Gender, Civil Rights, and the Case of Odell Waller

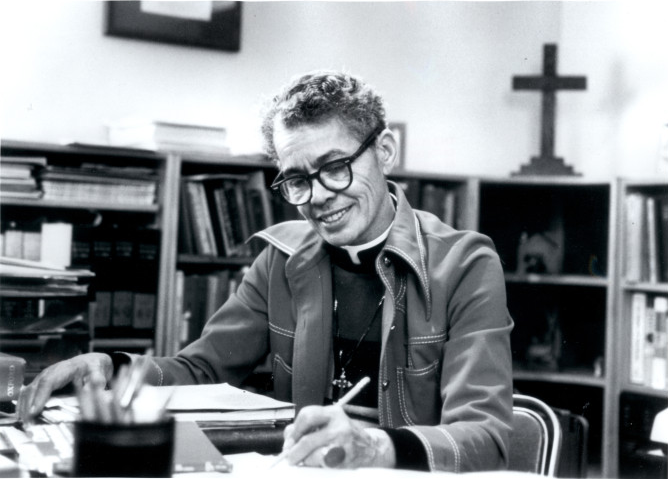

Pauli Murray is a central figure of women’s activism. Her career spanned five decades and included work in the labor movement in the 1930s, the civil rights movement and related legal scholarship in the 1940s and 1950s, teaching, feminist scholarship and activism in the 1960s and 1970s, and ordination to the Episcopal priesthood in 1977.1 Her early years as a civil rights leader (1935-1945) and her search for an inclusive American society shaped her identity as an activist and scholar. As field secretary for the Workers Defense League (WDL) during the 1930s, the official defense agency for the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU), Murray gave voice to the working poor and politicized their experiences within discourses of social justice and civil equality. The WDL defense of twenty-three-year-old sharecropper Odell Waller, who was sentenced to death for fatally shooting his white landlord, led Murray on a tour to raise funds for Waller’s defense. Waller’s execution in 1942 after an unsuccessful appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court intensified her pursuit of social justice and gender justice issues.

The Odell Waller case occurred in the Great Depression and World War II eras. This case raises fundamental questions concerning not only economic and racial justice, but also the role of African American women in redressing the socio-economic conditions that oppressed women and families. What recourse did Black sharecroppers have to secure wages and crops owed to them by landlords? What role did race play in predetermining the outcome of the Waller case? At a time when lynching, economic exploitation, and social violence were endemic throughout the South, Odell Waller used his own agency to demand economic justice for himself and his family, creating in that process an expansive community of people seeking and demanding freedom from economic and racial repression.

Odell Waller moved onto land owned by Oscar Davis near Gretna, Virginia, on January 2, 1939. The property consisted of tobacco, corn, and wheat farms. The agreement that Waller entered into stated that Davis would furnish the supplies and tools and Waller, supplying the labor, would receive one-fourth of the product. Despite this agreement, Waller was compelled to pay for fertilizer.2

In addition to owing Odell Waller, Davis also owed Waller’s aged aunt and adoptive mother, Annie Waller, four weeks’ pay for nursing Davis’s ailing wife.3 Annie never received the $7.50 payment. After some dispute, Waller had to abandon any immediate claim to the money due him for the tobacco along with the money he had spent for fertilizer. Waller then traveled to Baltimore, Maryland, to find work. While Waller was in Maryland, Davis evicted Waller’s wife Mollie and his mother, both of whom had worked on the Davis land.

When Waller returned from Maryland he secured a truck to receive his share of the wheat, which had been worked on by his wife, his mother, and himself. He went armed because he had previous experience with Davis and knew Davis’s general temperament as a “bad man” in the neighborhood. Davis also had previously threatened Waller with bodily harm if he tried to press his claim. When Waller arrived Davis told him he wasn’t “going to let him have a damned thing” and stuck his hand in his front pocket where he usually carried a pistol. In fear for his life, Waller grabbed his own pistol and fired several times at Davis, who died some days later. Fearing mob violence, Waller fled and was captured in Columbus, Ohio, where he was extradited on August 6, 1939, to Virginia. Despite threats of mob violence and lynching, the presiding judge refused to grant a change of venue for the trial.

The Odell Waller case reveals that African American women, who often lingered in the periphery in American society, moved to the center as activists and social reformers. Annie Waller, Odell’s aunt and adoptive mother, who worked as a domestic servant and field hand from early childhood to old age, visited churches and labor unions in New York for several weeks in December of 1940 to raise awareness of her son’s plight and funds for his legal expenses. Expressing that Waller was “always a good boy who wanted to take care of his mother and wife,” at an organizational meeting of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Annie Waller demonstrated her capacity to be an activist and social reformer. Her activism gave voice to the recovery and articulation of the experiences of African American families and women in the Jim Crow and Jane Crow South.

Annie Waller and Pauli Murray went on a speaking tour of several cities in 1940 including New York City, Washington, D. C., Minneapolis, Chicago, Detroit, and Boston. In each of these cities, Waller and Murray established Waller Defense Committees, which the WDL and the NAACP supported financially. These defense committees sought to broaden public knowledge of the issues facing Odell Waller and sharecroppers in the South. Black women comprised a significant number of Waller Defense Committee members. The funds raised by Annie Waller and Pauli Murray provided the resources for Waller’s stay of execution, which the Virginia Supreme Court granted with a writ of error.4.

Annie Waller and Pauli Murray’s tour continued in 1941. Both women gave speeches at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, pastored by Rev. Adam Clayton Powell. Transcending the sexual politics of patriarchy in the Black church, Annie Waller told a simple, straightforward story of the events leading to the tragedy of her son’s arrest without embellishment or exaggeration.5. As an activist she analyzed, advocated, and agitated for social justice for her son.

In 1941, Murray co-authored a booklet with Murray Kempton, All for Mr. Davis: The Story of Sharecropper Odell Waller. Of particular significance is Murray’s discourse on Annie Waller. According to Murray, Annie Waller was a petite woman whose frame was “humped with a stoop” caused by working long days in the tobacco fields. Her hands were purple and bald with crop blight “from years of handling cow teats and dry tobacco leaves.” She did not know her age and she depended upon children to read letters. However, “she could work hard” and “she knew her rights.”

Despite appeals for a stay of execution to Virginia Governor James H. Price, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and a request for review by the U.S. Supreme Court, Odell Waller was electrocuted to death on July 2, 1942. In her poem “Prophecy,” Murray provides a retrospective on Waller stating, “I sing of a new American, Separate from all others; I am the child of kings and serfs, freeman and slaves, I have been enslaved, yet my spirit is unbound; I have been cast aside, but I sparkle in the darkness; I have been slain, but live on in the rivers of history.”

- Jean Humez, “Pauli Murray’s Histories of Loyalty and Revolt,” Black American Literature Forum, Summer 1990 ↩

- “All For Mr. Davis: The Story of Sharecropper Odell Waller,” Box 72, Folder 1250; Pauli Murray Collection, MC 412, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, Schlesinger Library for Women, Cambridge, MA. All subsequent details about Odell Waller, unless otherwise noted, comes from this collection. ↩

- Annie Waller’s sister, Dolly Jones, was Odell’s birth mother. Odell was raised by Annie and her husband Willis Waller. ↩

- Virginia Court Grants Waller Writ of Error,” Worker’s Defense Bulletin, March 1941, Box 72, Folder 1249; MC 412 ↩

- WDL Bulletin, MC 412, January 1941, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, Schlesinger Library for Women, Cambridge, MA ↩

This is just what we needed for our HS racial literacy class! Thank you. We are exploring specific periods of racial domination and progress in the U.S. context and students have limited understanding about the intersections that cross in these discourses. Adopting all kinds of fallacies advanced in textbooks, we can now point them to primary source research like this. Thank you for extending research done by others by including information from the Schomburg. We are heading there this week. #CiteBlackWomen

Thank you for writing this. Another African-American woman who played an important role in the Waller defense was Layle Lane, a teacher union leader and close ally of A. Philip Randolph (she assisted him in the organizing of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and was key to the First March on Washington he organized during WWII). Lane was also on the board of the WDL. This case was important for African-American activists in the Socialist Party milieu.