Activism and “Good Trouble” in the March Trilogy

This guest post is part of our new blog series on Comics, Race, and Society, edited by Julian Chambliss and Walter Greason.

In the pages of John Lewis’s graphic novel, March: Book Three, Civil Rights leader C.T. Vivian faces down the sheriff and other authority figures at the Dallas County Courthouse in 1965. As a backdrop to this confrontation, reporters’ flash bulbs burst as policemen attempt to corral the crowd away from the building. The rain slashes violent vertical lines across asymmetrical panels as Vivian struggles to complete his rebellious act: registering to vote.

“If we’re wrong,” Vivian asks the sheriff, “Why don’t you arrest us? It’s a matter of facing your sheriff and facing your judge. We’re willing to be beaten for democracy.” Cutting through the rain and the divisions on the page is John Lewis’s narration, explaining Vivian’s dedication to equality: “He’d been there in Nashville in 1960, he was with us on the Freedom Rides. He did time in Parchman. He was in Birmingham in ‘63, in Mississippi in ‘64, and now here he was again—making good trouble, necessary trouble.”

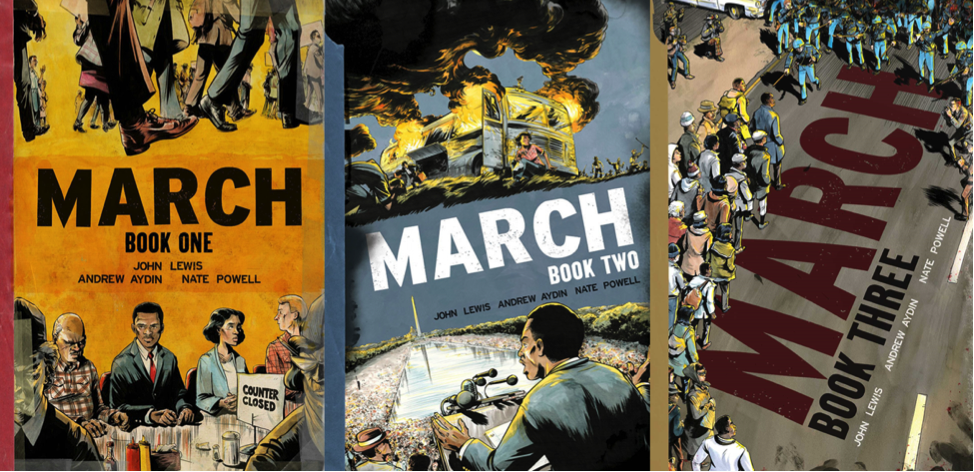

In this post, I place March within a tradition of comics illustrating and inciting “good trouble,” Lewis’s catchphrase to describe what, for him, has been a lifetime of peaceful protest and civil disobedience. Leading a sit-in this summer at the House of Representatives following the Orlando massacre, Lewis described the impetus behind good trouble to fellow occupiers: “There comes a time,” he explained, “when you have to say something, when you have to make a little noise, when you have to move your feet… Now is the time to get in the way.” In fact, March does more than make a little noise: Along with co-author, Andrew Aydin, and artist, Nate Powell, Lewis has received numerous distinctions, including an RFK Prize for March: Book One and an Eisner Award for March: Book Two, an honor that Esquire‘s Jonathan Valania likens to “the Pulitzer Prize of comic books.” Most recently, Book Three won a National Book Award.

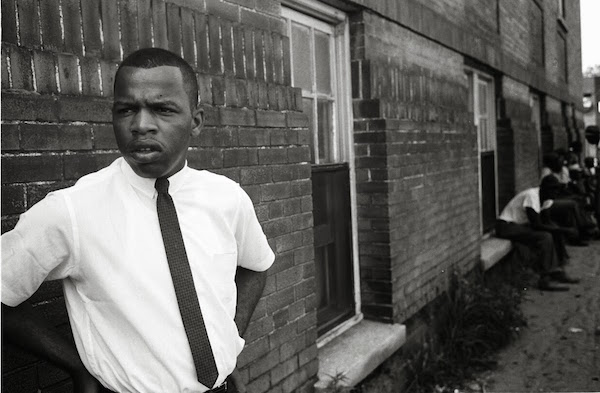

Finally, at the 2015 Comic Con, Lewis donned a trench coat and backpack—a cosplay mirror image of his outfit on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma—and led a march through the convention center followed by his fans, many of whom were children.The phrase “good trouble“ embodies John Lewis’s tumultuous life story, the highlights of which include leading the Nashville Sit-ins as a teenager, participating in the 1961 Freedom Rides, chairing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1963, and marching in the face of violence for voting rights on “Bloody Sunday” in Selma in 1965.Georgia would elect Lewis to Congress in 1986, where he remains the last living member of the Big Six leaders which included A. Philip Randolph and Martin Luther King, Jr. who organized the 1963 March on Washington. Lewis’s biography would find its way to the pages of a bestselling graphic trilogy, March.

March tells the story of Lewis’s involvement in the Civil Rights movement and the fight for suffrage, but it also advocates for good trouble even as those same rights continue to be under threat today. The trilogy presents Lewis’s story in intricate black-and-white images, words spilling over the gutters and across panels, far-flung from the stable, rectangular panels of more “traditional” comics. Some words and actions are illegible, speaking to the chaos often characterizing this period. Readers are transported to stark scenes of racism and violence, as well as Lewis’s dogged resolve to march despite the danger. Just as the words themselves struggle to break free from the constrictions of panels and pages, the voices of Lewis, Jim Lawson, Amelia Boynton, and others continue to reverberate in more recent events and protests.

Lewis was himself influenced by a comic that embodies the concept of “good trouble.” The idea for the trilogy came when staffers teased Aydin, his then-press secretary, for spending his vacation at a comic convention. Coming to Aydin’s defense, Lewis recalled, “I read a comic book called Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story that told the story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. And this little comic book inspired me and many other young people to get involved in the Civil Rights movement.” Published by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the widely-distributed comic features King’s early life and details of the Civil Rights movement, ending with an examination of the “Montgomery Method” of nonviolent activism.

Aydin identifies the comic as the model for March, crediting the former’s “role in some of the earliest sit-ins, as early as 1958. It had been used by students leading the sit-in movement, and… spread throughout the country. We felt it was very important to use history as our guide, as John Lewis did, and frame the story this way.” In fact, the 1957 comic crystallized the movement for Lewis, giving insight and direction. (Montgomery Story played a similar role in the 2011 revolution in Tahrir Square.) The significance of nonviolent protest is a prominent theme both in The Montgomery Story and March, which motivates a new generation of readers to continue Lewis’s struggle for equality.

Comics have always portrayed struggles for equality, even in the medium’s most prominent genre: the superhero comic. For example, Issue #76 of the Green Lantern, “No Evil Shall Escape My Sight” (1970), portrays the superhero grappling with African American inequality: A man draws attention to his fight for the “blue skins,” “orange skins” and “purple skins,” even as he “never bother[s] with the black skins.” Today, superheroes of color continue to emerge in “conventional” comics: Robert Morales and Kyle Baker unveil the story of Isaiah Bradley, the black protagonist of Captain America: Truth. The series complicates Captain America’s legacy, placing Bradley within the context of eugenics and the WWII Tuskegee syphilis experiments as a test subject for the serum that gave Captain America his superpower. Meanwhile, in a different kind of hero tale, James Sturm and Rich Tommaso depict the story of baseball legend Satchel Paige to highlight Jim Crow and southern race interactions. Envisioning the athlete through the eyes of fictional rookie, Emmet Wilson Jr., the authors show readers the pervasiveness of Jim Crow inequality.

In fact, one significant characteristic that Truth and Satchel Paige share with March and other good trouble narratives is the message of shared responsibility: For instance, Captain America fans enjoy Steve Rogers as the titular hero specifically because Truth’s Isaiah Bradley struggled before him. In fact, Rogers finally realizes the true cost of his powers and visits Bradley, only to discover that the serum has depleted Bradley’s mental faculties. In March, the story takes on the Lewis’s perspective, even hovering at child’s level for his earlier days on an Alabama farm. However, March also does not shy away from taking on the gaze of Americans terrorizing protesters, blocking entry to voters’ registration lines, and attacking marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. March reminds us that we have a choice on where we stand, and—if we are to follow Lewis’s lead—we should stand in the way of injustice and oppression.

Graphic memoirists such as Marjane Satrapi and Art Spiegelman also employ the good trouble approach. Satrapi, for instance, allowed artists to update her controversial autobiography about Iran in the Islamic Revolution as a webcomic, Persepolis 2.0, about Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s Iran. Meanwhile, in Volume 2 of Maus, Spiegelman’s Holocaust comic, author-protagonist Artie reacts with self-conscious horror to Volume 1’s success: At his drafting table, Artie is surrounded by bodies of Holocaust victims. Rather than allowing readers distance from the repulsive scenes on the previous pages, Artie’s guilt inspires readers to question their own motives and responsibility in reading.

By their nature, good trouble narratives are hard to categorize, deliberately spanning multiple genres. Joe Sacco‘s coverage of Palestinians under Israeli occupation—in comics such as Palestine—are both narratives and journalism, while Seth Tobocman‘s War in the Neighborhood is part-story and part-political manifesto. Writing in 1946, Miné Okubo detailed her life in a Japanese American WWII concentration camp in Citizen 13660, a book that is a memoir, archive, and historical document. The fight for equality in popular culture—including comics—means that boundaries of genre and division are bound to be broken.

Addressing newly-minted graduates in Wisconsin, Lewis stated, “History will not be kind to us. So you have a moral obligation, a mission and a mandate, to speak up, speak out and get in good trouble…. You must never, ever give in. You must never, ever give out. We must keep the faith because we are one people. We are brothers and sisters. We all live in the same house: The American house.” Even now, Lewis understands that his house is in jeopardy. As the fight for equal representation in comics, in politics, and in social justice continues, John Lewis stands, a real-life superhero.

Leah Milne is an assistant professor at the University of Indianapolis, where she teaches literature and composition. She earned a doctorate in English from the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, in 2015. She specializes in 20th century multiethnic American literature. Follow her on Twitter @DrMLovesLit.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.