Removing the Confederate Flag, But Not Forgetting Its Legacy

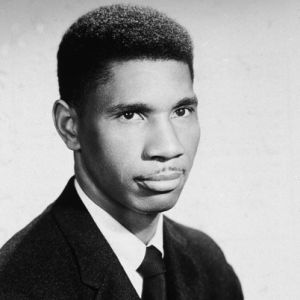

Today is the birthday of noted civil rights activists Medgar Evers and Thurgood Marshall. Perhaps, it is fitting to reflect on where we find ourselves as a country at this particular moment. In the aftermath of the Charleston shootings, people across the country are re-assessing the usage and the meaning of the Confederate flag. The Dean of the National Cathedral announced his intention to remove the stain glass windows honoring Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

Dean Hall’s decision came amid calls to remove the flag from the South Carolina state capitol, the removal of the confederate flag from the state license plates in Virginia, and numerous businesses ceasing the production and sale of the flag. These responses are an attempt to distinguish themselves from the Charleston shooter. For many people the incident in Charleston made them aware of the powerful and hate – driven meaning the Confederate flag has today.

The Confederate flag has historic value, but should be restricted to museum and public history venues not state capitols. I also applaud various businesses and religious organizations re-examining their promotion of the flag and whether or not it corresponds with their values. Yet, I am concerned about the trajectory of this path and its meaning to the American public memory. When the Charleston shootings are no longer front page news will the perception of the Confederate flag and America’s issues of race also change? In a few months or a year, as we continue in the spirit of Medgar Evers and Thurgood Marshall, will the response be we removed the Confederate flag, what more do you want? In other words, it is possible for people to think that by removing the Confederate flag sufficient work has been done regarding American race relations.

One of the defining factors of a society is the symbols and memorials that promoted and preserved. The removal of the Confederate flag cannot remove the deeply entrenched legacy it would symbolize. The original intent of the flag was to represent the Army of Northern Virginia and later the Confederate States of America whose secession from the Union was based on the infringement of the government on the states’ rights regarding slave ownership.[1] During the war, the flag would become a symbol of opposition on and off the battlefield. The South was a war zone and during and after the war the flag was would come to symbolize an obstinate level of resistance against the Union. For example, Vicksburg Mississippi fell to Union forces on July 4, 1863. Independence Day was not celebrated in the city until the end of World War II. In the midst of Reconstruction and Redemption, the flag would bring together Confederate veterans and supporters as they engaged in extralegal acts of terror for the purposes of establishing order in the South. The reality of these activities was the assault, lynching, and general terrorism of black Southerners. The flag was present at political rallies, political offices, and in homes a segregation was implemented throughout the South.

When African Americans would challenge segregation codes throughout the South, the flag was in the police cars, police departments, and at demonstrations as a symbol of loyalty to the preservation of the “old ways.” In the 150 years since the end of the Civil War, the flag has been incorporated into various statutes and memorials. It is deeply tied to the racism and a resistance to any pursuit for equality and liberty by African Americans.

The act of removing the Confederate flag from various venues and merchandise does not lessen the legacy of racism in the country, and all of the ideologies it would embody. Something must arise in its place. There must be a concerted effort to engage with the country’s history and racial legacy while also progressing forward with substantive change. The substantive change advocated by people like Medgar Evers and Thurgood Marshall.

[1] For Confederate States of America Papers see Yale University’s Avalon Project: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/csapage.asp

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.