Blackness, Pessimism, and the Human

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture / NYPL Photographs and Prints Division.

There is a specter haunting black studies, black freedom struggles, humanism, and the politics of recognition. This recalcitrant specter currently dons the name “Afro-pessimism.” Its ghostly presence refuses to be exorcized or conjured away by invocations of racial progress and the promise of American democracy, or by appeals to iconic black figures (like the Obamas) who supposedly demonstrate that black bodies have been included, albeit uneasily, within the elastic domain of the Human. Afro-pessimism is indebted to authors like Frantz Fanon, Saidiya Hartman, and Hortense Spillers, and contends that there is a fundamentally antagonistic relationship between blackness and the Human. While the pessimist can acknowledge change and variation over space and time within the racial order, s/he denies that these factors alter the constitutive quality of the Black/Human antagonism. The Human is a domain that will always mark black people as sub-human or not quite human. In what follows, I am not interested in corroborating or disproving the arguments put forth by the Afro-pessimist. Hasty subscriptions to or reflexive dismissals of Afro-pessimism tend to miss an opportunity for patient, receptive engagement with the stakes and implications of this burgeoning discourse. Consequently, I am more interested in tracing the widespread assumptions and tenacious commitments—occasionally shared by black studies, liberal democracy, and critical theory—that the Afro-pessimist puts into play, exposes, and disconcerts.

What exactly is Afro-pessimism? Who are its proponents? While several authors currently identify with the Afro-pessimist position (Jared Sexton and Calvin Warren, for instance), Frank Wilderson has provided the most acute and well-recognized definition of the term. In his incisive text Red, White, and Black: Cinema and the Structure of US Antagonisms, Wilderson writes, “The Afro-pessimists are theorists of Black positionality who share Fanon’s insistence, that though Blacks are sentient, the structure of the entire world’s semantic field…is sutured by anti-black solidarity” (58). According to this description, the domains of meaning, grammar, and law are defined over and against the black body, which came into being through the gratuitous violence of kidnapping, the Middle Passage, and slavery. The Afro-pessimist contends that humanism incorrectly assumes that all forms of suffering can ultimately be redressed and overcome through the grammar of rights, respect, and compassion. To the contrary, Wilderson contends that humanism cannot acknowledge “an object who has been positioned by gratuitous violence—a sentient being for whom recognition and incorporation are impossible” (55). In other words, humanism is blind to its own condition of possibility because the coherence of the Human relies on the exclusion of blackness. There is no grammar for black suffering within humanism because humanism treats suffering as contingent and resolvable through the process of assimilation. This familiar stance cannot register the constitutive quality of anti-black violence, which is a condition that can only be eliminated, according to Wilderson, by bringing about the end of civil society as we know it.

Perhaps what is so powerful—attractive to some, repulsive to others—about Wilderson’s formulation is how it compels us to re-examine pervasive assumptions about race, black struggles for freedom, history, and human recognition. For clarity, I break these assumptions into three parts: the politics and grammar of recognition, the Human as a site of racial transcendence, and the relationship between structure and agency.

It is very difficult to talk about the strivings of excluded groups apart from the politics of recognition. Persecuted communities are required to articulate their grievances and aspirations through the language of recognition, a predicament outlined by the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel. In his oft-cited description of the Master/Slave relationship, Hegel suggests that antagonistic, hierarchical relationships can be overcome through struggles for mutual recognition. Mutual recognition is the capacity of two or more people to see themselves as participants in a shared ethical and political life. Instead of seeing each other in a hostile, contentious manner, mutual recognition occurs when individuals see themselves in others and vice versa. This mutual acknowledgement is possible because of collective norms and practices, and the general realization that individual lives depend on the broader social world for survival, affirmation, and ethical formation.

While this sounds encouraging, Wilderson maintains that this domain of mutual recognition depends on a fundamental barring of black bodies. He claims that “Whereas Humans exist on some plane of being and thus can become existentially present through some struggle for, of, or through recognition, Blacks cannot reach this plane” (38). This plane of recognition is anti-black. Eric Garner experienced this throughout his life and in his last breath. His chokehold killing at the hands of police officers was deemed legal and appropriate, indicating a long-lasting antagonism between the law and blackness (the law reproduces itself through the surveillance and containment of blacks). Some even refused to blame Garner’s death on the violent actions of the police officers and instead blamed his obesity, demonstrating how the “excessive” black body eludes everyday practices of recognition and compassion.

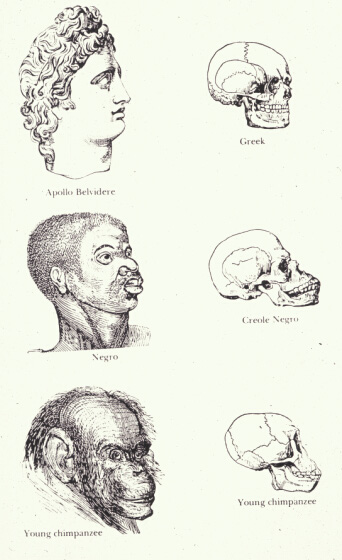

The assumption about the viability of mutual recognition, which is contested by the pessimist, dovetails with enduring desires for racial transcendence. Whether one believes that we live in a post-racial world or not, the transcendence of racial difference supposedly occurs when we embrace our common humanity. According to this view, race is merely an illusory social construct that hampers people’s ability to acknowledge similarities across racial lines. When someone claims, “I am part of the human race” or “All lives matter,” the assumption is that the Human is a universal, all-accessible category. In other words, the Human is an inclusive category while the invocation of blackness is divisive. Following Fanon, the pessimist reminds us that the Human is also a divisive modern construct that emerges alongside racial formations. More specifically, the qualities of the ideal Human—reason, freedom, property, accumulation—are defined in opposition to certain kinds of undesirable characteristics and positions—wildness, excess, slavery, and the vagabond. Consequently, the Human that imagines itself settled and standing his/her ground (George Zimmerman) is justified in attacking a black body that seems out of place (Trayvon Martin), that is wandering aimlessly and “up to no good.” While Wilderson can concede that the Human, as the domain of recognition, has assimilated formerly unrecognized groups and communities, he suggests that the very process of becoming Human requires an acceptance of anti-blackness. Therefore, there are structural limitations to the inclusivity of the Human.

The very language of structures rubs many people the wrong way. In addition to diminishing the significance of history and context, the notion that the social order is organized by constitutive constraints denies agency. We live in a world that celebrates the self-willing individual wherein the self is depicted as the ultimate source of its own success or failure. Whether we read self-help books or listen to prosperity gospel sermons, the message is that life is filled with infinite opportunities and a person’s ability to realize these abundant possibilities depends on that person’s attitude, courage, work ethic, and so forth. More sobering views of agency suggest that while our actions are constrained by norms, these norms undergo transformation through subversive performances of the norm.1 For the pessimist, the potential for subversion and transformation runs up against inveterate limitations. This constrained agency happens within a social order made possible by anti-black violence. When Wilderson uses terms like “Black” and “Human” in capital letters, he registers a social world that positions, marks, and manages bodies in a relatively reliable, systemic manner. While difference and variation exist within the category “Black,” Wilderson contends that these differences do not diminish the incompatible non-relationship between Blackness as a position and the sphere of the Human. This antagonism, while it emerged historically, has become part of the fabric of the world. One might wonder why we should even write, contemplate, and diagnose these matters if there is no possibility for altering this predicament. In light of Wilderson’s lifelong activism, the Afro-pessimist stance does not necessarily lead to resignation but can prompt radical theoretical, aesthetic, and political efforts to end the world as we know it.

There is much in the Afro-pessimist position that awaits further elaboration. As the pessimist haunts contemporary discourse and practice, lingering questions disturb the pessimist. What happens to intersectional approaches when gender, class, and citizenship concerns are overshadowed by the Black/Human non-relationship? Is blackness exclusively determined by anti-black violence? If not, what kinds of practices have enabled blacks to endure and subsist in the abyss of social death? Does the Human/Black binary ignore how certain forms of blackness have been uneasily incorporated into the sphere of the Human to perpetuate the logics of capital, empire, and settlement? While these questions hint at limitations in Afro-pessimism, they do not dampen the force with which the pessimist frustrates basic assumptions and fantasies about race, recognition, and human belonging.

- The gender and literary critic Judith Butler endorses this view of agency. See for instance The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. ↩