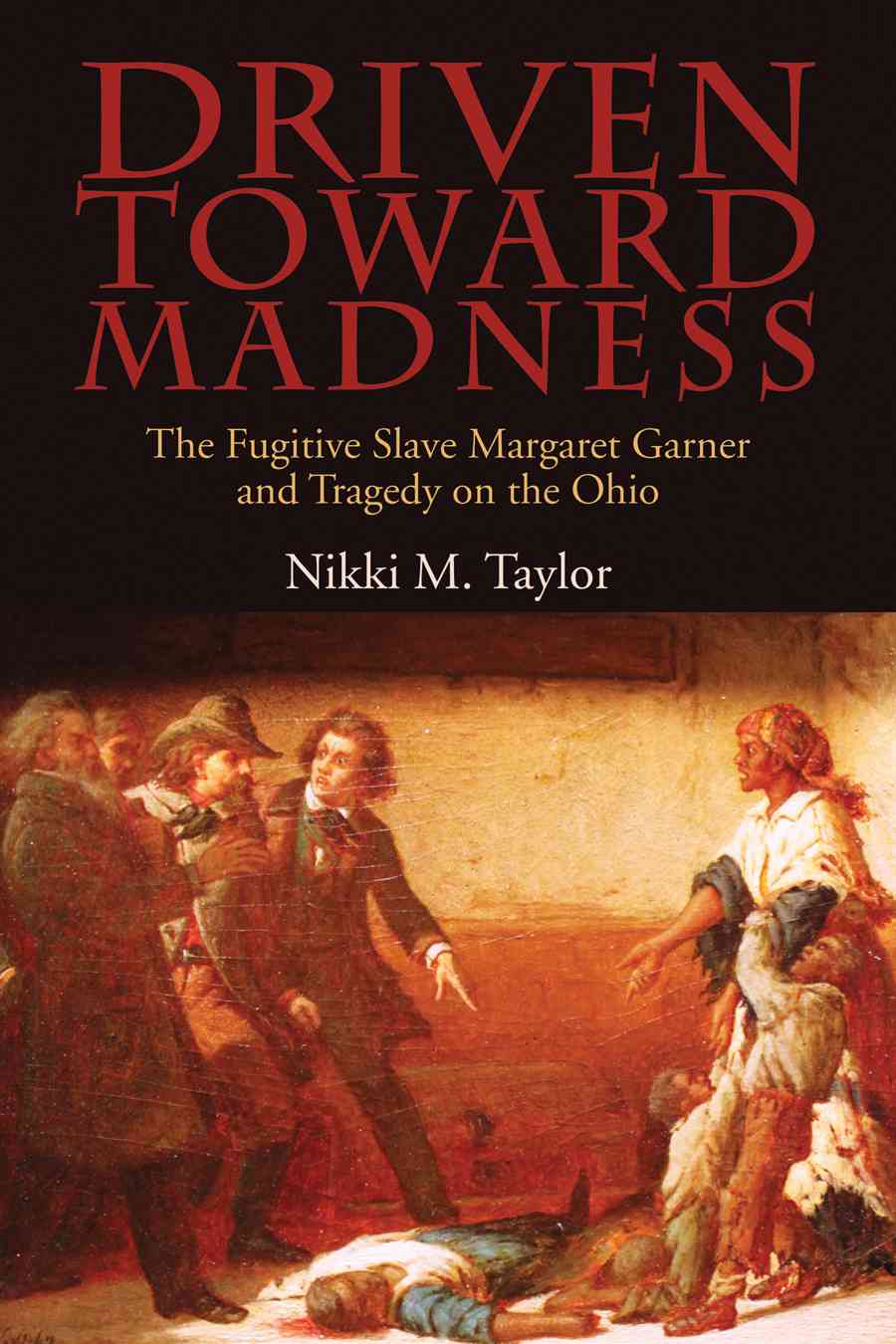

The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio

This is an excerpt from the fourth chapter of Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio by Nikki M. Taylor. Margaret Garner was the runaway slave who, when confronted with capture just outside of Cincinnati, slit the throat of her toddler daughter rather than have her face a life in slavery. Her story inspired Toni Morrison’s Beloved. In Driven Toward Madness, Taylor brilliantly captures her circumstances and her transformation from a murdering mother to an icon of tragedy and resistance. This excerpt grapples with whether or not Margaret Garner had been sexually assaulted by her owner Archibald K. Gaines and explores the possibility that he—not her husband, Robert–had fathered her daughters, Mary and Cilla. The question initially had been raised by Women’s Rights advocate Lucy Stone who insisted that the light complexions of the Garner daughters proved Archibald was their father. This excerpt places Margaret Garner in a historical context that rendered black women unrapeable in the eyes of the law. It reveals how race, gender, status, and powerlessness made Garner particularly vulnerable to Gaines and other white slaveholding men. This excerpt has been reprinted with the permission of Ohio University Press.

Allegations about Gaines’s sexual exploitation of Margaret were first raised by Lucy Stone during the fugitive slave hearing. In open court, she gave a speech that laid bare the most controversial core of the entire tragedy—rape and race mixing—when she declared, “The faded faces of the negro children tell too plainly to what degradation female slaves submit. Rather than give her little daughter to that life, she killed it.” Stone bluntly stated—as none but a women’s rights advocate would dare—that the Garner children’s light complexions, or “faded faces,” testified to Margaret’s “degradation”—which in the nineteenth century, was a euphemism for sexual abuse. In one declaration, Stone not only had accused Gaines of sexual abuse and insinuated his paternity of Margaret’s children, but also explained that the hell Margaret tried to save her daughters from was sexual abuse. In short, Stone insisted that Mary’s murder had been a gendered mercy killing, of sorts.

Had Margaret Garner really told Stone that she had been raped by Gaines and that he fathered her daughters, as Stone implied? Perhaps; perhaps not. Garner may have felt comfortable enough with Stone to confess these salacious secrets. After all, Stone had an empathetic ear: not only was she a women’s rights advocate and abolitionist, but she fully empathized with Garner’s decision to kill her daughter. But Stone’s accusations complicate this history and lead to at least two plausible theories of what happened to Garner.

The question of whether Margaret Garner had a sexual relationship with Archibald K. Gaines, and if it constituted rape, cannot be known with absolute certainty. The answer cannot be disentangled from nineteenth-century gender and racial assumptions; nor can it be disentangled from how social and economic power—and powerlessness—functioned in nineteenth-century society. At one end of the power spectrum were powerful white men, who wielded unchecked racial, gender, and economic power in southern society—power that was protected and magnified by the legal system.

At the other end of the spectrum, enslaved people were powerless and considered chattel—property that could be bought and sold in the marketplace. African American women, in particular, were treated as “purchasable sexual and economic commodities.” When a man purchased a bondswoman, he also purchased the right to have sex with her. The business transaction that completed her sale is all that it took to open the door to unlimited and unchecked sexual access to her. In antebellum slave society, ownership, power, and sexual access were inextricably linked as it related to owners. Gaines owned Garner’s body: it was his to do with what he wanted, regardless of her will or desires. And no one could stop him—not even the law.

In the nineteenth century, the legal (but heteronormative and raced) definition of rape was “carnal knowledge of a woman forcibly and against her will.” In order to convict an alleged rapist, officials needed to prove that the sexual intercourse occurred by force, or with some violence, and against the woman’s will. Everything about slavery was maintained by violence and done against enslaved people’s wills; sex was no exception.

Slaveholders owned the bodies, and ordered the movements of their bondspeople. The intertwined elements of ownership, abuse, and power, meant that sex with those with stark powerlessness—like enslaved women—sometimes made physical force unnecessary. Owners used coercive tactics to obtain sex and sexual favors from them in a myriad of ways, including threats of violence. In fact, the threat of violence was second to violence as a form of sexual coercion. Violence was so pervasive that the threat of violence often is all it took to get these women to submit to sex.

Slave owners controlled the provisions, punishments, workload, quality of life, and stability of slaves’ families, so they could deny or threaten any aspect of their lives to get a woman to submit sexually. Sometimes, too, promises of rewards and leniency were used for the same ends. For example, an owner could demand sex in exchange for visitation rights to loved ones, for better food, or time off. In short, enslaved women had no real choices about whether they would or would not engage in sex with their owners. Because of this lack of real choices, all sex between an unfree woman and her owner can be considered nonconsensual.

Kentucky, though, did not make force, violence, or the woman’s consent the standard to define rape; race was the first standard. Kentucky law defined rape as to “unlawfully and carnally know any white [emphasis added] woman, against her will or consent.” In other words, only white women could be victims of rape in the eyes of the law; only men who raped them were rapists. This standard meant that even if Garner had gone to officials complaining of sexual abuse, the existing structure of the law did not allow her rapist to be arrested or convicted. Certainly, one cannot ignore the legal and social realities of the world in which she lived.

As an enslaved person, an African American, and a woman, Margaret Garner belonged to three groups of disempowered people. The intersection of patriarchy, white supremacy, and wealth meant that as a white male slave owner, Gaines had all the power. The intersection of race, gender, and enslaved status meant that Margaret’s powerlessness had a multiplicative effect on her oppression. Consequently, she was vulnerable to sexual assault at the hands of her owner and any other white man, for that matter. In nineteenth-century America, there were statutes against raping white women—some even raised the death penalty for such an offense, but none specifically prohibited the rape of African American women.

Slaveholders and other elite men easily avoided both prosecution and conviction. What this also tells us is that a slave owner’s social and economic power to sexually abuse enslaved women with impunity made sexual abuse a privilege granted through slavery, ownership, socioeconomic status, and even whiteness.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

As someone who admires Nikki Taylor’s work, I have been looking forward to reading her latest book. I’m a bit behind, but there’s just been so much new terrific scholarship in the field. I’m particularly interested in reading what will undoubtedly be some really sharp analysis by Taylor on the law and the psychology of slavery, especially after reading Sowande’s Mustakeem’s Slavery At Sea.

This work sounds tremendous and demonstrates that what we term intersectional now is something that has been lived by black and Indian women in US since onset of this place as colony…

I wish I had seen this before I submitted my book order for the fall. The idea the black women were and still are unrapable is difficult for my students to process.

The mindset is still here today. RIP Sandra Bland and the rest. smh Much respect Margaret Garner.

This was a great write up. I try to learn these things on my own. Twitter gives me the opportunity to reach you, so I read and learn. This was a very sad story in how these disparities exist today. These white men raped our women without any consequences, but the privileged white woman had the protection of the law. Even when it came to the extremity of the death penalty if they were raped. It sounds horrible about Margaret Garner slicing the throat of her daughter, by I couldn’t have imagined what was going on then. I knew she didn’t want her daughter to go through what she had to go through.

Thank you for sharing a portion of the book, it is very exciting work! As a graduate student I’m very curious to learn about the archives Dr. Taylor consulted and the notion of madness she engages in the title. If there’s any indication from the excerpt, I expect an excellent discussion of historical context with respect to local laws, medical practices, and even an enthographic or anthropological study of the psychological and emotional conditions and experiences of enslaved people, especially women. Margaret Garner’s story is an important one to tell because of contemporary trends in popular discourse that erase the culture of abuse and negligence at the heart of American chattel slavey and the laws that codified white supremacy. Moreover there are too few studies of enslaved women’s actions regarding reproductive health and motherhood. People today have forgotten than Black women are deemed poor mothers because of historical associations to abortion and infanticide that erase the context of slavery, poverty and racism while spectacularizing the supposed depravity of such acts. We as Black women scholars work as Dr. Taylor does to introduce how compassion and love could be embedded in such a choice.

This book is going to be a compelling addition to classrooms (not to mention book clubs). With Lucy Stone’s testimony, we see vividly that this is not a presentist speculation but a live and urgent question for 19th century America. Through Nikki Taylor’s historical work, the discussions will tumble forth: consent and the law, institutionalized violence, and the excruciating complexity of enslaved motherhood in a time of the maternal law of descent. Looking forward to assigning this.

Thank you for this important study! I look forward to reading more.

This is a tantalising chapter. Garner’s “gendered mercy killing” demonstrates the enslaved Black women’s awareness of her positionality as “unrapeable” chattel. It was a powerful rejoinder against the idea that Black women were powerless objects who could do nothing to confront the “red stain of bastardy” that stemmed from her “degradation.” Resistance to the machinery of white supremacy is articulated in many ways. Margaret made a choice. To her, a bodily death was a better option than her child facing “unlimited and unchecked sexual” abuse. In Stone, we see a complicated ally laying bare the inhumanity of it all. I don’t see the madness in Garner’s actions. I see agency and resistance to a sick racial state that rendered its multilayered racial violence against Black women as permissible and invisible. I see Garner and Stone—albeit in different ways, challenging a poisoned system to see its own madness. I can’t wait to read more!