Police Brutality and Racism in Germany

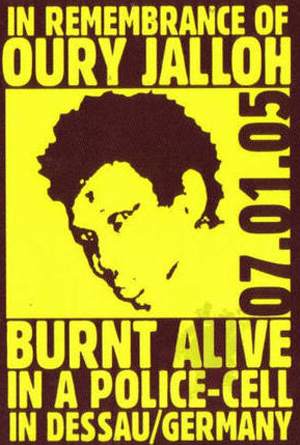

Oury Jalloh, a man in his thirties from Sierra Leone, had applied for asylum in Germany and was living in the small city of Dessau. Early on the morning of January 7, 2005, he was arrested for repeatedly asking city sanitation workers to place a call from their phone. He was detained at the local police station and questioned. Then, officers chained him by his wrists and ankles to the floor of a holding cell, and there, on a fireproof mattress, he burned to death later that morning. The fire ravaged the mattress and consumed Jalloh’s body entirely. According to officers, smoke alarms rang, signaling a fire, but they switched off the alarms, believing the system to be malfunctioning. Firemen had not been informed that someone was in the cell, so they must have been shocked when they found a man chained to the floor.

Friends and relatives were in disbelief. Reminiscent of Emmett Till’s funeral, they opened Jalloh’s casket at his memorial service to show the Dessau community the state of his charred body. His friends fundraised and organized a second autopsy of Jalloh’s body, which revealed a broken nose and burst eardrum, and later, it would reveal relatively low levels of soot in his lungs, which suggests he may not have been breathing deeply or at all when he died.

The state prosecutor declared Jalloh’s death to be a suicide and brought negligence charges against police. The supervising officer, eight years after Jalloh’s death, was issued a fine. Debates continue today as to why the investigation and prosecution were unconcerned with the possibility that Jalloh was murdered by police that morning in Dessau. Jalloh’s case, while it may sound particularly sinister, illustrates a pattern—a systemic failure for authorities to properly investigate police violence.

Jalloh’s case, over the years, has made national headlines, it has surfaced time and again, thanks to a group of committed activists, media allies and a large number of people who have contributed financially and otherwise to what has been long road towards an Aufklärung (clarification or elucidation of facts).

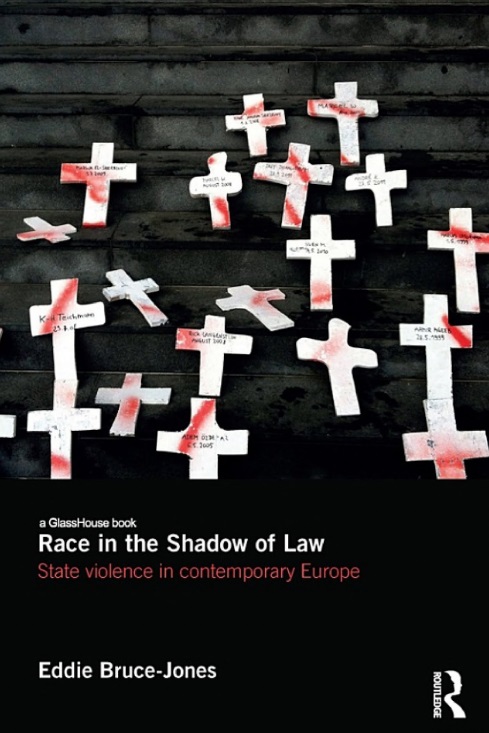

Race in the Shadow of Law examines cases like Jalloh’s in the context of wider issues in Germany at the nexus of anti-Black racism and the law. One of my aims in writing Race in the Shadow of Law has been to tell some of the stories of policing violence and structural racism against black people in Germany, and to tell them to an English-speaking audience. Many anti-racism and anti-police brutality activists in Europe know the names of Mike Brown, Trayvon Martin, perhaps even Rekia Boyd and Aiyana Jones (though, as activists under the banner of #sayhername and at the African-American Policy Forum rightly note, Black women’s stories are generally side-lined in narratives of policing violence). However, few activists outside of Europe may have heard of N’deye Mareame Sarr, Oury Jalloh, Laye Conde, Christy Schwundeck, and Ousman Sey, all Black people who have died in police custody or policing situations in Germany. The stories in the book demonstrate how racism circumscribes the lives of Black people in Germany as in other parts of the world. The Oury Jalloh trial and similar cases reveal that the systemic problems associated with police violence that shape Black lives and Black futures in Europe and the US are continuous, despite their cultural, historical and linguistic cleavages. The differences, in fact, open up possibilities for creative approaches—for drawing on experiences from other contexts and using the differences to interrogate local assumptions about racism, difference and power.

A second aim was to address questions of political and legal change, typically reserved for lawyers and politicians, through approaches taken by organisers, writers and academics. This way of looking at the intersection of race and law helps open up space for both imagining legal avenues and broader discursive and social shifts in efforts to arrive at more just outcomes. Community organizers working on the Jalloh case have been able to mobilize discussions that do not simply follow those posed by the courts, but to reframe them and pose new legal questions, all while focusing on anti-racist analysis beyond the institutions and logics of law.

A third aim in writing this book was to probe some of the ways that racism structures the lives of Black people in Europe. Conceptually, ‘race’ is not an identical construct in Germany as it is in the United States of America, or even within Europe for that matter. To erase linguistic, cultural and other differences will limit our ability to effectively negotiate the phenomenon of racism in context. However, this does not mean that race is conceptually unique to the United States and that race, as a concept, is not valid or applicable in the European sphere. This latter proposition is often a charge of European popular culture—that race is a US obsession, underscored by extreme violence against and mass incarceration of people of color. I aim to critique this proposition, not by mapping racist violence in Europe with US equivalents in terms of quantity or character, but by examining some of the cases that reveal overlaps in quality and format.

A third aim in writing this book was to probe some of the ways that racism structures the lives of Black people in Europe. Conceptually, ‘race’ is not an identical construct in Germany as it is in the United States of America, or even within Europe for that matter. To erase linguistic, cultural and other differences will limit our ability to effectively negotiate the phenomenon of racism in context. However, this does not mean that race is conceptually unique to the United States and that race, as a concept, is not valid or applicable in the European sphere. This latter proposition is often a charge of European popular culture—that race is a US obsession, underscored by extreme violence against and mass incarceration of people of color. I aim to critique this proposition, not by mapping racist violence in Europe with US equivalents in terms of quantity or character, but by examining some of the cases that reveal overlaps in quality and format.

Few academics and anti-racism activists in the English-speaking world know of the significant number of Black people in Germany, and that there has been a cultural, political and literary flourishing among this diverse group over the past three decades. In recent years, it has been particularly important to the Afro-German community to gain international attention on the issue of policing-related violence against people of color. German press coverage of such violence is scant and generally limited to local newspapers and television broadcasts, which drastically limits the prospects that international press, typically concerned with covering national news items, will pick up these stories. Those who protest against the violence and who write about, raise funds for, and litigate on behalf of the dead (such as the Initiative in Remembrance of Oury Jalloh) are the primary reason that these stories have gained at least some traction internationally.

Just last month, in late February 2017, a Working Group for the UN Decade of People of African Descent visited Germany with the aim of better understanding racism in the context of policing. The statement it released was damning:

The Working Group is concerned by the failure to effectively investigate and provide justice in cases of racial discrimination and violence against people of African descent by the state, in particular by the police. One example is the case of Mr. Oury Jalloh, an African asylum seeker, who died in police custody in Dessau in 2005…. The Working Group believes that institutional racism and racist stereotyping by the criminal justice system has led to a failure to effectively investigate and prosecute perpetrators. The Working Group was also informed about other cases: Ousman Sey who died in police custody in 2012 in Dortmund; N’deye [Mareame] Sarr shot by police officers when she went to pick up her child from her white ex-husband; Christy Schwundeck shot by police in a job center in Frankfurt am Main in 2011 and Maria El-Sherbini, a young North African woman was stabbed to death in the high-court in Dresden before her 3-year old son and the judge in June 2009.”

In the book, I discuss the Jalloh case at length, alongside the other cases mentioned in the UN Working Group statement. It has been left largely to activists and advocates to highlight the structural dimension of policing-related deaths, given that there is no central accessible, reliable archive that connects the stories of the dead, or tells them in high resolution. It is difficult to access data on police violence in Germany disaggregated by racial or ethnic background. An overly simple but not infrequent answer to this charge is that race does not function as a social category in Germany the way that it does in, say, the United States. So, the argument follows, race should not be used because reifying such a dubious category does more harm than good. The pressing tension this raises, though, is the plain reality that racial stereotypes still shape the experiences of many non-white and otherwise racialized people in Germany—this is certainly the case for people of African descent.

Critical attention, then, must be paid to how we might recognize patterns of racial discrimination, exclusion and violence. It is difficult to identify and analyze racism without a vocabulary that does the necessary work of lifting racism’s structural and institutional dimensions out of obscurity. Given other cases of state violence that have emerged in the last few years (including the now infamous National Socialist Underground case, which addresses the extent to which German secret service and police knew about the murders and attacks of Turkish and Turkish-German people, planned and executed by a neo-Nazi terror cell), a broad discussion of structural racism and state violence is most urgent.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.