The Families of the Louisiana Native Guards

This post is part of our online forum on Black Military Families in the Nineteenth Century.

On May 1, 1861, the mayor of New Orleans, John T. Monroe, recognized Black Creole women for their wartime bravery and fidelity. This was a day before the 1st Louisiana Native Guards organized with Black Creole men of the city. Black women led the way for service, and after the Union Army arrived (in 1862), Black women were once again first in aiding the Union military by working as nurses and laundresses, months before their men could join.

Once the Native Guards were in the Union Army, Black Creoles worked together to change the society of Louisiana for the betterment of all Black people. Black men who joined fought to protect their wives and children from rebels, and in some cases, Union soldiers, and in return, Black women labored and protected their men and children while supporting the economy. While similar situations occurred in the North, with Susie King Taylor being one of the most famous, New Orleans was a special location because of how early they joined the military (in comparison to northern Black men), and the free Black Creoles who had the money and education to uplift their community. Without the families of the Native Guards, the Black regiments would have been hollow as the men were fighting for more than just ending slavery, many were fighting for a better world for their families.

The Afro-Creoles of New Orleans realized soon after Louisiana’s secession that if they did not toe the line, they risked the relegation of their political and civil rights which they enjoyed for generations. Free Blacks owned land, operated businesses, and some were quite wealthy, as the scholarship of Matthew Wills notes. The years leading up to 1861 already showed them the state legislature wanted to remove their group for being a threat to the institution of slavery because the legislature already passed laws limiting the number, freedom of movement, and legal rights of free Blacks.

Months before the Civil War began, there were debates over colonization—forced deportation of Black people from the U.S. to Liberia, or some other nation—and the Louisiana legislature already passed a law to begin enslaving free Blacks if they did not leave the state. Before the law was active, however, the populace was engrossed with secession politics, and for a time the state legislature let up on removing all free People of Color. This was a small window, but one the Black populace exploited to maintain their place in society.

In March 1861, Jordan Noble, the last surviving Black drummer boy from the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, organized Black Creoles in a series of meetings to consider joining the home guards so they could show commitment to the new nation they were trapped within. Demonstrating loyalty was key for all as Vigilance Committees and other groups were within New Orleans that punished any who were a threat to the fomenting Confederacy. While similar organizations existed throughout the nation, the New Orleans’ groups were particularly organized before the war. Even white people were targets if they displayed Unionist sentiments, with some being run out of state or lynched. Thus, Noble and those who followed him knew they had to capitulate if they wanted to avoid fates that included enslavement, rape, lynching, and death. By April, they had enough signatures to present a plan to form a home guard unit manned and officered by Black Creoles who would patrol the streets of New Orleans as their ancestors had done earlier in the century.

Black women also met to find ways of displaying their fidelity to Louisiana, and their men who could soon join the home guards. They met alongside the men, and in April, they too were ready to present a proposal to the mayor. Monroe publicly recognized their petition, and the following day Governor Thomas Moore did the same for the men. Black women further demonstrated their support through weaving silk flags and sewing uniforms, which was an act northern Black women (in the Union) routinely performed, as historian Holly A. Pinheiro, Jr., details; and their actions within Louisiana were critical because Moore had no intention of using the Native Guards and most of the men were not issued uniforms or equipment. The charade worked quite well, proving to the legislature that the Black populace deserved to remain in the state. The publicity resulted in children of men in the Native Guards doing projects on their fathers, and young Black kids marveled at the sight of Black men marching in the streets. Their display became too effective, and the state legislature disbanded the Native Guards, early in 1862, for fear they proved Black men were equal to whites. However, they were soon brought back by the governor when it was evident the Union Army was going to liberate New Orleans. Nevertheless, the Confederate military put up little defense once the Union Navy harbored on its shores, and on May 1, 1862, Major General Benjamin Butler took control of the city.

The presence of the Union Army gave Black women a new opportunity to either prove their loyalty to the Union or stay out of the equation altogether. White women, in contrast, were already seen as wholly disloyal, to the degree that Butler famously issued General Order No. 28 to force them to respect Union soldiers. Black women, however, proved their loyalty to the Union and their families. While their men could not join until August 22, Black women were in Union camps immediately, working in numerous crucial roles. Their presence in Union lines was a boon to the military, and they helped to prove that the Black populace was indeed loyal. However, their presence in Union lines exposed some to lascivious behavior from white men who thought of all Black women as little more than enslaved people who they could mistreat as other white men had done for generations, as historian Tera W. Hunter highlights.

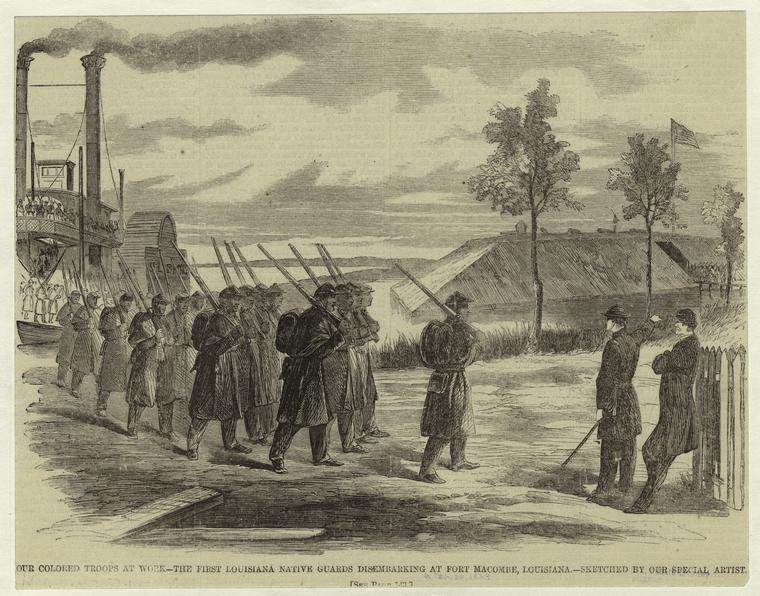

By the fall, the Native Guards were constituted in the Union Army by General Butler, and Black men marched through the city proudly declaring their loyalty to the Union. The 1st Regiment was quickly followed by two more with an artillery and engineer unit operating as well. The following year, more Black regiments were formed, and the new commanding Major General, Nathaniel Banks, redesignated the regiments to the Corps d’Afrique.

Black women continued to serve the Union military, and the presence of their men in the military helped to offer a new layer of protection. When white enslavers attempted to rape or beat Black women, their men could physically protect them or ask their superiors to have the man arrested. For instance, Colonel Spencer Stafford commanded the 1st Regiment, and he petitioned both Butler and Banks to offer more protections for the family members of those who served.

Eventually, the Union Army forbade white owners from evicting the family of any man in the regiments, and those who hurt them were often imprisoned by the military. However, there was one group who still found ways of hurting the wives, girlfriends, and sisters of those who served: white Union officers. In the camp of the 4th Corps d’Afrique, a group of officers assaulted numerous Black washerwomen in a single night, and a few of the Black soldiers (in retaliation to the assaults) attacked the officers when they found out. Their anger at similar unpunished incidents was a partial impetus for the mutiny at Fort Jackson which occurred in December 1863. White men from the North were reinforcing and reliving the same crimes as generations of southern white men before them, but the Black men and women part of the Corps d’Afrique used the agency military service gave them to fight back. Once federal authorities realized Black men would kill a white officer if they found one raping their women, the military worked to separate the two even further.

The children of the Native Guards benefited from the actions of their parents. The Union Army built schools specifically for the regiments, and the new schools educated Black kids and women as well. Additionally, the federal government opened new schools and opened more as the state moved further into Reconstruction, allowing for hundreds of Black children to receive an education. Thus, military service opened the door for future generations of Black people. Their heroes, through all of this, were the men who marched the streets and killed white men in the Confederacy. Thus, their children lived for many years protected by the knowledge their fathers and mothers were serving the military to further the place of all People of Color in the nation.

We see a reciprocal relationship between the families of the Native Guards and the men who served. The families supported the men, and their support helped to bolster claims of loyalty by the African American populace of Louisiana. At the same time, the men serving in the Native Guards protected the women and children when they could. Their actions made them heroes to their children, and as one captain hoped, helped to set the stage for a better life for all People of Color after the Civil War.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.