Pedagogy for the World: Black Studies in the Classroom and Beyond

One of the original aims of Black Studies (and the related fields of African-American and Africana Studies) was its pedagogical mission—to inspire people to learn deeply and critically about the African Diasporas’ histories and contemporary social formations; to develop an incisive critique of Western civilization; and to create and sustain black culture as an alternative source of power in a world fundamentally shaped by anti-black racism.

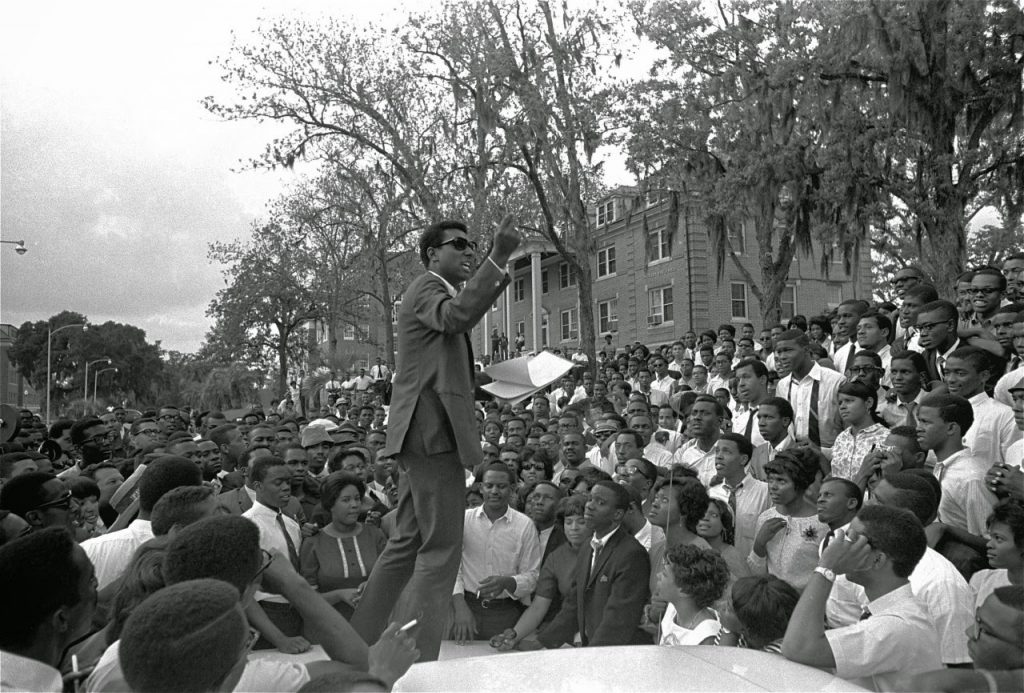

The educative aims of Black Studies—to create autonomous spaces in which to define what intellectual self-determination might look like and to practice it—were born of the struggles of students and faculty to remake college campuses and with them the wider world. Student activists pushed their campuses along the contours of social justice, self-determination, anti-war politics, and anti-capitalism. Black student activism from campuses as diverse as San Francisco State University and the University of Virginia pressed administrators not only to matriculate more black students and hire more black faculty, but also to support the creation of robust institutes, departments, and colleges where educators could arm students for intellectual battle in their various chosen fields from social work and medicine to community organizing and liberatory sociology.

This unique history of the inter-discipline continues to shape the distinctive ways that its interlocutors teach students. Black Studies practitioners often educate students not only in the frame of the traditional academy, but often with the aim of remaking the world to be more just and hospitable for the peoples of the Diaspora. In what follows, I draw on the wisdom of my elders—those that serve as bridges between ancestors and me rather than simply those who have been here longer than I have—to think about the continuation of the radical enterprise of Black/Africana/African-American/African-Diasporic studies in our deeply troubling political moment. I draw on my own personal journey from student to educator through Black Studies, highlighting the pedagogical work of scholars who educated me and ending with a brief account of the ways this has shaped my approach to Black Studies in my most recent course. My own personal journey into Black Studies offers glimpses into the transformative power of the field to not only provide training for a field of study but to serve as a means of empowering people to build the world we need.

My two primary mentors during my undergraduate education, Claudrena Harold and Wende Marshall, introduced me to a conceptualization of Black Studies as not simply the study of black people, but rather the concerted effort to critically appraise the world from the vantage of some of its most marginalized actors and to use that knowledge for empowerment and action. Harold taught that Black Studies was not dependent on the traditional classroom or full funding to be effective. Often really generative work flourishes in the shadows. While the Carter G. Woodson Institute and the program in African American Studies before it have not always enjoyed wider institutional support, it has always been a vibrant intellectual space, benefitting from superb educators like Joseph Washington, Vivian Gordon, and Reginald Butler.

Harold built on their pedagogical legacy, as well as others who preceded her, to inspire us to study deeply. She helped my contemporaries and me to view Black Studies as a radical field of study with implications for the wider university and the world. She taught a memorable course, Black Power, centered on the threads of radical labor politics and incisive critiques of racial capitalism. Yet our conversations about organizations like the League of Revolutionary Black Workers were never relegated to the past. As we dined at Charlottesville’s Mel’s restaurant, we often discussed what learning about these histories might mean for action in the on-campus Living Wage Campaign, in student-led efforts to transform the University, or in our efforts to strengthen local politics.

Critically, Harold brought us together across the academic hierarchy of faculty, postdoctoral fellow, PhD candidate, administrative staff, and undergraduate, and that was as much a part of the pedagogy as the specific histories that were part of her expertise. Harold viewed us all as qualified to do the generative work of Black Studies, later remarking, “I always viewed you guys as colleagues. My goal has always been to build community and by extension create the conditions of possibility.” Harold, often in the quiet, intuitive mode through which she conveys deep wisdoms, got us to understand that Black Studies was about producing culture. Harold never allowed us to settle with our answers and part of her pedagogical impulse was to get us to incessantly question inherited wisdom.

Wende Marshall was not centered in Black Studies in precisely the same way at UVA. After working as a community organizer in Central Harlem, she studied Black Liberation Theology with James Cone at Union Theological Seminary before pursuing a PhD in the anthropology of Hawaii. Yet, Marshall’s Health of Black Folks was a famous part of the curriculum at UVA during my time there. That course produced innumerable physicians and healers who understand their work as tied to social justice and healing as an inter-generational process that cannot be accounted for in the frame of the individual body alone. In fact, it convinced me to abandon my pursuit of medicine and adopt the understanding that organizing and attention to historical trauma were part of how I wanted to do healing work in the world. Marshall also taught a course that forever shaped my political consciousness, Community Organizing, in partnership with Charlottesville’s Quality Community Council and the statewide Virginia Organizing Project.

Marshall held the course at the Quality Community Council and co-taught it with members from the two organizations. We effectively planned and executed a hearing on mental health services in the wake of a mass murder at Virginia Tech. The new funding that was being opened, in a state that at the time ranked 49 of 50 for mental health services funding, was taking carceral forms and we meant to interrupt that. It was one of my first experiences with people power and it further reinforced my understanding that Black Studies held the power to transform the world beyond the university.

Marshall has continued her praxis of Black Studies as a radical social vision meant to change the world, despite being denied tenure at the University of Virginia. She has continued to fight as one of the primary organizers of Stadium Stompers, an organization that brings together black North Philadelphia community members, radical student organizers, cultural workers, and adjunct faculty to interrupt Temple University’s bid to displace thousands with a football stadium. Stadium Stompers is working across these wide differences to reimagine the community beyond exclusion, gentrification, and displacement. What happens there will undoubtedly shape the possibilities for urban futures well beyond Philadelphia and will continue to serve as a testament to the possibilities of Black Studies pedagogy in action beyond the classroom.

On December 20, 2016 Stadium Stompers members closed the major north/south thoroughfare by Temple, Broad Street at Cecil B. Moore, to draw attention to their continued work of reimagining North Philadelphia as more than an elite enclave. Many of Marshall’s students and former students were involved and this signals that Black Studies as a radical pedagogy is part of the ongoing possibility for a world dislodged from the logics of racial-capitalism.

The lessons they both taught and continue to teach me in the meaning of Black Studies have influenced how I approach teaching Africana Studies, now that I have students. This past semester I taught Race, Feminism, and Resistance at Smith College—a course introduced by historian Paula Giddings. In this course I sought to incorporate the lessons Harold and Marshall, who taught me Black Studies was the inter-discipline where we study deeply, move culture, and inspire radical social visions for a different kind of world. I had three sets of students who focused intently on the work of healing as part of the capacity of Black Studies to transform the world. Fulani Oghoghome created Sisters of the Yam, a regular space at Smith for black students to be vulnerable and to engage in self-healing, as her final project. Gaïana Joseph, who is the chair of the wellness committee in the Black Student Association on campus, created a stunning documentary, Quiet, that centers on interviews with black Smithies in the botanical gardens discussing emotions that they are often shamed from expressing in popular culture and by other members of black communities. The result is a beautiful portrait of the interior lives of black folks discussing what it means to strive to live in their fullness. Finally, Temar France and Lillie Lapeyrolerie produced a beautiful fictional film, A recipe for wellness, from footage they shot of both Oghoghome’s and Joseph’s projects. It is a poetic synthesis in which the narrators ponder conjuring and healing work on a contemporary campus out of the long tradition of alternative black healing that for them is a primary lesson of Black Studies.

As Harold and Marshall taught me, Black Studies is the generative enterprise of studying the world as it is and creating the conditions of possibility for a new one within and beyond the university. My time at the University of Virginia irrevocably shaped my outlook on the possibilities for social transformation in the hands of people armed with the critical insights of the inter-discipline. Black Studies has always been more than simply the study of black people. Indeed, Black Studies embodies possibilities for a different world.

J.T. Roane is a McPherson/Eveillard Postdoctoral Fellow at Smith College. He is primarily interested in questions of place in relation to black histories and is currently working on a manuscript titled “Sovereignty in the City: Black Infrastructures and the Politics of Place in 20-Century Philadelphia.” Follow him on Twitter @JTRoane.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you: it’s important to think about the motley conditions and aims of pedagogical praxis, particularly in the light of sundry historical and contemporary injustices and hindrances to individual and collective self-realization in the deepest and widest sense. Academics are not always and everywhere at the same time “intellectuals” with a keen appreciation of the burdens, complexities, and tasks that are intrinsic to moral and political responsibility (as other posts on this blog have reminded us), so it’s refreshing and invigorating to see concrete examples of what it means to be both an academic and and intellectual, both inside and outside the formal educational system.

[The essay by A. Muhammad Ahmad on The League of Revolutionary Black Workers that is linked to has numerous typos. I’m putting together a corrected version as a Word doc. that I’ll pass along to anyone interested (you can find an e-mail address for me at the Ratio Juris blog or my Academia page).]

The pedagogy of the Black Studies Educational Movement is an excellent analysis of the course of action that we, as Black people, must focus on during the incoming administration.