Black German Women and the Fifth Cross-Cultural Black Women’s Studies Summer Institute

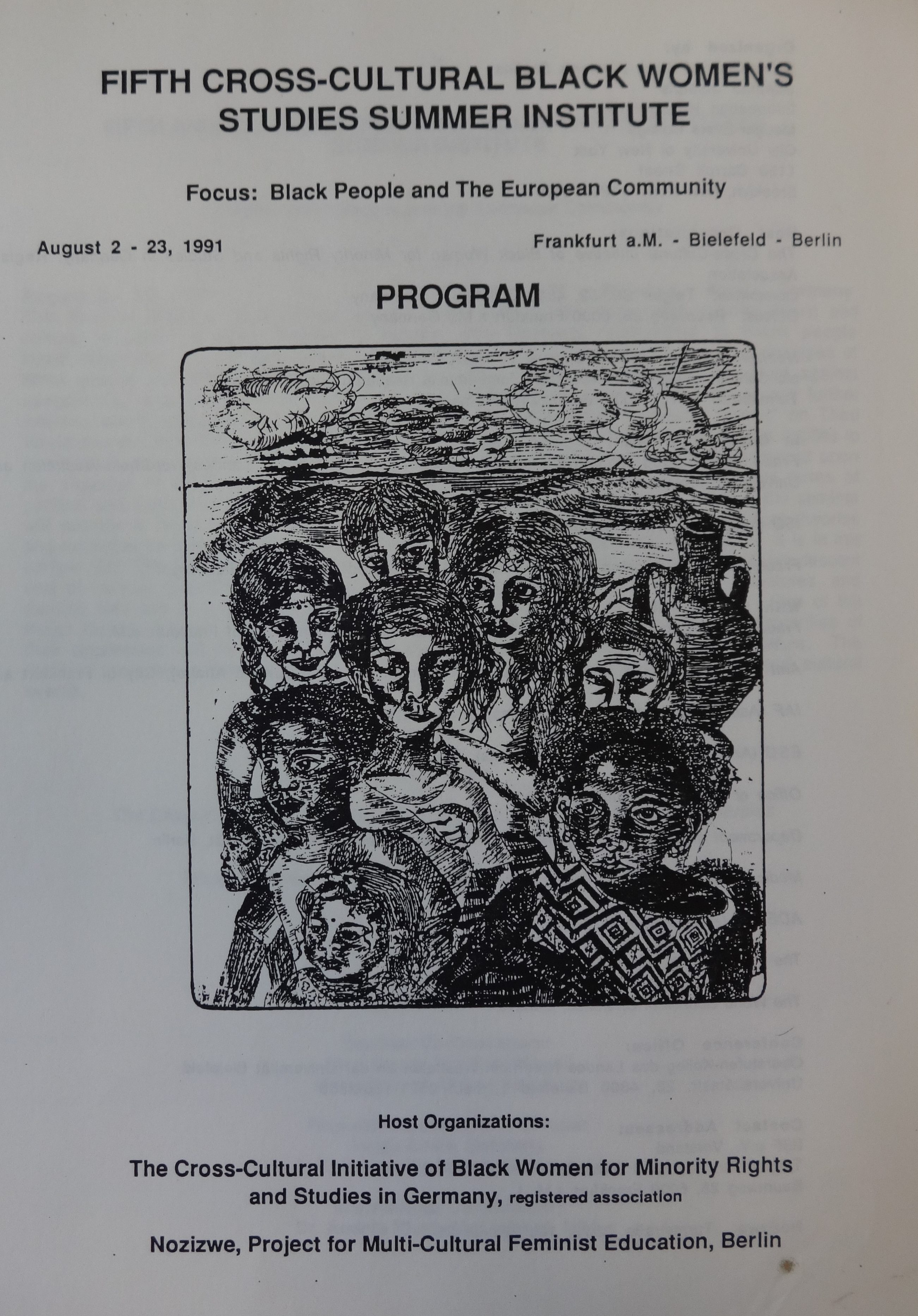

When the opening session of the Fifth Cross-Cultural Black Women’s Studies Summer Institute began on August 2, 1991, in a reunified Germany, hundreds of women of color—including Beryl Gilroy, Philomena Essed, and Melba Wilson—assembled in Frankfurt am Main. This three-week summer institute, which also took place in Bielefeld and Berlin, was a significant moment for Afro-German women. It was the first time that an entire international conference in Germany had been dedicated to the topic of “Black People in the European Community” (Schwarze Menschen und die Europäische Gemeinschaft). Influenced by the United Nations World Conferences on Women, the Cross-Cultural Institute emerged in 1987 with headquarters in New York and London, and centered the intersectional experiences of women of color worldwide. The 1991 Institute was no exception, especially as it continued to serve as a space for international understanding, community building, and kinship for a diverse group of activists, writers, workers, academics, and theorists.

Black German women’s organization of and participation in the 1991 Institute represented Black women’s internationalism and what scholar Tracy Fisher labels transnational Black feminism—a “feminism that shifts the geographical lens away from the limits of a hegemonic US racial landscape.” Sharing a feminist engagement, Black German women used this institute to underscore the necessity to combat multiple forms of oppression, to reject the claim that Europe, and by extension European identity (Europeanness), was solely white, and to show how Fortress Europe’s discriminatory policies and discourses negatively impacted minorities of color in Europe. This emphasis demonstrated how Black German women’s praxis of Black women’s internationalism foregrounded an intersectional approach; involved the interplay of the global, national, and local; and entailed forging affective connections to Black women and women of color in Germany and elsewhere. As a result, Black German women constructed a transnational network that extended encouragement, offered support, and promoted feminist solidarity.

Afro-German women not only relied on institutional support from local Black German organizations such as Afro-German Women [Afro-deutsche Frauen] (ADEFRA) and Initiative of Black Germans [Initiative Schwarze Deutsche] (ISD), but they also collaborated with other institutions and groups, including the French and German chapters of SOS Racism, the Department of Multicultural Affairs in Frankfurt am Main, the Protestant Church, and Nozizwe: Project for Multicultural Feminist Education, a Berlin-based migrant women’s organization. Black German women such as Marion Kraft, Katharina Oguntoye, Helga Emde, May Ayim, Jasmin Eding, Shelia Mysorekar, Judy Gummich, Modupe Laja, Ria Cheatom, and others coordinated activities and excursions or presented on panels; many of these women were members of ISD and, its feminist sister organization, ADEFRA. The collaboration, conversations, and connections that transpired at the institute certainly informed Black German women’s perspectives and political consciousness within their larger movement—a movement that pushed for unity, equality, and social change in Germany.

Given Black Germans’ social realities in a nation that experienced a resurgence of nationalist rhetoric and racial violence against refugees, migrants, and non-white native Germans, the 1991 Institute helped these women expose the fact that the government failed to adequately address instances of racial discrimination and that racism had not abated in the post-Holocaust German landscape. This was a point that Dr. Andrée Nicola McLaughlin, the founding international coordinator of the institute and a professor from Medgar Evers College wrote in a 1992 letter to members,

“even though German society is in the throes of profound structural change and experiencing an upsurge in racist violence, our German sisters—members of a relatively young Black national community— courageously undertook initiatives to conduct the 1991 Institute and to mount a tremendous fund-raising effort.”

She continued, “their endeavors made possible increased national and cultural diversity of delegates in attendance and simultaneous translation at Institute events.” 1 In this way, Black German women used events like this to publicize their racialized experiences within and beyond Germany.

The 1991 Institute also reinforced the idea that Black German feminism and Black Germanness were important on a global scale and helped Black Germans garner more recognition nationally and internationally. After the Third Reich, post-World War II West Germans avoided public discussions of racial difference and racialization, and anti-Black racism was often normalized in everyday symbols and practices. Yet some Germans did harbor neo-racist beliefs with regards to migrants, in which they were deemed culturally incompatible in German society. Within mainstream West German women’s and lesbian movements, there was hardly an engagement with intersectional approaches. Therefore through the event, Black German women affirmed their personal and collective experiences in a society that continued to mark them as un-German or foreign. They also were unabashed about stressing the critical concerns of women of color across the globe. In many ways, this Cross-Cultural Institute renewed their political work, in which these women vocalized developments that were frequently silenced at home, broadcasted their herstories, and spread knowledge about their Blackness and Germanness, reimagining notions of Blackness and Europeanness in the process.

At the institute, Black German women along with other attendees were emboldened by their experiences and embodied their intersectional feminist politics through the production of the “1991 Resolutions.” The resolutions (nine in total) sought to address the violent legacies of colonialism and imperialism as well as the extermination of indigenous communities and cultures. In an effort to resist global white supremacy, institute attendees also described the forms of institutionalized racism, sexism, and xenophobia that existed. They also acknowledged and discussed how participants in the institute were ensnared in structural webs of inequality and exclusion. These resolutions made an impact, especially as they validated the participants’ experiences, produced knowledge in and beyond Europe, and showed solidarity and coalition building in action.

Dealing with aspects of feminism, community, and politics, the resolutions served as intellectual interventions against the legacy of European empire, the racism of South African apartheid, and the restrictiveness of Fortress Europe. The resolutions helped participants productively channel their common outrage and dissatisfaction, and signified how these women refused to remain silent about their marginalization. From New Zealand to Ghana, these women used the institute to bear witness, while also stressing the significance of their lives as women of color and their efforts at resistance and activism. Together these transnational Black feminists showed that their praxis of cross-cultural encounters “offered an example of the political power of women for the future.”2

- Andrée Nicola McLaughlin, “International, Cross-Cultural Black Women’s Studies Summer Institute: Letter and 1991 Resolutions,” January 16, 1992, Box 52, p. 1, Audre Lorde Papers. ↩

- “‘Schwarze Frauen stehen in Europa ganz am Rande’: Interkulturelles Sommer-Seminar für Frauenstudien,” Frankfurter Rundschau, August 5, 1991, no. 179, Cheatom Collection, np. ↩