The Missing Link: Conservative Abolitionists, Slavery, and Yale

We’re living in one of those moments that doesn’t happen often: elite universities are suddenly interested in their slave-related pasts. Or at least they’re pretending to be—heaven knows the public relations disaster they’d find themselves in if they ignored student-driven demands for a public reckoning. Whatever the motivations, the trend is unmistakable. Earlier this month, Harvard held a high-profile conference on the university’s links to slavery. In February, Columbia unveiled a website detailing the school’s ties to slavery, at roughly the same time that Yale agreed to remove the name of John C. Calhoun, of slavery as “positive good” fame, from one its residential colleges. Georgetown’s efforts have been most impressive: in the fall, they announced the creation of a center for the study of slavery and that they would offer admissions’ preference to the descendants of the 272 slaves the university owned and sold to finance its debt. These efforts of course build off earlier work, from Brown University president Ruth J. Simmons’ pioneering effort in 2003 to get her university to investigate its ties to slavery, to Craig Steven Wilder’s remarkable recent history, Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities.

Despite the importance of all this work, I worry that the focus on slaveholders and slave traders misses an important link tying universities to slavery: antislavery supporters, particularly northern white advocates of colonization, or the idea that former slaves should be voluntarily resettled once free. For decades, historians dismissed colonizationists as slavery’s apologists. But increasingly, scholars are beginning to understand them, or at least colonization’s northern white supporters, as what I call conservative abolitionists. Radical black and white abolitionists famously denounced the colonization movement in the 1820s and 1830s, giving rise to the much-studied Garrisonian movement. But to see radical abolitionism as the only authentic antislavery position is to miss a critical point: what made the radical movement radical was not so much that it wanted to end slavery, but, at least in part, that it envisioned blacks living alongside whites in a slave-free republic. By contrast, northern colonizationists accepted emancipation but rejected integration. It was not a fringe position. William Lloyd himself started out as a colonizationist, and among northern intellectuals, colonization remained far more respectable than radical abolitionism until the Civil War. Lincoln even toyed with the idea until emancipation.1

Benjamin Silliman, appointed Yale’s first chemistry professor in 1802 and a prominent northern colonizationist, provides a perfect case study, demonstrating the way conservative abolitionists secured elite universities’ ties to slavery. Silliman played a central role building up Yale’s scientific institutions, from expanding its science curriculum, to helping found its medical school and natural history museum. And many of the Yale alumni he relied upon for financial support were prominent slaveholders, including John C. Calhoun. Studying Silliman’s letters, memoirs, and Yale’s treasury records not only shows how conservative abolitionists tied slaveholders to Yale’s financial fortunes: it also reveals how slave money helped build up Yale’s science programs in particular. If scholars are to continue researching slavery’s ties to universities, which they must, they need to pay closer attention not only to which universities profited from slavery, but what particular branches of knowledge within those universities gained from it.

Born in 1779, Silliman grew up in the heyday of gradual abolitionism. Like many of his scientific heroes, he believed slavery should end gradually, first by ending the slave trade, then by encouraging states to enact gradual emancipation laws. But like many of the early white abolitionist elite, he was ambivalent, if not outright opposed, to free blacks’ equal place within the nation: “It is obviously wrong to urge, much more to coerce, them to leave it,” Silliman said in defense of voluntary colonization, in 1832. Better to “convince them [African Americans] that it is for their interest and happiness, and they will [look] forward to emigrate.”

Silliman’s antislavery conservativism was in part shaped by his reliance on slaveholders to fund Yale’s scientific program. As Yale’s first chemistry professor, Silliman made it his mission to establish the school as a leading institution for science education. Central to that effort was his effort to acquire what was called the Gibbs Cabinet. A collection of nearly 10,000 exotic minerals, the cabinet formed the basis of what is today’s Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, and quickly became a major marketing tool for the university. “This cabinet doubtless exerted its influence upon the public mind in attracting students to the College,” Silliman wrote in his journal.

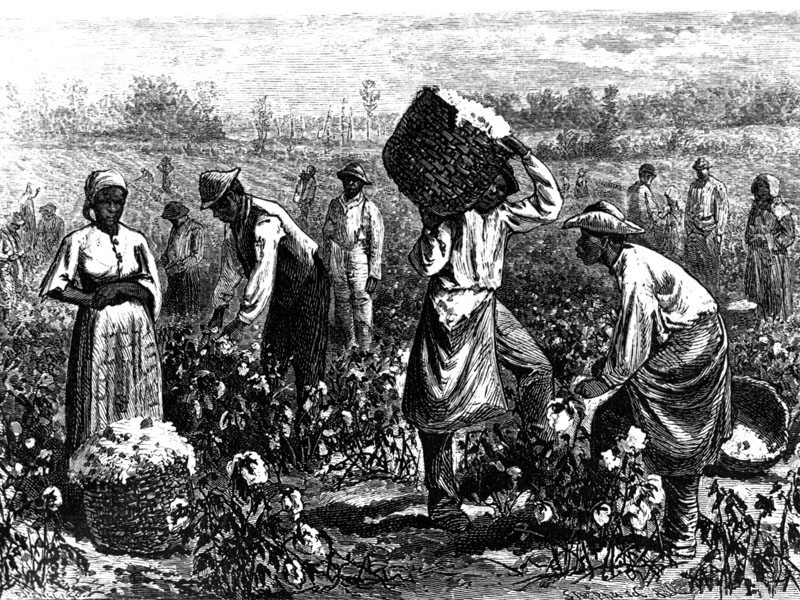

Slavery’s presence hovered over the entire collection. Many of the minerals came from deep within slave country: Louisiana, Maryland, and “good size pieces from Georgia, Tennessee and Virginia.”2 Silliman added minerals to the collection himself, occasionally travelling in “a private carriage with a servant”—most likely a euphemism for slave—to collect minerals, and noting in his journal, in 1836, how slaves “were employed to crush the quartz for us in heavy iron mortars.”3 The cabinet’s namesake, George Gibbs, came from a prominent slave trading Rhode Island family; Gibbs also owned slaves well into the nineteenth century. Silliman was waited upon by “an intelligent coloured servant”—a slave—named “Scipio” during his first visits to see the collection in Newport; Gibbs’ account book reveals that, as late as 1815, he owned at least five other enslaved men and women—Hannibal, Joseph, Betsey, Peter and Mary—on his Long Island estate.

To purchase the cabinet, Silliman relied extensively on slaveholding alumni. South Carolina alumni trailed behind only Connecticut and New York, making it the third largest donor class. And among South Carolina’s most generous donors was none other than John C. Calhoun. He donated $100 for the cabinet in 1825. Calhoun’s relationship with Silliman went deep. He developed a love for science after taking one of Silliman’s first chemistry classes, and Silliman keenly cultivated the relationship as Calhoun’s political career took off. In 1818, Silliman sent Calhoun, the newly appointed Secretary of War, a copy of the new journal Silliman established, the American Journal of Science, which soon became the nation’s premier scientific journal. “The utility of such a work, particularly in this county, must be apparent,” Calhoun wrote to Silliman upon receiving his copy. Four years later, Calhoun commissioned Silliman to report on the state of “the sciences” being taught at West Point.4

Calhoun and the Gibbs cabinet were hardly the only ties linking Silliman to slavery. Silliman worked tirelessly to attain profits from the cotton gin for Eli Whitney (Yale, class of 1792) and his descendants. In Silliman’s 1832 eulogy to Whitney, published in the American Journal of Science, he lavished praise on the cotton gin, comparing Whitney’s genius to that of Milton, Shakespeare and Cicero. Not a word was mentioned about the cotton gin’s direct role in fueling slavery’s astronomical growth.

Around the same time, Silliman won a prestigious federal commission to investigate the nation’s sugar-making industry. Silliman tapped several Yale chemistry professors to help him investigate southern sugar plantations, and received funds from the university’s president to help defray the costs of their southern sojourns. 5 Silliman knew what he was getting himself into: he told a professor he sent down south to quietly take note of how slaves were being treated: “The slaves on the sugar estates—do they appear hard worked, dispirited, and oppressed? 6 Then, in parentheses: “(Open your eyes and ears to every fact connected with the actual condition of salary everywhere-but do not talk about it–hear and [see] everything but say little.” But, as with his Whitney eulogy, he made no mention of slaves in the final report he delivered to Washington, D.C. in 1833.

Silliman’s reliance on slaveholders to establish Yale’s scientific reputation helps explain why he endorsed the most conservative agenda within the broad antislavery platform: colonization. Colonization, rather than radical abolitionism, offered him the only legitimate antislavery position his slaveholding patrons would tolerate. Nor was Silliman alone. Many university professors in the North continued to embrace colonization well after most African American women and men rejected it. We ought to pay close attention to these northern colonizationists. Their antislavery agenda, not the radical one, was considerably more popular among white antislavery elites before the Civil War. To see them as genuine abolitionists—albeit representatives of a conservative abolitionism premised on white supremacy—is to see how the fortunes of our nation’s universities depended not only on slaveholders, but on their strange and sometime allies, conservative abolitionists.

- William Lloyd Garrison started out (in the 1820s) endorsing the American Colonization Society’s colonization schemes, though he never joined a branch of the ACS itself. See W. Caleb McDaniel’s The Problem of Democracy in the Age of Slavery: Garrisonian Abolitionists and Transatlantic Reform (LSU Press, 2013), 37. ↩

- Ebenezer Baldwin, Annals of Yale College, 2nd Edition (New Haven, 1838), 252. ↩

- Benjamin Silliman, “Origin and progress of Chemistry,” Mss. Silliman Family Papers (SFP), Yale University Library, Series III, Reel 1, Book 6, p.199 (mf). ↩

- John C. Calhoun to Silliman, May 13, 1822, Mss. SFP, General Correspondence,” Series II, Reel 10 (mf). ↩

- Jeremiah Day to Charles Shepard, Nov. 16, 1832, Mss. Shepard Papers, Amherst College Archives, Series 2, Box 3, Folder 5. ↩

- Sillman to Charles Upham Shepard, “Memoranda,” Nov. 7, 1832, Mss. Shephard Papers, Series 2, Box 3, Folder 5. ↩