Malcolm X and Anti-Imperialist Thought

This post is part of our online forum, “Remembering Malcolm,” edited by Garrett Felber.

“No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.”— Albert Einstein

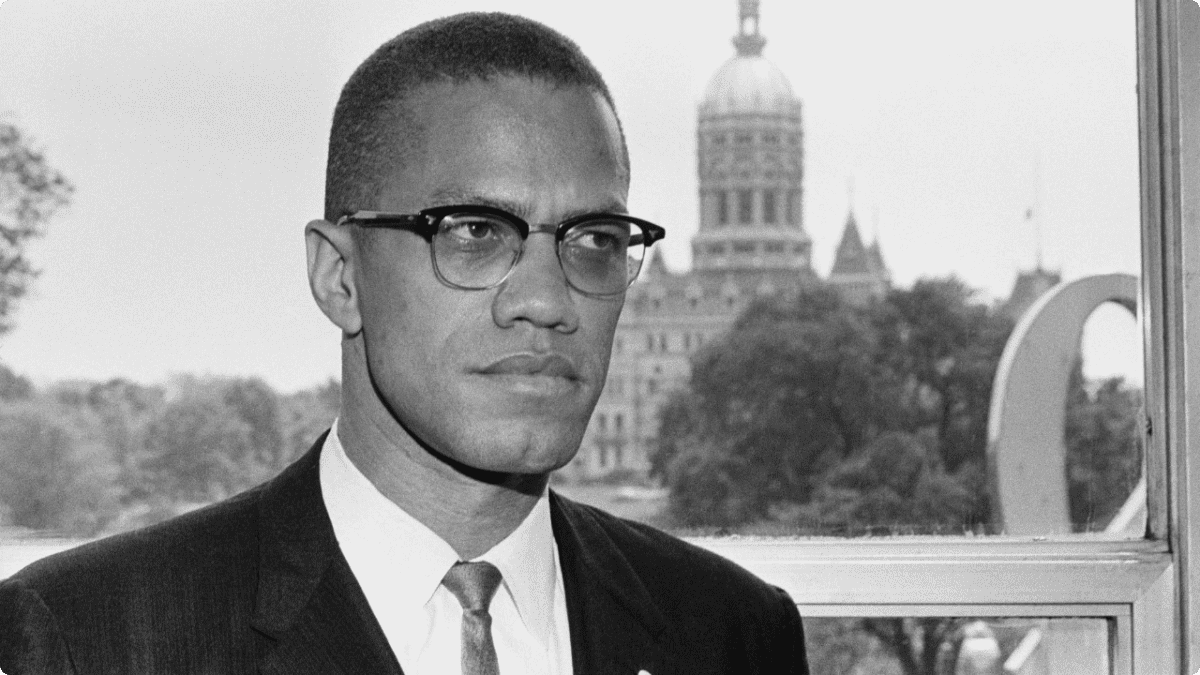

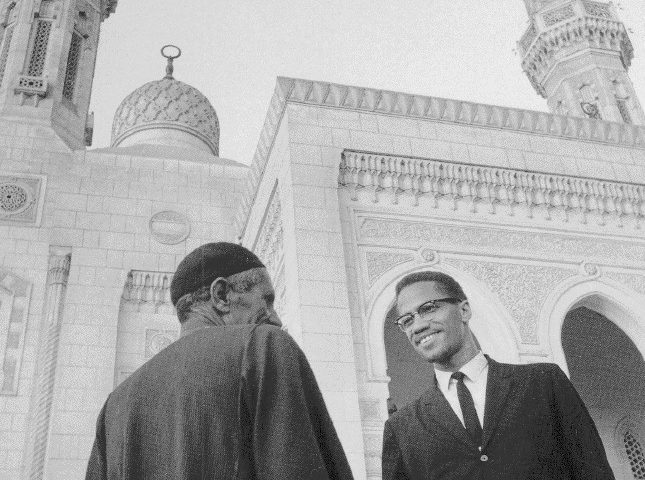

By the spring of 1964 Malcolm X was undergoing a profound intellectual metamorphosis. Having extricated himself from the narrow black nationalism of the Nation of Islam, he was straining toward a more expansive—and radical—internationalism. Travel and exposure to a range of revolutionary figures and experiences helped enable the awakening. Yet the political leader’s epiphanies also reflected his own principled commitment to reappraisal. As he often acknowledged near the end of his life, he was engaged in a strenuous effort to “broaden my own scope.”

Political growth deepened Malcolm’s anti-imperialism. The African-American militant had long been an unsparing opponent of U.S. empire. His condemnation of America’s role abroad grew more incisive as he shed old dogmas. He devoted much of his oratory to skewering the hypocrisy of the nation that had proclaimed itself “the leader of the free world.” His critiques were designed to rouse black Americans and their prospective overseas allies, wresting them from the fog of Cold War thought and compelling them to see the world as it was. Once they had grasped the realities of U.S. hegemony, he believed, they could devise lucid programs of self-liberation in concert with revolutionary forces across the globe.

Cultivating such awareness would not be easy. Most Americans in the mid 1960s remained mired in Cold War logic. Though they had launched a mass insurgency against structural racism, African Americans were no exception. Anticommunism and white supremacy crippled black consciousness while limiting the pace and nature of social change. Recognizing the constraints of orthodox thought, Malcolm sought a wholesale rupture. He would help sever the shackles of American nationalism, guiding black folks off the Cold War “plantation” and fostering a more critical worldview.

This was not simply a political crusade. In Malcolm’s view, a total psychological reconstruction was necessary. African Americans, he maintained, had been conditioned to “defend our master.” Confronting the consequences of African-American identification with Western culture was essential. Most “responsible Negro leaders” accepted the equation of U.S. capitalism and democracy and heeded the unwritten prohibition against criticizing American foreign affairs. Political maturity meant abandoning those shibboleths and adopting a new mentality. “Don’t let anybody who is oppressing us ever lay the ground rules,” Malcolm commanded.

Defending anti-imperialism was especially crucial at a time when Paul Robeson, Claudia Jones, and other outspoken black dissidents had been neutralized by the state. Malcolm stood at the helm of a younger generation of radicals—from Mae Mallory to Robert F. Williams—who challenged the accommodationist tendencies of the freedom movement. Like these contemporaries, Malcolm refused to accept the conventional parameters of Cold War dissent. His crusade to “internationalize” black America entailed a fundamental reframing of mass struggle. For him, no domestic “race problem” existed. There was only the global crisis of white supremacy.

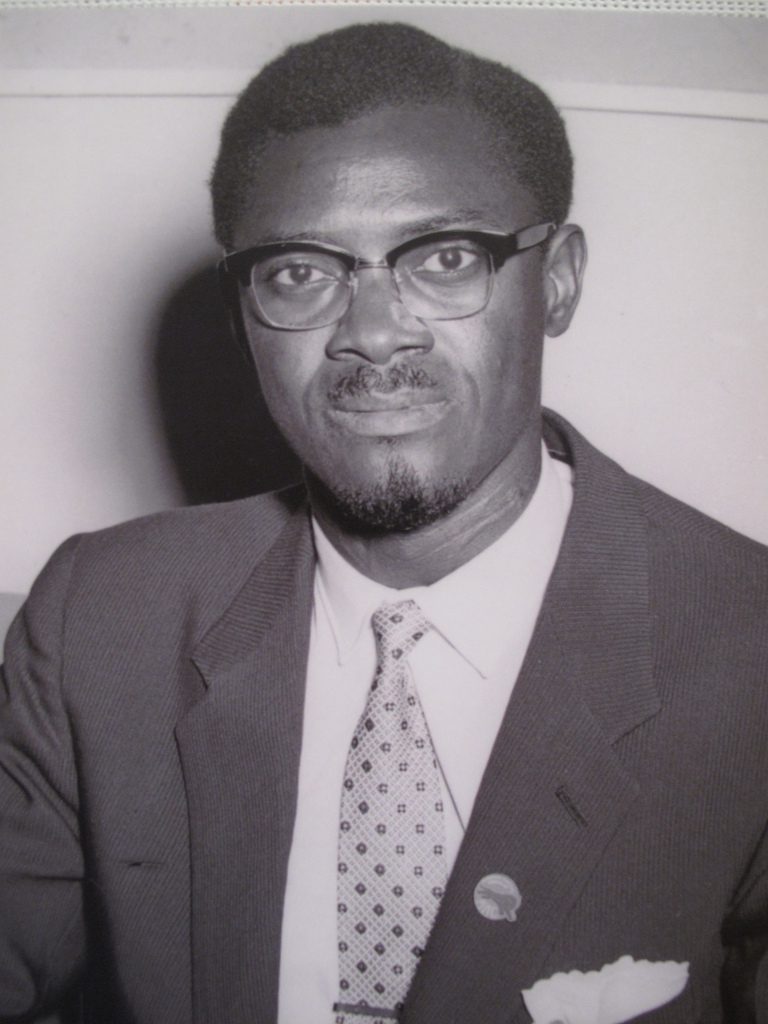

Confronting that crisis meant exposing the machinations of empire. Far from a beacon of democracy, the U.S. was the hub of Western imperialism. When one examined Cuba, Vietnam, or a host of other sites, one encountered the criminality of American foreign policy. For Malcolm the Congo offered the most damning contemporary example of U.S. imperial misdeeds. Patrice Lumumba, the rightful leader of that Central African nation, had been deposed and assassinated with American aid. Then, in an attempt to fracture the newly independent state and recapture its immense natural wealth, the U.S. and other Western forces had supported the slaughter of Congolese liberation fighters and civilians.

Malcolm’s task was to reveal the historical design behind such atrocities. Like South Africa, the U.S. was a nation rooted in the experience of settler colonialism. Its racism was a constitutive element of a legacy of conquest, not an unfortunate detour from the liberal democratic tradition. No less than the great powers of Europe, the U.S. was an expansionist force driven by the quest for domination and profit. The decline of Old World empires, Malcolm believed, had cemented America’s status as “the last bulwark of capitalism.” Yet he saw the nation less as a successor than as a collaborator with other Western regimes.

The U.S. was also a master of deception. The crumbling of European empires had enabled America to broaden its hegemony using “soft” methods, from the Peace Corps to what Malcolm called “dollarism”—the purchase of influence. Meanwhile an elaborate U.S. propaganda campaign had attempted to lure developing nations into the orbit of Western capitalism, in part by saturating them with tales of American progress in the area of race relations. Malcolm saw this maneuver as a case of skullduggery and he described it as such before audiences domestic and foreign. As he observed,

There is no system more corrupt than a system that represents itself as the example of freedom, the example of democracy, and can go all over this earth telling other people how to straighten out their house, when you have citizens of this country who have to use bullets if they want to cast ballots.

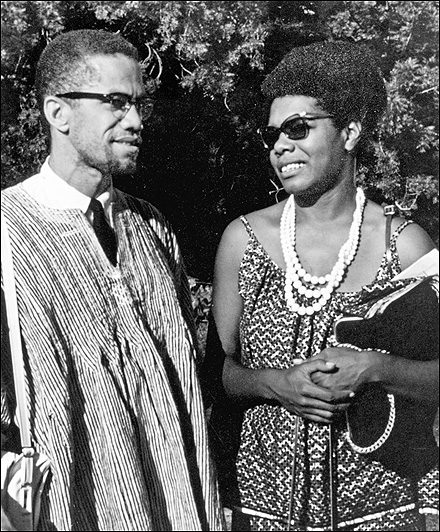

Malcolm also labored to discredit the notion that Africans and African Americans were strangers. The propagation of this myth, he explained, was part of a “gigantic design” to impede black transnational cooperation. African Americans were rediscovering ties of affinity with their “Motherland.” By communing with Babu of Tanzania, Ben Bella of Algeria, and a host of other freedom fighters, Malcolm had strengthened such bonds, rebuilding a relationship based on political mutuality while transcending the atavism and paternalism that had long colored African-American images of Africa.

At the same time, Malcolm forged alliances beyond the black diaspora, enlarging the possibilities of solidarity. He expressed camaraderie with Palestinians, Cubans, Chinese, and other Third World peoples, repudiating the idea of a planet divided between Eastern and Western blocs. Even his preferred term for Africans in America—“Afro-Americans”—connected disparate populations, encompassing many of the dark and marginalized inhabitants of the Americas. This was not just a semantic gesture. Malcolm was attempting to locate black America at the center of world revolution. No African-American movement would flourish, he argued, unless it was “tied in with the overall international struggle.”

For Malcolm, conquering the Cold War mindset was a matter of perspective. Those African Americans who saw their plight as a domestic affair would continue to view themselves as a minority. Those who looked beyond U.S. shores would identify themselves as members of “dark mankind.” The shift to “human rights” signaled this reorientation. Civil rights campaigns left African Americans at the mercy of American legal institutions. By contrast, Malcolm argued, the struggle for human rights enabled independent Africa, Asia, and Latin America to intercede on black America’s behalf at the United Nations. The involvement of such regions was vital because Malcolm planned to place black America’s plight before the international body. This was a wise strategy, he insisted, for it was not subject to the “internal goodwill of this country.”

Malcolm’s worldly vision did not free him from errors of analysis. In the mid 1960s the promise of decolonization was still fresh. One can understand why Malcolm overestimated radical solidarity as a force capable of surmounting ethnic, religious, and political divisions within the Global South. Though he grasped the link between international finance and underdevelopment, he failed to anticipate the extent to which modern capitalism would control emerging nations while fueling the corruption of postcolonial regimes.

Nevertheless, Malcolm was prescient in many ways. He predicted U.S. defeat in Southeast Asia, believing that the “rice farmers” of Vietnam would drive out the Americans just as they had expelled the French. He realized that the U.S. was far from invincible, despite its nuclear weapons and technological sophistication. It was doomed to lurch from skirmish to skirmish, engaging tenacious foes in costly battles while slowly collapsing under its own weight. America could destroy the world but it would never fully pacify or control it. It could encircle the globe with military bases but it could not escape its fate.

Malcolm often observed that, “chickens come home to roost.” He never doubted that the pursuit of imperialism would exact an enormous price. He would not have been surprised by America’s status as the world’s greatest arms dealer, or by the nation’s growing reliance on mercenaries, torture, and drones. Nor would he have lamented the decline of U.S. hegemony amid endless oil wars. Malcolm knew that the American people would pay for the nation’s sins, and that none of us would enjoy real peace or security so long as the quest for world domination continued.

Today Malcolm’s lessons are as relevant as ever. We still need a far more critical outlook on world affairs. The interminable “War on Terror” suggests that a new reorientation is necessary. We must broaden our scope. We must embrace anti-imperialist allies abroad while resisting empire at home. We must combat provincialism and seek psychological and political independence. For a new order is dawning. And as Malcolm reminded us, “You don’t know where you stand in America until you know where America stands in the world.”

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you Russell Rickford for a wonderfully clear and concise depiction of the world situatiion in connection with the story of truly great Malcolm X. As you say, more relevcant now than ever before. Also good that you recall Paul and Claudia Jones who fought as hard as they could and as long as they could. Prof. DuBois could well be added. And, fascinating for me, towards the end of his life Dr. King came to almost the same conclusions, as shown in his Riverside speech. Perhaps that is why he, like Malcolm, did not live very long.

Thanks and greetings (from an ex-pat in Berlin, who has also written with much the same message on this subject (but in German in the GDR).

Victor Grossman