The Life of Pauli Murray: An Interview with Rosalind Rosenberg

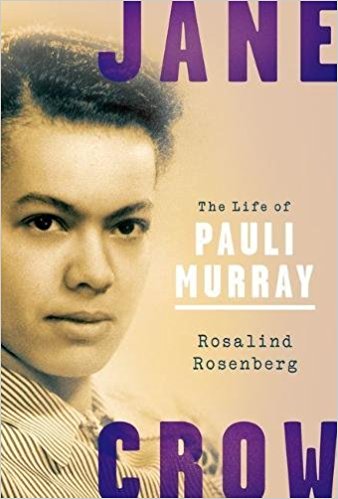

In today’s post, Alyssa Collins, PhD candidate in the Department of English at the University of Virginia, interviews Rosalind Rosenberg on her new book Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray, which was recently published by Oxford University Press. Dr. Rosalind Rosenberg is Professor Emerita of History at Barnard College, where she joined the faculty in 1984. Professor Rosenberg specializes in American history with a focus on women’s, social, and legal history. Related to her most recent book, she is the author of “Conjunctions: Race and Gender in the Work of Pauli Murray” in the Journal of Women’s History (2002), Divided Lives: American Women in the 20th Century (1992), and “Pauli Murray and the Killing of Jane Crow” in Forgotten Heroes From America’s Past (1998) amongst many other publications. Professor Rosenberg is also a member of the Executive Board of the Society of American Historians.

Alyssa Collins: Tell us a bit about how you came to this project. What are some of the factors that motivated you to write a biography of Pauli Murray?

Rosalind Rosenberg: I had never heard of Pauli Murray, much less considered writing her biography, before I met Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1974. Ginsburg was then the first tenured female faculty member at Columbia Law School; I had just taken a job in the Columbia history department. In addition to teaching law, Ginsburg worked on women’s rights cases at the ACLU. By the time I met her, she had persuaded the Supreme Court that the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, passed after the Civil War to protect the rights of African Americans, should also be understood to guarantee the rights of women. As a young feminist, I was impressed by Ginsburg’s success. As a historian, I was curious to know what had inspired her to argue that gender discrimination was analogous to race discrimination. The answer was Pauli Murray.

Murray became a staple of my courses in women’s and legal history, and I included her as a central figure in my book, Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century (1992), but I did not consider writing her biography until the mid-1990s when her papers were opened to researchers at the Schlesinger Library, Harvard University. Historians often lament the dearth of archival material on Black lives, so I could hardly contain my excitement when I discovered that Murray had left more than a 135 boxes of private papers and photographs, mostly her own but also of family members going back to the Civil War.

Collins: Tell us more about the process of conducting research for this book. What were your sources, methods, and methodologies? What did you find most interesting or surprising during the research process?

Rosenberg: When my career began in the 1970s, young historians avoided writing biographies. We were looking for social patterns and structures. In this search, we were reacting against the “great man” theory of history – the idea that presidents and generals moved history. We were more interested in social movements than in individuals.

One other thing delayed my undertaking Murray’s biography. Murray wrote two memoirs, one, Proud Shoes, the history of her maternal ancestors going back to the early 19th century, and a second, Song in a Weary Throat, an autobiography. Murray seemed to have said everything worth saying in these books. But as I made my way through her personal papers, I realized that she had left a great deal out of those memoirs: most importantly her struggles over gender identity. Here was a person whose life, written with full attention to historical context, could illuminate the intersection of race and gender, as well as the challenges faced by someone growing up a century ago who felt more male than female. These were years when the term transgender did not exist and there was no social movement to support or help make sense of the trans experience. Murray’s papers helped me to understand how her struggle with gender identity shaped her life as a civil rights pioneer, legal scholar, and feminist.

Collins: One of the crucial aspects of your book is your discussion of Pauli Murray’s struggles with issues of identity. Can you tell us more about what you describe as her lifelong feelings of being “in-between”?

Rosenberg: Murray felt “in-between” in her race, gender, and class. Born to mixed-race parents in Baltimore, she was raised by her maternal grandparents and aunts in Durham, North Carolina. Pauli, who was darker than other members of her Durham family but lighter than the other children at the segregated school she attended, suffered the emotional whiplash of warnings at home to stay out of the sun to avoid looking “niggerish,” and tauntings at school for being too white, a “bastard.” This sense of color “in-betweeness” inspired her to attack racial boundaries as arbitrary.

From at least the age of eight, Murray also felt in-between in her gender. Identified as female at birth, Pauli believed that inside she was a boy. She insisted on wearing boys’ clothes, playing boys’ games, and doing boys’ chores. Fortunately, Pauli’s namesake, her Aunt Pauline, accepted Pauli’s in-betweenness. She called Pauli her “boy/girl.”

Murray also felt an in-between in her class. Her relatives included wealthy white planters and rich black businessmen, but she grew up in poverty, because her maternal grandfather, who had fought discrimination to serve in the Union Army and was wounded, gradually lost his sight and the ability to make a living. Her aunts’ salaries as teachers might have compensated for that loss, but the tightening grip of Jim Crow led to a sharp drop in black teachers’ salaries. Murray grew up knowing that she came from people who mattered, even if her immediate family was poor.

Collins: In the book you write about what Pauli Murray describes as her “confused world of uncertain boundaries” (2). Tell us about how you see this worldview as something that influenced her work throughout her life. Do you see this ethos aligning with what we now consider “intersectionality”?

Rosenberg: Murray spoke of her “confused world of uncertain boundaries” in the opening to her memoir Song in a Weary Throat. When I first read that book, I took her to be referring to racial boundaries and the boundary between the world of the living and the dead, especially the parents she lost as a young child. But as I came to know Murray better through her papers, I saw that “boundaries” referred also to gender. She always felt that the boundary between male and female was arbitrary, that everyone is male and female to differing degrees, and that some people (like her) might look female on the outside but be male on the inside.

Murray’s critical stance on boundaries made her especially sensitive to the ways in which those in power could use categories to oppress others. This sense of being subject to multiple arbitrary categories made Murray sensitive to the ways in which overlapping oppressions could be particularly harmful. In the early 1940s, while at Howard law School, she coined the term Jane Crow to convey the way in which the black men at Howard, who were acutely conscious of race discrimination and had come to law school to train to be civil rights lawyers, were oblivious to gender discrimination. Murray spent the rest of her life writing about the ways in which the intersection of race and gender discrimination resulted in Black women’s being doubly oppressed. Murray never used the term intersectionality, but her work anticipated this concept.

Collins: Your book covers the wide array of Murray’s work as lawyer, scholar, activist, and Episcopal priest. Can you tell us more about these shifts in careers? What are the factors that motivated Murray’s decision to move into more religious work in the latter part of her life?

Rosenberg: Faced with discrimination and economic uncertainty, everyone in Murray’s family developed multiple talents. But discrimination and economic uncertainty explain only some of Murray’s career changes. In 1959, having finally found a high-paying job in a prominent, liberal law firm in New York, she resigned to take a lower-paying position as a law professor at the newly formed law school in Ghana. It was never enough for Murray to find work that paid well; work had to be meaningful; it had to advance the cause of human rights. Once she had made headway in one area, she tended to lose interest and move on to a new frontier.

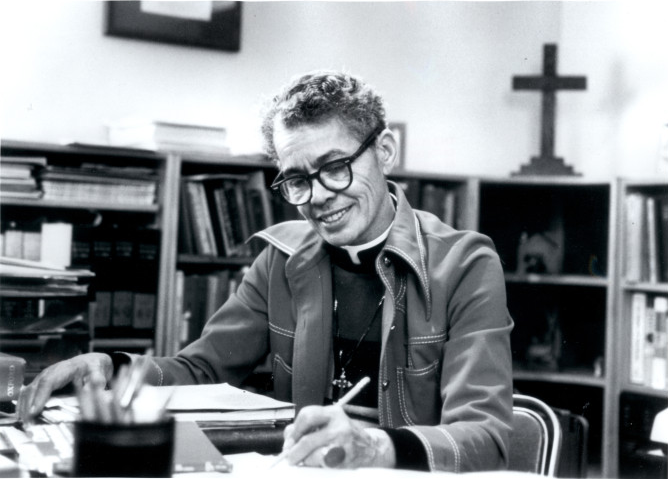

Only two years after winning tenure as a professor of American Studies at Brandeis University in 1971, Murray resigned to enter an Episcopal Seminary to train for the priesthood, even though the Episcopal Church barred women from ordination. Murray became the first black female Episcopal priest, in part, to right what she saw as the church’s wrongs against women. In her sermons, she sought to redirect theology away from its patriarchal emphasis toward what she believed to be Christianity’s core teaching: that in Christ there is no black or white, no male or female. Theology was Murray’s last frontier.

Collins: What insights do you think Pauli Murray’s story offer on current movements for equality and social justice? What lessons can we all learn from Murray?

Rosenberg: Living as we are in the midst of a powerful backlash against civil rights and feminism, we need to know the story of Pauli Murray for at least two reasons. First, we need historical perspective. Murray’s life demonstrates that today’s backlash and the struggle against it have deep historical roots. They date back at least to the early nineteenth century, when Murray’s maternal grandfather fought against slavery. From him Murray learned that the history of the civil rights movement was one of advances but also of setbacks. As a young child, Murray learned about the Post-Civil War Amendments that protected the rights of blacks, but she grew up under Jim Crow. As an adult, she became a lawyer, but her search for work ran afoul of McCarthyism, which took particular aim at blacks, women, and homosexuals. Murray’s story testifies to the importance of perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Second, Murray’s life teaches us that society’s outsiders often have the most important insights. Those outsiders may be immigrants, or they may be native-born citizens who are marginalized by poverty, religion, race, gender, or disability. This outsider status can give them an angle of vision that allows them to see what others cannot. Murray was the quintessential outsider and her vision changed our world.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.