Tuskegee’s Civilizing Mission

From his academic career at the Hampton Institute (1872-1875) in Virginia until his death in 1915, Booker T. Washington preached that technical education was more than a tool to build character—it was a solution to uplift Black peoples around the globe. He laid down his message in a speech delivered at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895 in which he told the African Americans in attendance–while also speaking more broadly to Black people everywhere–to “Cast down your buckets . . . in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service, and in the professions.” This essay looks at how Tuskegee educators and supporters promoted Booker T. Washington’s Hampton-Tuskegee model of education in Africa during the age of American and European imperialism from the Berlin Conference of 1884 until the opening of the Booker Washington Institute in Kakata, Liberia, in 1929. The push for a Tuskegee Institute in Liberia indicated a coordinated diasporic effort to mobilize resources and institutionalize Black uplift. In the current age of Black Lives Matter, understanding the diasporic history of Black peoples is important to understanding how African Americans and Africans connect with each other in an era of continued discrimination and exploitation.

Booker T. Washington has become one of the most controversial and misunderstood figures in Black history. For instance, W.E.B. Du Bois critically called Washington’s Atlanta speech the “Atlanta Compromise.” Washington’s critics, including Du Bois, labeled him an accommodationist because of his apparent acquiescence to white society and imperial powers, who viewed Washington’s speech as justification for the subordination of colonial peoples. But looking deeper, Washington envisioned the Hampton-Tuskegee method as a solution to elevating the status of African peoples and building diasporic connections through education and struggle. The attitudes of Tuskegee students who went on missions to Africa and the outreach undertaken by Washington’s supporters contributed to how these diasporic connections were made. As historian Frank Guridy has argued, “Tuskegee became a site of diasporization not only through Washington’s efforts, but more importantly through the agency of people of African descent who were inspired by his message of uplift.

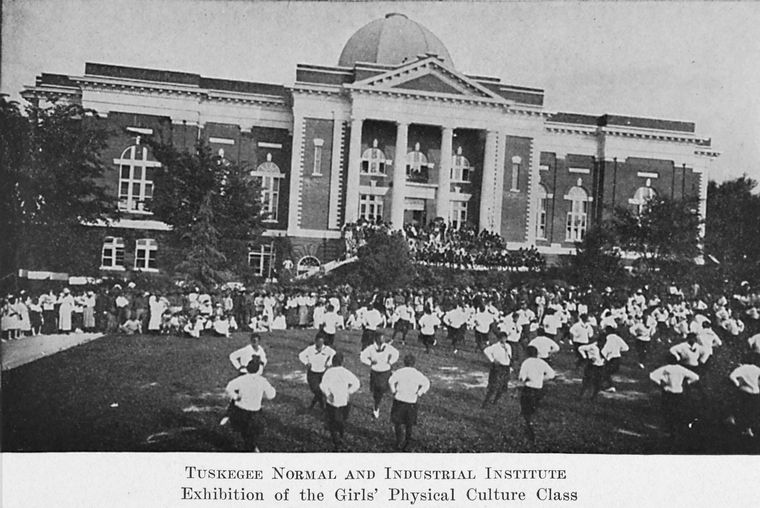

Booker T. Washington founded and served as the first principal of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in 1881, fifteen years before the Plessy v. Ferguson case upheld the “separate but equal” clause, and at a time when Black intellectuals like Washington, Du Bois, and Ida B. Wells were fighting for Black progress and civil rights. While Washington acknowledged that white America had positioned Reconstruction to fail from the beginning, he also criticized Black Americans for being culpable in its failure, arguing that African Americans had reached not only beyond their capabilities, but expected too much from white America to accept them. Washington advocated a gradual approach to civil rights that encouraged African Americans to accept their status for the time being and forgo fighting for higher education, political power, and civil rights. Washington believed that African Americans should concentrate on skills they already had and focus on tangible goals. Their energies should be focused on industrial education and achieving economic independence. He believed that in the long term, African Americans would eventually gain full participation in society by showing themselves to be responsible, reliable American citizens. While Washington’s ideas angered many of his contemporaries, his ideas provided a practical solution to African Americans and Black colonial peoples who sought to lift themselves up from their social positions. It is important to understand that Washington was not merely an accommodationist surrendering to white society. He understood the social, racial, political, and economic climates and worked with what was available. However, Washington’s ideas about race appealed to Northern white philanthropists and gained the attention of pro-imperialist supporters in the United States and Europe.

When Europe carved up Africa in 1884 at the Berlin Conference, they looked for the most effective solution to manage their colonial subjects in their new colonial possessions. Washington’s “Atlanta Compromise” speech had piqued the interest of Baron Beno von Herman auf Wain who was a member of the German Colonial Economic Committee (Kolonial Wirtschaftliches Komitee [KWK]). Looking to establish their own cotton empire in the German colony of Togo to end their reliance on American cotton imports, German colonial officials reached out to Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee, the premier technical school of the time. The KWK looked to educate the Togolese in large-scale cotton growing and to make them more manageable subjects. Believing that African American guidance was essential for Africans to organize and uplift themselves, Washington sent a group of Tuskegee teachers to Togo to train the Togolese using the Hampton-Tuskegee model. Washington believed that the Hampton-Tuskegee model provided more than industrial education, it also shaped the character of Black peoples and offered them a path to improvement.

While the Togo expedition was short-lived, it gained the attention of other European colonial officials and African intellectuals in places like Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (modern-day Sudan and South Sudan), Belgian Congo, and most successfully in South Africa. Early in the twentieth century, Western-educated South Africans who visited Tuskegee quickly learned the tenets of industrial education and accommodationist politics espoused by Washington. John Langalibalele Dube, a Christianized Black African, was inspired by Washington’s Up from Slavery a widely read work among educated Black peoples in the American and European colonies. Inspired by Washington’s message, Dube implemented Washington’s Hampton-Tuskegee model in Natal, South Africa, marking the beginning of Black industrial education in the region and sparking political demands for self-determination. Dube influenced movements to spread the Hampton-Tuskegee model in response to the loss of Black civil rights, prompting African leaders to seek ways of joining the emergent capitalist society. Though never visiting Africa himself, Washington welcomed several African leaders to Tuskegee. Davidson D. T. Jabavu, Black politician and “the father figure of African education,” was profoundly influenced by Tuskegee. After he graduated from the University of London, the South African Minister of Native Affairs commissioned him to make an active study of the methods being used at Tuskegee, with a view of adopting them in connection with the education of native South Africans. Within several years, Jabavu helped to establish the South African Native College at Fort Hare, based in part on Tuskegee’s curriculum. The leadership elite followed many of the successful doctrines of accommodation that Booker T. Washington supported. Dube’s goals were not only to establish a Tuskegee in Africa but to ultimately obtain civil rights in a racist society.

Liberia was of economic interest to the US and Europe, and it was of unique interest to Tuskegee as well. Liberia was an independent African state that was made up of African American returnees and Africans. Washington and the Liberian Commission, founded in 1909, worked to make Liberia the hallmark of the international Hampton-Tuskegee model, a beacon of intraracial relations between two diasporic peoples. In practice, African American returnees tended to look at native Liberians as inferior similar to how white European colonizers viewed native populations. Regardless, several Liberians were already interested in establishing an industrial school like Tuskegee. Liberian students wrote letters to Booker T. Washington, expressing their desire to attend Tuskegee. In 1911, interest in Liberia came from the Phelps-Stokes Fund, a nonprofit foundation created to improve education among African Americans and Black Africans. Their combined efforts helped establish the Booker Washington Agricultural and Industrial Institute in 1929, the first industrial school established in Liberia. The school used the Hampton-Tuskegee model to teach the dignity of labor in trades and agriculture and to build transnational connections. For Tuskegee, this was an important step in showcasing not just the agency of African Americans, but also the desire of Africans to improve their own lives.

The Hampton-Tuskegee model’s purpose was to build connections between two peoples who shared a common struggle of exploitation and subjugation to bring about racial uplift using skills they already were familiar with. Booker T. Washington supported a gradualist approach to civil rights because he was perceptive to the political and racial landscape of the time and knew that the accumulation of capital and showing whites that Black people shared the same goals as them was an important step to dismantling the barriers of discrimination. The use of this educational model by its supporters highlights a complex relationship between two diasporic peoples in an era of global expansion and racial discrimination. The Hampton-Tuskegee model was a tool for racial progress, and presently, as then, understanding ways to navigate through the barriers to racial progress are paramount to the betterment of all Black peoples.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Wow! Thank you so much for writing this. It is so alarming to me now, as even today, a lot of what Mr Washington was advocating back then is needed even more today. We need to realize that there are different forms of slavery and one of the worst forms of it is (Economic). Too many of us don’t want to do anything to prepare ourselves to climb up the economic ladders of success. Our Fore Parents and ancestors are tossing and turning in their graves, because of the squandered opportunities our current generation is not utilizing or taking advantage of.