Interracial Intimacy and Film as Social Commentary

Fifty years ago, the Supreme Court struck down anti-miscegenation laws in Loving v. Virginia. In 1969, the first interracial sex scene occurred on screen in Tom Gries’ 100 Rifles. While interracial kisses had occurred on screen before 1969–Islands in the Sun (1957), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1967), and the Star Trek episode “Plato’s Stepchildren” (1968)–the 1969 Western 100 Rifles contains the first interracial sex scene. Forty years later, in 2009 Keith Bardwell, a judge in Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana, refused to marry an interracial couple because, as he expressed it, he worried about the children of the relationship.

As Bardwell’s refusal to marry an interracial couple in 2009 shows, even with the Supreme Court’s decision in Loving, lingering fears remain about interracial relationships, and those fears are couched within arguments of domesticity and procreation. Nella Larsen, in her 1929 novel Passing, references the “Rhinelander Affair,” an actual divorce trial where wealthy, white New Yorker Leonard “Kip” Rhinelander sought to divorce his wife Alice when rumors started to swirl about her father’s “mixed” ancestry. Reviewing Larsen’s novel, W.E.B. Du Bois commented,

It is all still a petty, silly matter of no real importance which another generation will comprehend with great difficulty. But today, and in the minds of most white Americans, it is a matter of tremendous moral import. One may deceive as to killing, stealing, and adultery, but you must tell your ‘friend’ that you’re ‘colored’ or suffer a very material hell fire in this world, if not the next.”

Rather than animosity towards interracial relationships disappearing, the Loving case, thirty-eight years after Du Bois’s review, proved that interracial relationships still encountered resistance.

100 Rifles debuted in the middle of this history and among a slew of novels during the 1960s and 1970s that explored the ways, as Karla F.C. Holloway notes, “interracial marriages and/or sexual relationships are contemporary conflicted sites.” These novels include works such as John A. Williams’s The Angry Ones (1960), Ernest J. Gaines’s Of Love and Dust (1967), Frank Yerby’s Speak Now (1969), Alice Walker’s Meridian (1976), Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979), and more. Actors Jim Brown and Raquel Welch’s on-screen relationship in 100 Rifles needs to be read within the historical context that reaches back even before Larsen’s Passing and into the present, and we need to consider its place among the contemporaneous small screen kiss between Nichelle Nichols and William Shatner in Star Trek in 1968.

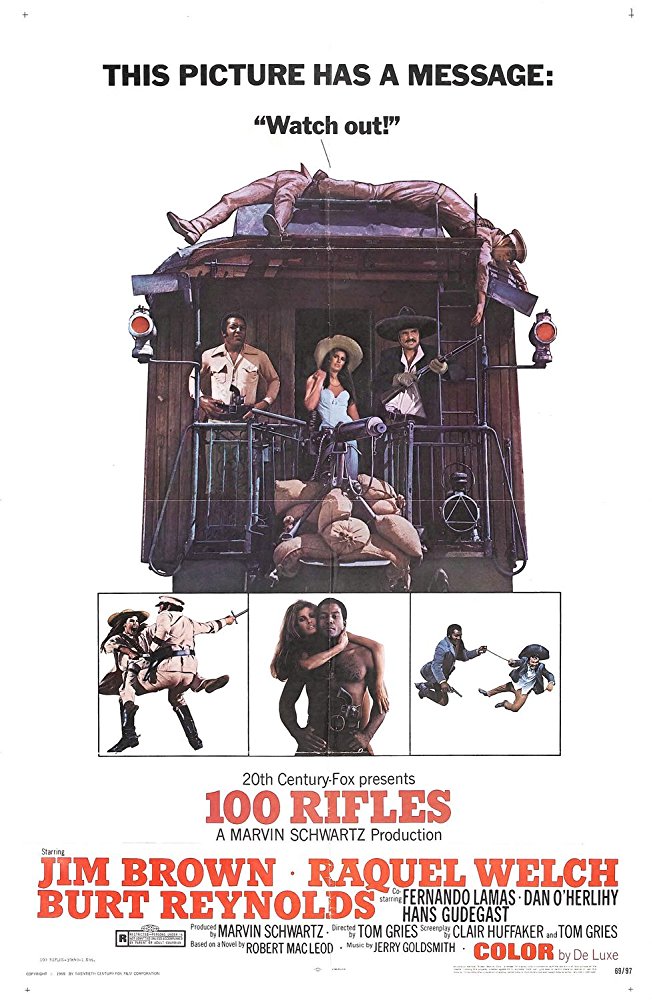

Just as speculative fiction like Star Trek uses the veneer of the genre to comment on the contemporaneous moment, westerns do as well. Stanley Corkin argues that we should read westerns from the 1950s and 1960s as metaphors that explore the United States both nationally and internationally. As such, we must view 100 Rifles as a commentary on race at the end of the 1960s, a year after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and a year after the Summer of ’68. Through this lens, the film provides a critique of the cultural milieu it initially appeared within; in fact, the trailer blatantly states, “This picture has a message.”

According to Sergio Mims, Jim Brown’s performance in 100 Rifles, “heralded the emergence of the black male action hero.” Mims discusses Brown’s portrayal of a strong character and the interracial relationship between his character and costar Raquel Welch’s Sarita. Along with Sidney Poitier, Jim Brown, as Zachary Ingle notes, “bore the same burden as Jackie Robinson” did when it came to deconstructing stereotypes.

Rather than pitting cowboys against Native Americans, the villains in the film are Mexicans, and by extension the white American Steven Grimes (Don O’Herlihy), and the heroes are a Black sheriff, Lyedecker (Brown), the Yaqui-Anglo, Joe Herrera (Burt Reynolds), and a Yaqui revolutionary, Sarita (Welch). Together, they confront and defeat the Mexican General Verdugo (Fernando Lamas) and the American Grimes who seek to eradicate the Yaqui Indians so the railroad that Grimes works for can proceed throughout Mexico.

Instead of having white, Anglo characters as the protagonists of the film, 100 Rifles focuses on resistance from “the Other” as Lyedecker, Herrera, and Sarita fight back against the representatives of colonial advancement. This reversal becomes apparent from the outset. When Lydecker tracks the bank robber Herrera to Sonora, both men are captured by Verdugo. Herrera stole $6,000 from a bank in Phoenix to buy 100 rifles for the Yaqui resistance.

While the film comments on the effects of colonization and racism in the characters of Verdugo and Grimes, the interracial relationship between Lyedecker and Sarita presents a template for social progress. When Sarita rescues Lyedecker and Herrera, they return to a village to regroup and rest. After Verdugo and his men find the village and burn it to the ground, Sarita dresses a wound that Lydecker receives during their counterattack against Verdugo and his men. After she cleans his wound, Sarita kisses Lyedecker. He grabs her by the waist, pushes her back against the wall, and passionately tries to kiss her. Sarita fights back, repeatedly screaming, “No! no! no! Please, not like this. Not with you.” Her response, along with Lyedecker’s forceful attempts to kiss her, foregrounds the fears that white audiences might have of a Black man and a white woman together and the preconceived stereotypes of Black men as being sexually aggressive. She viscerally tries to push him away, and rather than continuing with his pursuit, Lyedecker acquiesces, rejecting the stereotype of Black men as sexual brutes who want nothing more than to be with white women.

The two exchange a look, Sarita walks away, and Lyedecker follows her, grabbing her gently by the waist. He gently undoes the back of her bodice, turns her around, and the two passionately kiss as they fall on the bed embracing one another. When they enter the bed, the scene lasts for about a minute, showing Lyedecker’s hands on Sarita’s back, and ending with Sarita’s hands grabbing Lyedecker’s fervently. The scene initially rejects the stereotype, takes a beat, then replaces the stereotype with an image of Sarita and Lyedecker in a consensual embrace that has all of the hallmarks of silver screen romance. This scene caused a stir at the time, for obvious reasons.

Later, Sarita calls Lyedecker into a house. As Lyedecker stands against the wall, she bends over the fire and tells him, “Your supper is almost ready.” Here, we see a domestic image of the couple, getting ready to sit down to meal, even amidst the fighting and turmoil that surrounds them. “Lyedecker,” Sarita says before they begin, “you are my man.” He looks back, lovingly, and tells her, “You know you gotta be careful for a thing like that.” She responds by telling him she does not have to be careful because, as she says, “I am your woman for as long as you want me.” She asks, “Do you want me?” At this, Lyedecker grabs her arm, and it appears as if he will kiss her; however, he draws her close and embraces her in a hug.

Unlike the previous scene, this exchange solidifies the relationship, highlighting the fact that Lydecker and Sarita can love one another. Along with their love, the film also shows that their relationship can fight back against the representative powers that seek to keep them apart and in subjugation because of their respective ethnic backgrounds and the color of their skin. Coming on the heels of Loving v. Virginia, we must read the onscreen relationship between Lyedecker and Sarita in relation to contemporaneous debates over interracial relationships and the fears that some attach to them. 100 Rifles subtly obliterates these fears through deconstructing the stereotypes and showing, albeit briefly, a budding, loving interracial relationship in the form of Sarita and Lyedecker.

We need to read Lyedecker’s and Sarita’s relationship through the lens of the period and also through the lens of contemporary America. We need to consider it alongside Nichols and Shatner’s kiss, especially considering its place as the first interracial sex scene in a film. We also need to remember 100 Rifles and the progress that has occurred over the past fifty years after Loving because interracial marriages, according to a recent Pew Research Center report, have risen “from 3 percent in 1967, to 17 percent in 2015.” However, there are still those who oppose such unions. That number, however, has dropped drastically “from 63 percent in 1990, to 14 percent in 2016.” While progress has taken place, more needs to occur, and Lydecker and Sarita’s budding celluloid romance presents a way forward.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.