Booker T. Washington and the White Fear of Black Charisma

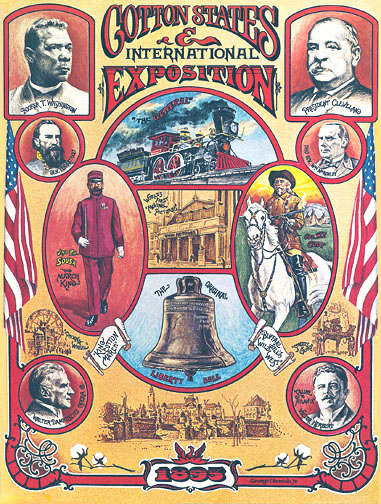

First, the crowd gathered at the Atlanta Exposition on September 18, 1895, heard the band play “Dixie”; then they listened to Booker T. Washington speak. The audience was mostly made up of Southern whites, and they cheered for “Dixie,” but they cheered for Washington, too. “Within ten minutes,” wrote New York World reporter James Creelman, “the multitude was in an uproar of enthusiasm. … It was as if the orator had bewitched them. … The whole audience was on its feet in a delirium of applause.” Creelman, like many white listeners, found Washington’s performance electrifying. “A Negro Moses,” he concluded, “stood before a great audience of white people and delivered an oration that marks a new epoch in the history of the South.”

What makes Washington’s Atlanta triumph so remarkable, even today, is that it flies in the face of something we know to be true: throughout American history, many whites have feared black charisma. Though some have of course felt threatened by any African American in a position of leadership, the charismatic black orator appealing to audience emotions has represented, to many white imaginations, a uniquely terrifying figure. This fear is not without foundation; rather, it is a testament to charisma’s destabilizing power. Throughout American history, whites who oppose racial equality have feared black charismatic leaders because black charisma has proved itself a mortal threat to white supremacy.

“Charisma,” wrote the German sociologist Max Weber a hundred years ago, “is indeed the specifically creative revolutionary force of history.” Among African Americans, charisma represented a prophetic tradition of oratory that grew out of the religious awakenings of the early nineteenth century. “The Preacher,” wrote W. E. B. Du Bois in 1903, “is the most unique personality developed by the Negro on American soil.” Du Bois noted “the stamping, shrieking, and shouting, the rushing to and fro and wild waving of arms, the weeping and laughing, the vision and the trance” that were omnipresent in sermons by black ministers. “A leader, a politician, an orator, a ‘boss,’ an intriguer, an idealist,” continued Du Bois – “all these he is, and ever, too, the centre of a group of men, now twenty, now a thousand in number.” Du Bois’s depiction of the charismatic preacher as male was no accident, for black charisma was from the beginning usually gendered masculine, both by white observers and by the male-dominated black leadership class itself.

Notwithstanding its religious roots, black charismatic oratory was fundamentally political in two ways. First, the mere act of inspiring a crowd endowed charismatic African Americans with an authority that challenged the prevailing racial hierarchy. Second, charismatic black speakers hoped, through the content of their speeches, to open the eyes of white listeners to their role in maintaining racial oppression. “Cultivate the oratorical,” African American college professor William G. Allen urged listeners in 1852, “do it diligently, and with purpose; remembering that it is by the exercise of this weapon, perhaps more than any other, that America is to be made a free land, not in name only, but in deed and in truth.” Charisma, many African Americans realized, was a source of political power; deployed effectively in service of racial equality, it could strike at the heart of the American racial order.

In practice, however, black leaders who appealed to white audiences for better treatment faced ferocious opposition. The white audience cheering for “Dixie” at the Atlanta Exposition almost always stood between them and the equality they sought. Many whites, black orators found, were both well aware of black charisma’s political potential and violently opposed to the racial equality it promoted. So why did an audience of white segregationists hail Booker T. Washington as a “Negro Moses” and listen, enraptured, to his charismatic speech on race relations?

That Washington gained the ear rather than the ire of the whites who cheered for “Dixie” was due, of course, to his ideology. Washington’s speech at the Atlanta Exposition was a masterful blend of compromise, cowardice, and accommodation. “The wisest among my race,” he insisted, “understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly.” Instead, Washington proposed that African Americans should withdraw their demands for every type of equality in exchange for the opportunity to become skilled laborers. To win the cooperation of whites, Washington was willing to abandon virtually everything African Americans had sought for generations. Accordingly, Washington won white approval in a way no other black charismatic leader could match, but his presence on the national stage served largely to bolster the Jim Crow system and undermine the cause of black equality.

Unlike Washington, black charismatic orators throughout history who have advocated for racial equality have found most white audiences hardened, closed-minded, and determined to silence them by force. Whites deported Marcus Garvey, silenced Fannie Lou Hamer, assassinated Martin Luther King, Jr., vilified Malcolm X, marginalized Jesse Jackson, delegitimized Barack Obama, and, just in the last few months, conducted a racially-motivated smear campaign against Keith Ellison. One by one, these African American leaders learned Washington’s lesson the hard way: white acceptance of black charisma was possible only when blacks refrained from openly challenging the racism of their white audiences. White Northerners supported King’s quest for equality when his foils were Southern sheriffs, but when King began criticizing Northern racial attitudes his white supporters turned against him. Similarly, “Obama’s embrace of white innocence,” Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote recently, “was demonstrably necessary as a matter of political survival. Whenever he attempted to buck this directive, he was disciplined” by irate white audiences.

In a recent essay on the Obama presidency, Tressie McMillan Cottom offered an explanation for the white fear of black charisma. “Those of us who know our whites,” she wrote, “know one thing above all else: whiteness defends itself. Against change, against progress, against hope, against black dignity, against black lives, against reason, against truth, against facts, against native claims, against its own laws and customs.” Indeed, the history of white responses to charismatic black appeals reflects above all a panicked sense of self-preservation – a recognition that, in some nebulous way, every well-spoken black leader represents a dangerous challenge to white dominance.

The white fear of black charisma, then, is itself the best evidence of charisma’s power to disrupt oppressive systems of power. Whiteness defends itself, but only against legitimate threats. Whites would not have been so quick to condemn Garvey or Hamer or Malcolm or Jackson had they not recognized those leaders’ revolutionary ability to advance equality; they would not have been so eager to embrace Washington had they not viewed him as a bulwark against effective black activism. The narrative of black charisma is a long history of victimization, but it is also a story of simmering potential.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

But is it charisma, or demagoguery, or charisma with leadership and a unifying vision? My late ex-stepfather had charisma — but that alone didn’t make him a leader or a dangerous demagogue to Whiteness or to anti-racist Black activism. Also, as Eddie S. Glaude and Ibram Kendi have made clear in their recent books, Obama walked a tightrope that upheld color-blind racism through racial tropes of respectability politics and Black violence while occasionally being critical on American racism in general. The jealously factor aside, the danger for many Whites wasn’t Obama’s oratory or charisma. It was his very presence in the most powerful position in the world, one reserved for White males (most of this applies to Jesse Jackson post-1984 as well).

Great comments. I agree completely with Glaude and Kendi (and Cottom, and Coates) on Obama and respectability politics. That said, I think we have to acknowledge a difference between the white reception of Obama, who was hated by many whites but beloved by many other whites, and white attitudes toward figures such as Garvey or Malcolm, which were almost universally poor. For some whites, the simple act of Obama being president was threatening enough, but for others, it was mitigated by his embrace of respectability politics.

Generally speaking, I think black charisma is one of the characteristics of black leadership that whites often find threatening. When combined with demands for racial equality or rhetoric that challenges white supremacy, when combined with the mere fact of black leaders occupying new and more prominent roles, it simply compounds and enhances already-existing white fears. I think many whites still see in black charisma what they saw in Southern black ministers in the 1830s: a Nat Turner around every corner. Leadership and rhetoric contribute to that fear, but charisma does, too.

“Those of us who know our whites?” What staggering bigotry!

Hello-

There is important work in black feminism on charisma, including a major recent text: Charisma and the Fictions of Black Leadership by Erica Edwards and classic works such as Race Men by Hazel Carby that it would be important to engage as well as numerous works in black women’s history. I think this analysis would be essential for thinking about the political perils of charismatic male leadership.

Great point, and I love Erica Edwards’ book in particular (I cited it in my own book on which this post is based). As Carby points out, white men and black men have worked together to enshrine the idea of the masculine “race leader” going back to Frederick Douglass’ time (Leon Fink has a good essay on this as well, in Progressive Intellectuals and the Dilemmas of Democratic Commitment). White men in particular seem to have had conflicting priorities here: building up charismatic black men as race leaders, then attacking them as dangerous unless they disclaimed any interest in racial equality. African American women such as Maria Stewart complicated this narrative in ways that challenged both white and black patriarchal formations.