Ideas in Unexpected Places: Why a Marketplace Intellectual Life Still Matters

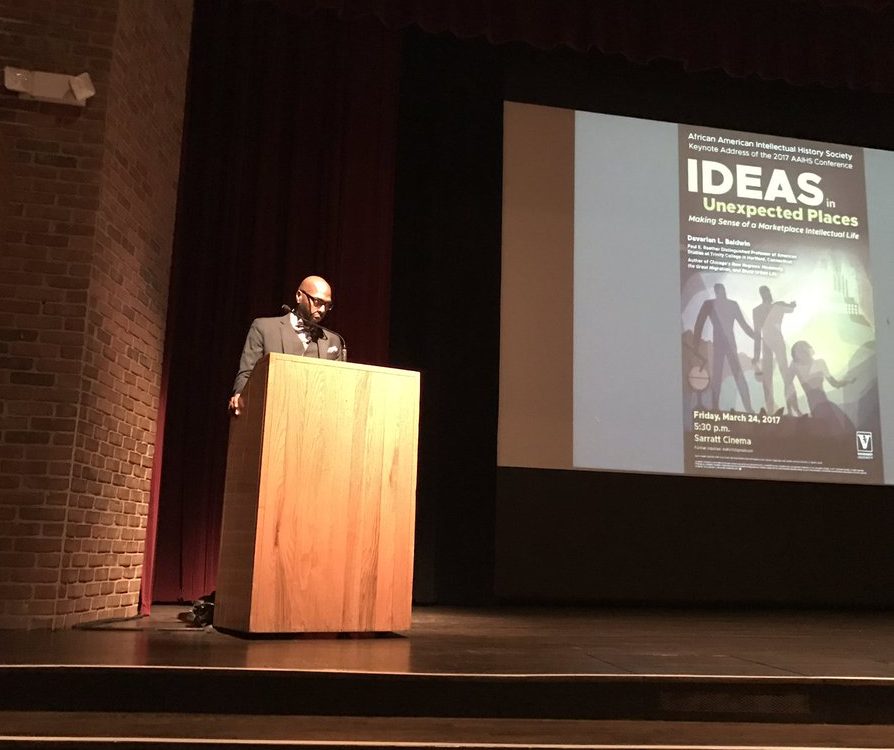

This post is a condensed version of Davarian Baldwin‘s keynote address at the 2017 AAIHS conference at Vanderbilt University.

***

I want to express what an honor it is to offer a keynote to you here at the African American Intellectual History Society’s second annual conference. The very legacy of this organization is historic in itself. Here we have mostly junior faculty assessing the limits of how the academy imagines and institutionalizes “intellectual history.” Instead of just offering critique, these young scholars moved forward to create a space where we can cultivate new directions and pathways within the field. It must be noted that this is no small feat, when the academy tells us that the only thing a junior faculty member should be concerned with is getting tenure.

In the spirit of this year’s theme “expanding the boundaries,” I am going to offer a bit of personal intellectual genealogy to explain how and why I needed to come up with the seemingly anachronistic idea of a marketplace intellectual life. I hope this bit of biography can serve as a useful primer for folks trying to think about how to do intellectual history differently, especially when our people’s stories have not been held within the traditional archives nor fully embraced by the likes of the Society of Intellectual Historians.

Therefore, this recounting of the “marketplace intellectual life” is a word of encouragement, a tough love laying down of the gauntlet to “Expand the Boundaries of Intellectual History;” a call for you all to never stop, no matter the challenge or dismissal, to never stop looking for new and innovative ways to both recover and capture how black people have produced, consumed, debated, and pushed forward ideas that could sustain us all.

Expanding the Boundaries of Intellectual History

Around 2001 I was doing what many young scholars just out of graduate school have or will do: I was trying to convert an unwieldy dissertation into a book that someone besides my committee might want to read. In what became Chicago’s New Negroes I was pushing hard to conceptualize this notion of a “marketplace intellectual life.” I wanted to explore the lives of Black migrants and their turn to urban consumer culture as a viable space of knowledge-making and political debate.

With a focus on Chicago’s historic black community, I organized my thoughts around the four areas of beauty culture, gospel music, filmmaking, and sport in the 1920s and 1930s. There I saw a powerful intersection between Black knowledge-making and consumer culture. Key marketplace intellectuals included the beauty culturist Madam C.J. Walker; independent filmmaker Oscar Micheaux; gospel blues musician Thomas Dorsey; and the sporting exploits of boxer Jack Johnson and baseball entrepreneur Andrew “Rube” Foster. For these migrants the creation, circulation, and debate over hairstyles and movie going etiquette did not confirm the “freedom” of the so-called free market. My concern was to reconstruct a critical moment when Black migrants used the consumer marketplace to challenge community tradition, rally against racial injustice, and yes, contest the dehumanizing effects of capitalism. I was fully inspired by examining these subjects of history etch out spaces of leisure that could help them think through the possibilities of a better world.

This discovery of a Black marketplace intellectual life was exciting and I sent my manuscript to the logical presses given the subject matter on Chicago. A well-known book series on the historical studies of urban America offered me a contract. However, in their comments the main series editor expressed serious reservations about my notion of a marketplace intellectual life:

I don’t see what differentiates an “intellectual” from anyone else who has ideas…I think the issue really involves the concept of intellectual history…yes we must consider all the realms in which ideas are created….But that doesn’t mean that the people who develop these ideas are intellectuals…I think Baldwin faces a difficult challenge in finding evidence that consumers really are intellectuals…”

To be sure, I could have made some revisions, pulled back on the claim that everyday consumers can produce an intellectual life. But this notion of a marketplace intellectual life was at the core of my vision. This idea wasn’t purely academic, it was personal. Where this editor saw a “difficult challenge in finding evidence,” I saw an abundance of everyday brilliance. I grew up witnessing a vibrant world of everyday people continually expanding the boundaries of intellectual life all around me.

A “Difficult Challenge”?

I grew up in Beloit, Wisconsin, a hardscrabble, small industrial town that included a tight core of Black factory workers, hustlers, Holy Ghost saints, and housekeepers sitting right on the Illinois-Wisconsin border.

In a Black community driven primarily by heavy industry, one’s class position was not determined by occupation but largely shaped by the factory where you worked; the higher wages at General Motors or Chrysler and the more modest opportunities at Frito Lay and Hormel determined your status. But underneath the smoke and soot, this factory life also powered a vibrant Black public sphere of churches, jukes, and taverns. Migrants cultivated social ties and clubs that sponsored fish frys, dances, and scholarships. And at Juneteenth celebrations, for example, every stripe of Prince Hall Mason, Eastern Star, military veteran, pop-up barrel barbeque business, dance troupe, and church choir served in prideful attendance.

This Black public sphere was always more than an escape towards frivolity because it cultivated an undeniable “world away” from the dictates of factory life, a place to shake off the coveralls and stand upright no longer as anonymous industrial cogs but as deacons, church mothers, big timers, auxiliary secretaries, and stars of the show. Dusty work clothes transformed into elegant gowns at Socialite Club fashion shows where the runway spilled out into the audience.

But I also saw in this Black public sphere deep thinking about the seemingly most visceral, everyday, fine-grained details of life. I witnessed vigorous intentionality and debates over worship practices, clothing and hair styles, processional formation, drink etiquette, policy gambling “dream books,” that were all…thoughtful.

All this to say that I faced no “difficult challenge” finding ideas in unexpected places.

The Marketplace of Ideas

The irony is that while scholars have remained skeptical of consumers as intellectuals, capitalists continue to see profit in the “marketplace of ideas,” with entrepreneurs being knighted “thought leaders” simply because they have achieved financial success. In Chicago’s New Negroes we have an equivalent convergence between ideas and industry seen today, but not one over-determined by the values of capital; an orientation that brings a radical or at least disruptive/alternative praxis to the marketplace.

When I think back to the gauntlet thrown down by that series editor who challenged the idea of consumers as intellectuals, I am reminded that my personal Black intellectual history tells a different story. Those Black migrants from Mississippi who made lives in Beloit weren’t just blank slates. No! They were the thought leaders who brought along their fight against Jim Crow, their designs on social life beyond the shop floor, their desires for both intimate and collective pleasure. They brought pre-existing systems of meaning to their marketplace.

In the same way that we denounce the lie that the internet radicalized Tahir Square or Ferguson or Baltimore or Flint, we testify today that technology is only as good as the people who were present. The people who saw Mike Brown’s body languish in the street. The people who bore witness to the life and death of countless unarmed youth guilty of “non-compliance.” The people who picked up the Molotov and the smartphone and thought through a way to take the materials of received knowledge and rework them into a new framework and new pathways to liberation. Because thinking through the possibility of another world is always within reach.

There is no question that this history of a marketplace intellectual life is confirmed in the present. My older colleagues couldn’t make sense of this praxis, but history has indicted their blindness. Certainly all of the young scholars affiliated with this new African American Intellectual History Society are leading the charge in new ways of thinking about music, sport, fashion, and visual culture as sites of community, politics, and, yes, ideas.

It may seem common sense now to imagine an expanded vision of how and where ideas are produced. But sometimes it is important, as historians of ideas, to consider “the world before”: the world, to paraphrase the great Michel-Rolph Trouillot, when notions like a marketplace intellectual life were “unthinkable.” To be sure, the marketplace is not a panacea, but at the same time it remains a vital site of struggle and a site of meaning-making, especially for those without access or the desire to enter the ivory tower or church pulpit. The point where ideas and industry meet is a space that demands our scholarly attention.

Brilliance, intellect, and the profundity and blueprints of possibility fester and grow firmly within the living archives of our full range of everyday experiences, no matter where these wellsprings are found…even in unexpected places.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I like this! Though I see two sides of the marketplace. On the one side are the Key marketplace intellectuals you have mentioned (I may expand the list to include recent men and women). But these are mainly the supply side intellectuals (Bishop Jakes, Didi, Tyler Perry, etc). On the other side of the marketplace are consumers (including many street poets and other intellectuals). And from schools to homes (computers) powerful people – whether intellectuals or not – are turning any space they can imagine into a marketplace (with ads that target even preschoolers). Where does this leave us

Thanks

James Oloo

@JamesAlanOLOO

Thanks for your comment James. First this was an historical study, so yes there are many contemporary examples (I mention the activist/intellectuals around Flint, Baltimore, and Ferguson for example). But I was actually coming at this from a different angles not folk turning any space into a marketplace but folks turning the marketplace into a site of ideas and politics…bringing ideas and ambitions with them and transforming ideas into action and more ideas, all never fully determined by the values of capital….so for good and bad folks like Shonda Rhimes or Alicia Garza as well as consumers of various blogs, music, and television screening parties, perhaps not intellectuals all but certain public spheres of discourse and debate.

thanks again,

dlb