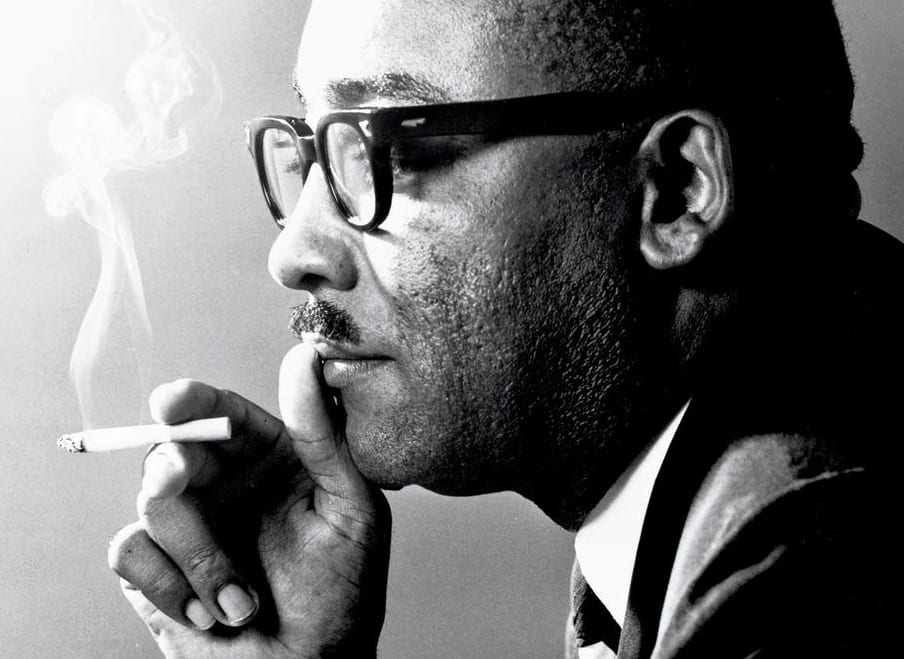

On the Life and Legacy of Black Journalist Louis Lomax

We still have far too few histories of Black journalists. Even as biographers have written on Alex Haley, Ethel Payne, Louis Austin, Emory O. Jackson, and Lerone Bennett in the last decade, many other Black reporters and editors still deserve their own studies.

Thomas Aiello’s new work, The Life & Times of Louis Lomax: the Art of Deliberate Disunity, is the newest addition to this literature. A historian at Valdosta State University, Aiello is an impressively productive writer, the author of no fewer than twelve books in the last thirteen years. This is his second work on Black journalists, his first being a history of the Atlanta World network.

In the decades following World War II, Louis Lomax was one of the leading commentators on Black life in the United States, the author of five books and countless stories, and the host of his own syndicated television talk show. By the time he died in 1970, Lomax was a nationally recognized expert on Black politics. Presidential candidates called on him for endorsements and universities hired him to teach.

At times, Lomax’s work was marked more by provocation than principle, more by sensationalism than substance. Proximity to fame and the pursuit of the next advance were constant motivators, especially when he faced money issues.

The pursuit of career accomplishments, more than any particular ideology, seems to have grounded Lomax’s life. It would be an understatement to describe Lomax’s views as flexible. His stances on politics depended more on who he was in the room with—and who he might immediately disagree with. Indeed, Aiello’s subtitle, The Art of Deliberate Disunity, refers to an August 1963 speech from Lomax days before the March on Washington where he lambasted “Negro euphoria, that seizure of silly happiness and emotional release that comes in the wake of a partial civil rights victory” (1). If anything, Lomax made a name for himself as a contrarian, someone who chastised nationally prominent civil rights organizations for being too cautious while criticizing more radical Black groups for being reckless.

Nowhere were Lomax’s ideological contradictions more evident than in his relationship with the Nation of Islam. Lomax’s work with Mike Wallace on The Hate That Hate Produced, a CBS television documentary on the NOI, catapulted him to national prominence in 1959. Nothing less than a hatchet job, the breathless exposé made Lomax a known name to journalists across the country. Yet even as it smeared the NOI as something akin to a Black supremacist terrorist organization, it also gained it thousands of new recruits. Lomax may have helped a white journalist condemn the NOI on national television, but the documentary’s positive impact on the group’s membership rolls kept him in the good graces of both Muhammad and Malcolm X.

This was Lomax’s dual legacy—he helped a white news host and white-owned network smear the NOI, but in the process he made his career, dramatically boosted Elijah Muhammad’s profile, and forged a lifelong friendship with Malcolm. Ironically, Aiello points out, Lomax agreed with much of the NOI’s diagnosis of America’s racism, even while he took issue with its advocacy of separatism and Black supremacy.

As Lomax became a leading commentator on Black politics, he attracted his share of critics among the African American left. More than a few Black writers chafed at Lomax’s eagerness to assume the role of gatekeeper for whites seeking entrée into discussions on race and civil rights.

Lomax, meanwhile, was ecumenical in the range of Black political leaders he engaged. He had frequent conversations with everyone from the NOI to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He seemed to hold the NAACP in particular disdain, repeatedly making it Exhibit A in his arguments on the ineffectiveness of overly cautious Black organizations, but he also collaborated with the group at times. Harder to understand was Lomax’s willingness to accommodate members of the racist John Birch Society on his television show and especially the personal friendships he had with Birch leaders like John Rousselot.

Aiello has produced a nuanced and considered biography of a very complex man, an important book on a major figure in postwar Black life who’s badly needed a biography for decades. The work is well researched, the first to draw on Lomax’s papers, which are housed at the University of Nevada, Reno (yet another mystery about Lomax that has no easy explanation). Aiello is to be commended for his dogged pursuit of the real Lomax, a man who habitually lied about his own biography and embellished his resumé. He isn’t an easy man to chronicle.

One area that deserves closer scrutiny, however, is Lomax’s reporting on the uprisings of the late ‘60s. Two incidents stand out as especially questionable. In an August 1967 Detroit News article published shortly after that city’s uprising, Lomax denounced Jim and Grace Boggs, Albert Cleage, bookseller Ed Vaughn, and Milton and Richard Henry as the “strangest Black Power amalgam in America,” essentially implying the activists assisted in attacks on police officers in Detroit. Carefully relying on innuendo without making explicit accusations of criminal activity, Lomax insisted that the Boggses “disappeared during the uprising,” which he maintained “raises doubts and suspicions that will prevent the achievement of any kind of Negro unity for a long time to come.”

Aiello briefly discusses the article but passes on analyzing the motives behind it. Was this just the same Lomax who defaulted to sensationalism to sell more copy? Or did Lomax have a more personal reason for placing blame on the uprising at the activists’ feet? Similar questions arise from a 1968 article in the Boston Globe following Martin Luther King’s assassination. The article opened with a dramatic claim: “While White America weighs the fine points of the federal riot report, Black America is busy stockpiling weapons. Not merely bullets and rifles. But bazookas, machine guns, and grenades.”

It’s an astonishing assertion and, like many in the Detroit story, one based entirely on unnamed sources. In neither case does Lomax offer any explanation of how he knows these things. Lomax was open to pursuing conspiracy theories, as Aiello explains in his final chapter outlining the journalist’s investigations of both Malcolm X and King’s murders. But what explains his confidence that activists were intent on armed warfare? Especially in the Detroit News piece, it’s worth considering whether Lomax’s “reporting” may have been planted by law enforcement, a practice of the era that is well documented. Lomax, as Aiello tells us, was not afraid to talk to the FBI. In fact, on at least one occasion he sought out the Bureau to volunteer information he believed identified associates of George Wallace as responsible for King’s murder.

Aiello’s account ends with an open question: how did Lomax die in 1970, at the young age of forty-seven? The official reports state that he was killed in an automobile accident due to driver error. But his wife never accepted that explanation, nor did her lawyers. Some have even suggested that Lomax was sabotaged in order to halt his inquiries into Malcolm and King’s deaths. Aiello wisely avoids speculating about the accident’s cause but is right to tell us that the official account is less than satisfying.

In the final analysis, Lomax defied easy explanation. Perhaps the best interpretation that Aiello offers us came from Bill Lane of the Los Angeles Sentinel, writing in 1967. Lomax was “always being called a ‘sellout to the Negro,’ ‘anti-Jewish,’ a ‘snob who refused to live among the people he claims to represent,” Lane remarked. But maybe Lomax really wasn’t as fixated on attacking others as he was on advancing himself. “Truth is, Louis Lomax represents one entity—Louis Lomax” (148).

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.