy convincingly illustrates that Black women became life-long members of the NOI because it “offered them hope, stability, protection, and freedoms on their own terms” (184) even as it asked them to adopt a “puritanical feminine identity” (3).

This dynamic history is made possible by Taylor’s ability to see sources from a different angle. Her method is especially generative in the chapter entitled, “Allah Temple of Islam Families: The Dillon Report.” As Taylor explains, from 1931 to 1934, Poole and her husband helped build the foundations of the Nation of Islam through the ATOI in Detroit. Part school, part religious organization, the ATOI functioned as a conduit through which to spread founder W.D. Fard’s teachings and to cultivate a counter-public space in which the local Black community could assert their political, cultural, and social autonomy. The ATOI drew the attention of local white authorities and after several police raids members chose to hold meetings in their homes. They also removed their children from local public schools and began instructing them at home using ATOI curricula—a choice that drew the attention of the city’s Attendance Division and Public Welfare. Under the direction of Mariam S. Dillon, Detroit officials commissioned an investigation of the group, aiming to “re-enroll the children into public schools before ‘adopting a policy of aggressive action’” against ATOI parents (33).

Where others might see evidence of government repression, Taylor finds Black women’s autonomy. Using the Dillon Report, she gleans valuable information about ATOI women’s values and their ideas about the world around them. For example, Taylor finds details about the ATOI curriculum — which ranged from lessons that challenged white hegemonic history and culture to astrology and mathematics — to offer critical insight into the function and scope of the group. By reading for the question of “why” she uses these and other report specifics to show how the ATOI offered Black women and their children “a new way to think about themselves and the reasons for their oppression” as well as “new ways to take control of their own lives” (43). She also offers insight into why Black women were attracted to the organization and how they helped advance the ideological and organizational development of the collective that would eventually become the NOI.

Taylor also uses sources inventively to show how NOI women “trump[ed] patriarchy (122).” A key tension throughout the book is how Black women simultaneously adhered to the NOI’s conservative gender politics and found the group to be a positive and liberatory force in their lives. Many scholars have assumed that female members simply accepted Nation leaders’ ideas about womanhood and women’s roles. Taylor critically engages well-known sources to demonstrate how they challenged patriarchy, often while appearing to support it. Reading autobiographies, FBI records, and Muhammad Speaks articles anew, she shows how NOI women effectively functioned as breadwinners and decision makers within their families and liberated themselves from undesirable marriages, even though these activities went against the NOI’s prescribed roles for women. Taylor has long been an advocate of “critically engag[ing]…ideas” that “r[un] counter to [one’s] personal longings and convictions.” This approach proves productive in The Promise of Patriarchy, as she is able to shine light on the ways in which Black women balanced their fidelity to NOI principles while also asserting their autonomy.

Largely due to Taylor’s extensive research and archival method, The Promise of Patriarchy offers an important addition to the historiographies of African American women’s history, Black religion, Black Power, and Black organizing. It also engenders new lines of inquiry for future scholars, including how and where to locate more sources on female NOI members and the best way to ascertain Black women’s overall influence on the Nation and its evolution. Such an astute reading of sources also fosters new questions, most notably about the limits of existing archives in helping historians to understand NOI women’s successes in trumping patriarchy. Taylor’s attention to alternative readings of NOI sources provides a much-needed corrective not only to histories of this group but also to the study of Black women’s lives, spirituality, and organizing.

Taylor closed her 2008 article by asserting that historians should “think and theorize from [the] same documents” used in previous scholarship “not only to recover voices but also to disrupt those canonical discourses that have too often rendered African American women invisible.” Her newest book takes up this charge by offering new insight into how Black women transformed one of the most important religious and activist organizations of the twentieth century. The Promise of Patriarchy succeeds in answering Taylor’s question of why Black women would join the NOI and reveals it to be an organization through which thousands of women theorized and enacted liberation.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.