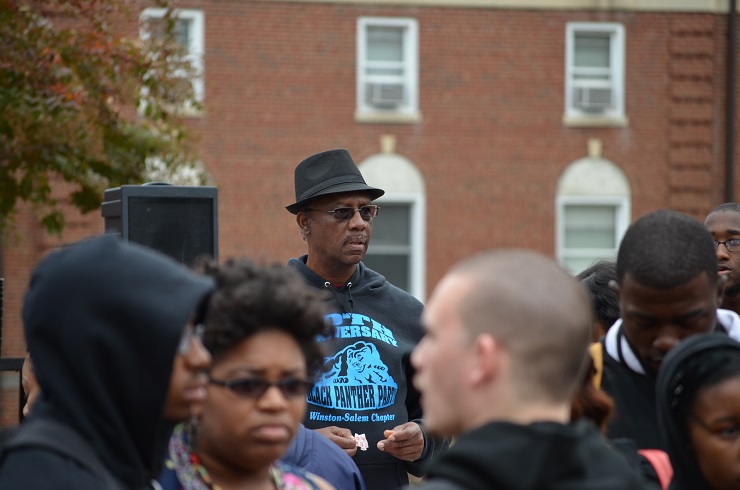

The Black Panther Party of the South: An Interview with Larry Little

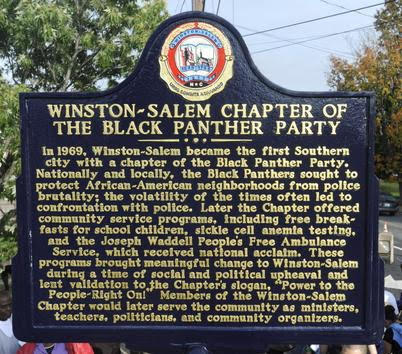

Larry Little’s story doesn’t fit into the dominant narrative of the Black Panther Party (BPP) as an organization limited to major cities in the West and North. Born and raised in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Little’s leadership of the Panthers in his hometown helped to catapult the chapter to national prominence, earning it a reputation as the most successful and influential BPP cadre in the South. In 1977, Little was elected to Winston-Salem’s Board of Aldermen, following a close and disputed electoral defeat in 1974. Little is now an associate professor of political science at Winston-Salem State University. The following is an edited excerpt from an interview I conducted with Little in August 2014.

Larry Little: In 1969, a group came over from Greensboro saying that they were associated with the Black Panther Party. One of the young men’s name was Eric “Pascha” Brown. He had played basketball with Lew Alcindor, who later became Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and he was playing basketball at North Carolina A&T. He had some affiliations with the Party in New York, so he tried to get a chapter started in Greensboro. They had an impression on us, coming over with the black uniforms on. They carried shotguns, rifles, and I was impressed with that.

They announced they were going to have a little community interest meeting in a couple of days. I went to that interest meeting and I’ll never forget what they said: “We want you to help sell our newspapers.” The first edition of the Panther paper that I sold was a picture with Malcolm X on the front. It was in May, and Malcolm’s birthday is May nineteenth. Then I decided, “Hey, I want to throw down with this.” But we later found out that the national office in California was not recognizing anything in North Carolina or in the South, really.

The national party said, “Look, if you want us to recognize you, someone has to come from there to California to go through our extensive training.” I was nineteen years old and I had quit my job working from eleven until seven and I had quit college at Winston-Salem State so I could be in the Panthers. And they said, “Well, Comrade Brother, you don’t have a job. You don’t have a family to support. Would you consider going to California?” Of course, I was delighted to go.

When I went to California, it was really awesome, an awe-inspiring experience. I got a chance to go to the county jail to visit with Bobby Seale. But the highlight of it all was getting a chance to meet and talk and communicate with Fred Hampton, who was the chairman of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party. It was very interesting. Fred Hampton did not want me to come back to North Carolina. He said it would be too dangerous. He said, “Too many Panthers will be killed before we can get a base in the South.”

He said, “Brother, we have a base in Chicago now. Only one Panther has been killed.” He said, “Fifty Panthers will be killed before we can get a base in the South.” I said, “But the majority of black people are in the South, Comrade.” And he said, “Well, we’re going to be in the West, the Midwest, the Northeast, and then we’ll extend into the South.” I said, “I think that is not the strategy for the Party.” And he said, “Well, the Klan is so strong in the South. There is no difference between the Klan and the police.” And I said, “But we’re prepared.” And I talked to Bobby and went to the county jail, and ultimately they relented.

I was there for several months. I would walk from the office in Berkeley, California, over to Oakland, selling newspapers, and sell the papers the whole way back. There was no transportation; we just walked. I imagine it probably was a ten-mile walk or more, back and forth. And we would be in political education classes constantly. You got a chance to see and meet people and revolutionaries from around the world who were coming to California to the national office of the Party, people from the Pan Africanist Congress in South Africa, like David Maphgumzana Sibeko.

The key thing for me was getting a chance to read the different works that we were required to read, like quotations from Mao Zedong, which I had done in Winston-Salem before I even joined the Party, and having political education classes with Masai Hewitt, who was our minister of education, and David Hilliard, who was the chief of staff. Eldridge was out of the country at that time.

They eventually said, “Brother, you have met all of our expectations. We’ve tested you in a lot of ways, and you’ve risen to the occasion.” And then David said, “We’re going to send you back to North Carolina, and you’re going to be the coordinator of the chapter.” I said, “No, I really don’t think I should be, because we already have a structure in place, and I was like our lieutenant of information.” And they said, “But we don’t trust [the other Panthers in North Carolina]. We trained you.”

They also said that if people are going to consider themselves to be Panthers, they have to work for the Party 24/7. They can’t go to an eight-hour job, then come during their off-hours and work. They said, “Now, they can help the Party, but they will be considered community workers, not part of the Black Panther Party, or cadre.” When I came back and explained them to people, it seemed as if I was on a power trip and it was not received very well by a number of members. Some of them decided they would leave, but many said, “Hey, look, they’re killing us. They’re going through all these changes. We’ve got to dedicate ourselves, body and soul, to the cause of the revolutionary movement.”

Those who were not prepared—they had children, families to provide for, and the Party wasn’t paying any money. It was like we were all volunteers. We got not one ounce of compensation. It was not like you got any shoes, or you got money. You got nothing! You just got food to eat and a place to stay.

We just began to build the organization and we got a lot of brothers and sisters who really felt they wanted to be in the Party. A number of people left Winston-Salem State and came to the Black Panther Party, and they came from other universities too. Like Hazel Mack, who was at Shaw University, but she wanted to work with the Party in Winston-Salem. She was from Winston-Salem and she became our communications director and, you know, she’s gone on to do great things later. After she left the Party, she was the first woman elected SGA president here at Winston-Salem State, and now she’s an attorney. She runs the legal aid societies for northwest North Carolina and much of North Carolina, period.

At one point in Winston-Salem, we started a free ambulance service. In the ‘50s and early ‘60s, the black funeral homes ran ambulance services out of their funeral homes. They got out of that business. The county took over and they claimed that people were misusing the ambulance service, using it as a cab. They said, if you call an ambulance, and the ambulance attendants come to the scene, and they feel you’re not in an emergency situation, they would ask you to pay twenty-five dollars. If you didn’t have the money to pay, they’d tell you to call a cab. They misdiagnosed people’s conditions, and people died. So, we said, “This is crazy. This is a human right to be able to go to the hospital.”

Our ambulance service was named after Joseph Waddell, a Panther who was killed in Central Prison in North Carolina. They came into his jail cell, his prison cell, and threw eight cans of Mace and sprayed him down with five hundred pounds of water pressure and induced this twenty-one-year-old black male into a heart attack.

We look back on our time in the Panthers and say, “Boy, whew!” It’s amazing. Some of us didn’t survive that. Some came out permanently scarred. Some have been able to make adjustments in their life and continue to evolve and try to be relevant. But the ‘60s were—as Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities says, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” You’re doing things, you’re growing, you’re studying, you’re expanding. At the same time, you’re being arrested, and people are being killed. Whew! It’s a dichotomy. But it was all done to make America better.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I appreciate this article!!! Dr. Little was one of my first professors during my time at Winston-Salem State University. He was the first professor to believe in me as a young Black Woman, and thus push me to become a better woman, student, and advocate. If it wasn’t for his leadership I would’ve never had the courage to put my degree on the line when Trayvon Martin was killed, and hold a peaceful protest on our campus, nor would I have ran for Student Government where I won, nor would I have I graduated Cum Laude, and as a Honors Program Graduate after being a Student Athlete. His knowledge, bravery, and encouragement, caused me to do better, and rise to the occasion, when it came to speaking up for others, and now I have made a career of doing just that as a National Advocate for Foster Youth, representing North Carolina, and as a Case Manager at a local non-profit. I believe in celebrating people while they’re still alive, and Dr. Little is truly one of my heroes.