BlackPast and the World: Visualizing a Black International Network

*This post is part of our roundtable “Digital Black Atlantics.”

For historian Paul Gilroy, the Black Atlantic represented the notion of movement across the Atlantic, with the passages as places where ideas and cultures are transferred between people and are taken to other places, where they are continuously reformed and passed on again. Through movements, mobilities, transformations and appropriations an international (or even transnational) Black intellectual networks have been created, and are still being recreated daily. Therefore, the dynamic interplay of different forms of connectedness that are explored within studies on the Black Atlantic, and subsequently the broader field of the history of the Black diaspora, holds a particular potential for the mapping or otherwise visualizing of Black intellectual networks.

The rise of digital humanities as an established field especially offers great opportunities for the study of the geographical distribution of people and organizations or the dissemination of Black intellectual thought. Furthermore, digital methodologies can also provide us with new insights on subjects that deserve more of our attention, not only highlighting biases and certain knowledge gaps but also calling attention to new connections or dynamics that are otherwise difficult to notice. These methodologies inform us about knowledge systems of the past, and also reveal current trends in the dissemination of knowledge about global Black history.

This contribution to the forum on the Black Digital Atlantic discusses the outcomes of an experimental visualization project on the connectedness between people, organizations and events across the Black Atlantic, derived from the resource database of BlackPast.org (hereafter: BlackPast). Nowadays, online databases are profoundly influential in determining access to and information about the world, the past – and the history of the Black diaspora. BlackPast is an online platform dedicated to improving popular knowledge on African American history and Global African history by collecting resources and materials and making them easily available. The database plays an important role in informing the wider public about Black history, as can be seen in the viewer statistics.

Although often stressing its role as “Google” of African American History containing over 10,000 pages of information in different subcategories, BlackPast continuously emphasizes that it also provides a wide array of reference information on people, places and events in broader global African history. This ‘transnational/global’ image of BlackPast as “the single largest free and unrestricted resource on African American and African history on the internet today”, is further emphasized by stating the involvement of a “volunteer staff of twelve and nearly 500 volunteer contributors from six continents” who maintain the database. One part of the website is also specifically focused on “Global African History,” containing “short descriptions of individuals, places and events which have contributed to the shaping of African American history.”

However, as this visualization project has revealed, this relationship between African American history and the rest of the world, as portrayed by BlackPast in the “Global African History” section on their website, often proves to be rather one-sided. Furthermore, through the use of digital tools this project has revealed some interesting opportunities for studying relationships and dynamics in Black international networks, which deserve further scholarly attention.

I designed this visualization project in order to assess the use of digital tools for research on the history of Black international networks. I took entries on Ethiopia as a starting point for the collection of my dataset. Because of the country’s status of independent and sovereign African nation, Ethiopia has taken up an important place in the imagining of Black international, or pan-African efforts. As a result of this status, I expected that the source availability surrounding Ethiopia would reflect a global Black network. By clicking on the country of Ethiopia on the “Map: BlackPast and the World” section of BlackPast, all data on the website tagged “Africa-Ethiopia” shows. The results show 90 encyclopedia entries, categorized in descending order from the most recent posts (2021) to the oldest (2007). These entries contain information on specific people, organizations and events linked to Ethiopia.

Using these results I started with the oldest posts, and focused only on the entries of individual people born before 1945. I noted information on someone’s sex, place and date of birth, place and date of death, affiliated organizations and important events someone attended. In the end, this visualization project consisted of 83 people (of which 65 men and 18 women), linked to 47 groups, and 32 events. To be able to explore the mobility of these people, and possibly map crossings or interconnections that would otherwise remain rather hidden, I also included remarks from personal travel accounts in my data entry.

In this exploratory project, all gathered BlackPast data was processed in “nodegoat,” a web-based research tool to build datasets and analyze the spatial, relational and diachronic elements of your data. An analysis of the entered dataset revealed some interesting insights in 19th and 20th century Black international connectivity on the one hand, and the source biases of BlackPast on the other.

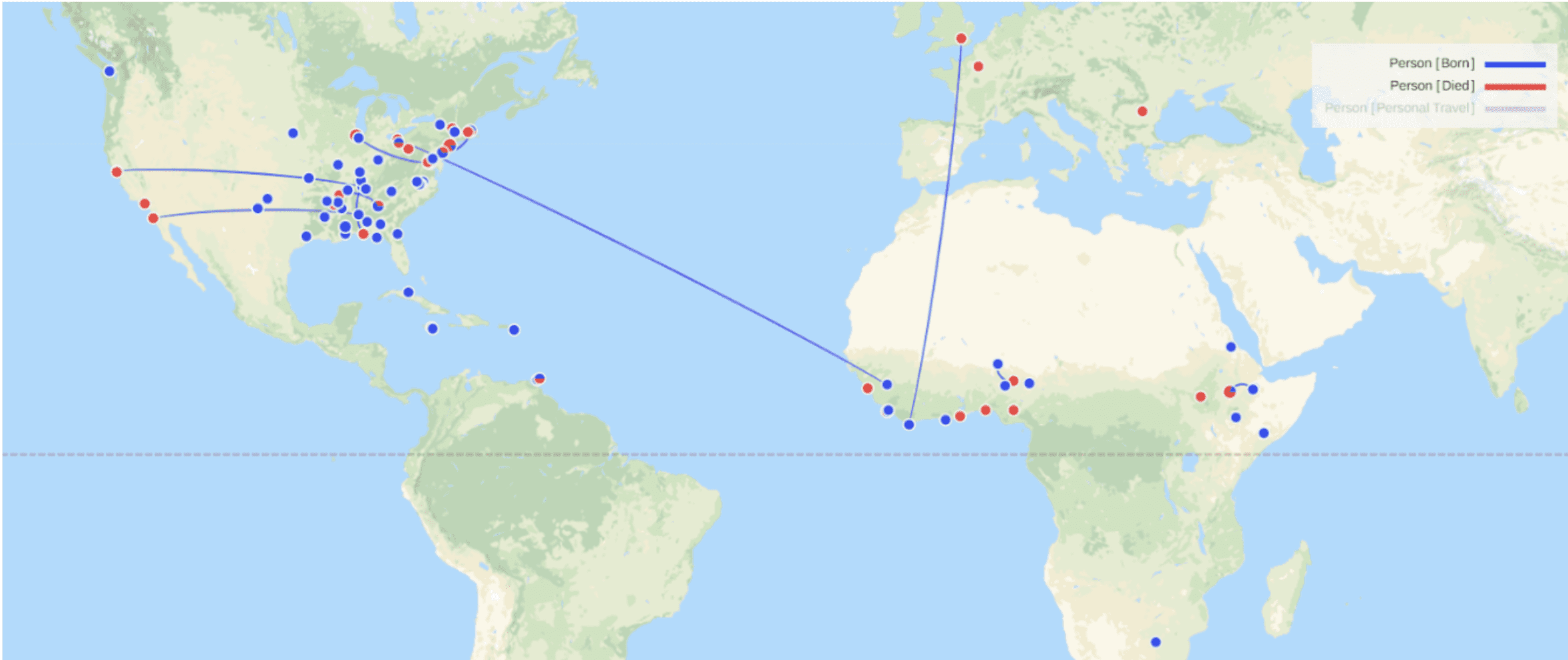

Although this figure is still messy and obscures the details of this network, it conveys information on the extent and number of connections distributed over the world (see Figure 1). Something that can already be seen quite clearly, is that the number of connections between certain areas are higher than between others. Most notably, stemming from Ethiopia this visualization only shows a pull to western Europe and North America’s west coast, while other connections seem to originate in North America. As this dataset is derived from the Ethiopian section of BlackPast’s encyclopedic entries, this is contradictory of what one might expect.

Examining the dataset further, we can see that the place of birth and place of death of the people involved in this “Ethiopian” network, as included in the BlackPast’s source base, are actually mostly born in North America (see Figure 2).

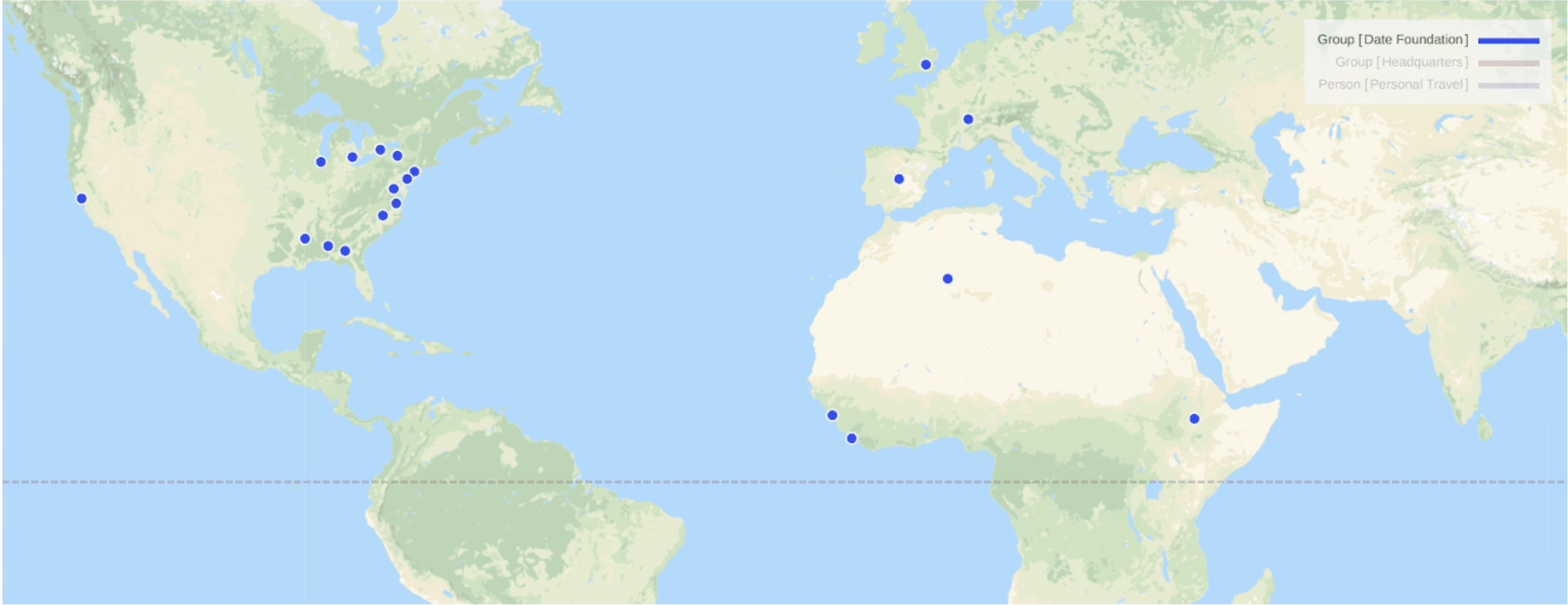

This source bias is therefore also reflected in the organizations and events these people are associated with, as can be seen in the following two figures which are almost identical (see Figure 3 and 4).

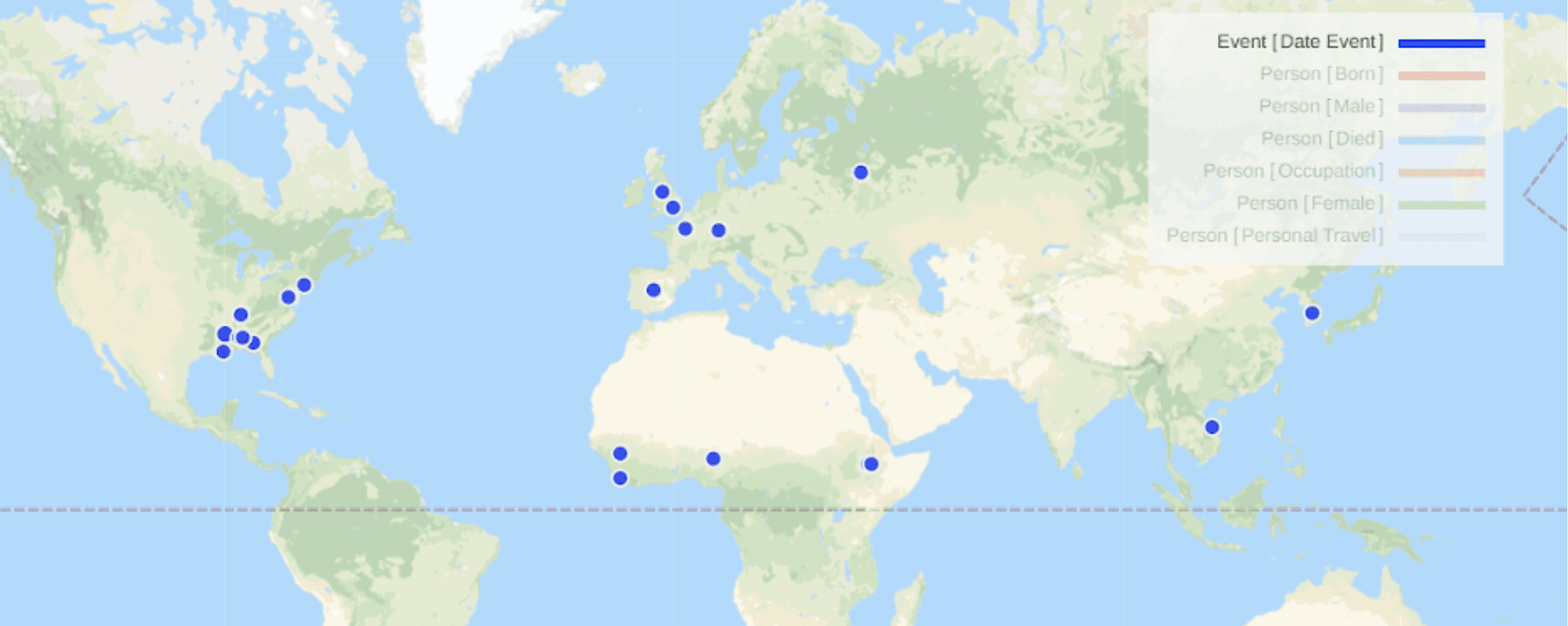

If we divide this network in male and female clusters (see figure 5), we can see the discrepancy of representation between men and women in the used source base. In our dataset of 83 people there were only 18 women opposed to 65 men, a meagre 22%.

Mapping and visualizing the spatial dimensions of organizations can clarify the connections or dynamics between different organizations or events and reveal possible overlapping pathways. Contrarily this method can also highlight a very different geographical focus or different network base. By focusing on specific organizations, one can discover the geographical pull of some sites over others. In the entries of the four people in my dataset that were connected to the establishment of the Organization of African Unity, no travel accounts to the United States were mentioned, but instead connections with Europe and other African countries took place (see Figure 6). Although these four people are not necessarily representable for a larger trend of people’s mobility, this visualization is an example of the possibilities of using digital tools to discern this kind of information.

This project was set up to explore the opportunities and pitfalls of using digital tools to visualize different aspects of Black international networks and connectivity across the Black Atlantic. Throughout this project, I developed interesting insights in the ways digital tools can be used to explore certain subject matters within the study of Black international networks. Although one should be very careful not to include too much information into one dataset – as to make sure particularities are not obscured by an overload of information – the use of digital tools provides valuable insights in dynamic relationships that are less easily conveyed through written texts, such as connectivity through mobility and networking. Maps can more easily reveal trends like pulls to certain areas, countries or cities, while visualizations of network analyses can convey links between people, organizations and events that would otherwise remain more obscured. As digital tools allow the user to cluster people by using filters or by constructing additional variables, datasets can be easily restructured to analyze differences in trends, such as between sex or nationalities.

Furthermore, this project engaged with the difficulties of source bias and the importance of its recognition, not only when making use of such databases for academic purposes, but also in regard to the dissemination of knowledge to the wider public. Even though BlackPast’s database is of paramount importance in the effort to inform a wider public on African American and global African history, we have seen that its sources show great geographical and gender biases. As various parts of BlackPast’s claims seem to emphasize its truly ‘global’ nature, these biases are something to take into account for both scholars and the wider public when consulting the site’s content.

Therefore, the use of digital methods depends on a fine line of adding just the right – and the right amount – of data to open up new perspectives on a subject matter, and this has to be done in a very structured manner for it to convey new information. Nevertheless, digital tools such as nodegoat hold great potential for the visualization of connectivity and mobility that plain text can not convey as well as digital methods can. With digital humanities gaining ground and getting more refined by the day, there is a bright future for interdisciplinary collaborations in studying the history of the Black Atlantic.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.