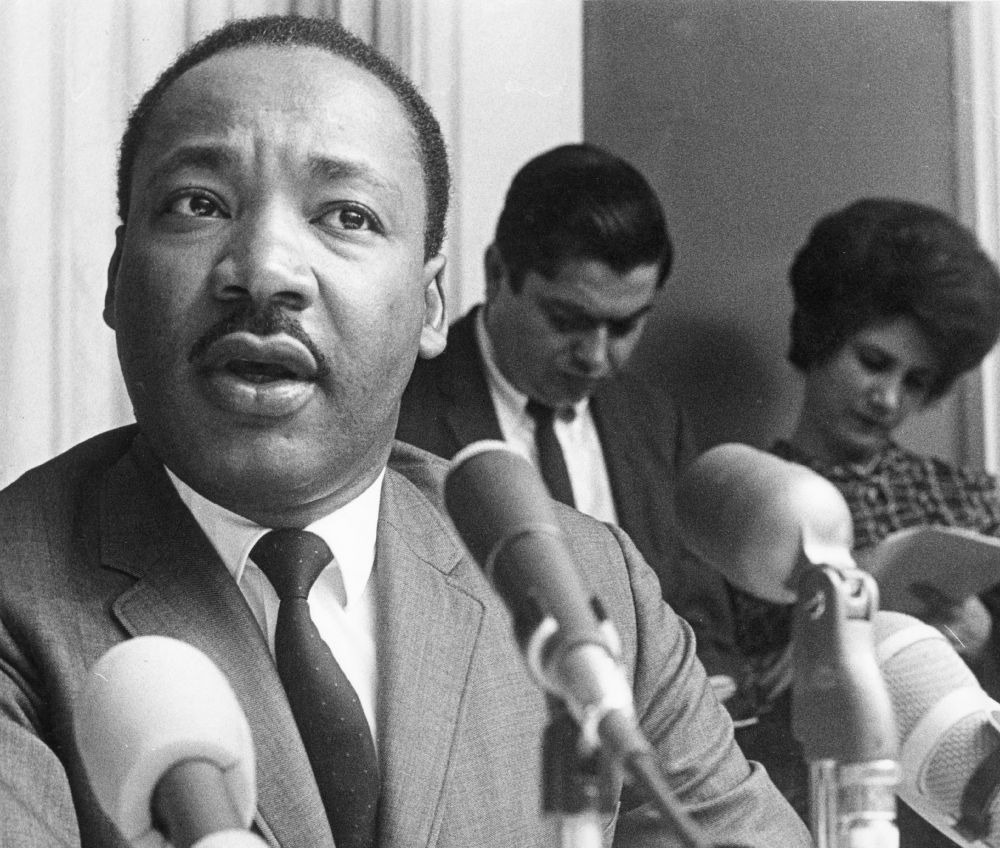

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Challenge to his Liberal Allies

“We do not need allies more devoted to order than to justice,” Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in the spring of 1964, refusing calls from moderate Black and White leaders to condemn a planned highway “stall-in” to highlight systemic racism in New York City. “I hear a lot of talk these days about our direct action talk alienating former friends,” he added. “I would rather feel they are bringing to the surface latent prejudices that are already there. If our direct action programs alienate our friends … they never were really our friends.”

In popular memory, Dr. King has been trapped in the South. While our vision of King’s politics has widened to encompass his criticism of the Vietnam War and his organizing of the Poor People’s Campaign, his critique of Northern racism and attention to police brutality nationwide are routinely missed — and too often, Dr. King is rolled out to chastise contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter for their tactics and approach.

Yet, King highlighted the venality of more “polite” forms of racism and challenged Northern liberals to address racism at home — and not just in the South. Violence and hate-filled rhetoric were not the only methods by which White supremacy was maintained. King identified how people, including those who may have deplored Southern injustice, maintained the racial status quo. Moderates and liberals deployed “both-sidesism,” argued that time would solve the problems of racism, cast disruptive protest as unwise and unreasonable and embraced ideas like the “culture of poverty” to justify strong-arm policing and explain away inequities in their own cities. King’s analysis is particularly urgent now, given the ways the far right’s overt White supremacy threatens to overshadow other forms of racism — and given the problematic misuse of King’s legacy to undermine the approach of Black Lives Matter.

From the beginning of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, King made clear that systemic racism was a national problem. He called on Northern liberals not only to decry the South but also clean up their own cities. In May 1957, King’s speech at the Prayer Pilgrimage in Washington D.C., arguably his first national speech, challenged the superficiality of liberal commitments: “What we are witnessing today in so many northern communities is a sort of quasi-liberalism which is based on the principle of looking sympathetically at all sides that it fails to become committed to either side.” The next year, in his first book Stride Toward Freedom (1958), which laid out the lessons of the Montgomery bus boycott, King underlined the “pressing need for a liberalism in the North that is truly liberal, that believes in integration in his own community as well as in the deep South.”

As he crisscrossed the nation in the early 1960s raising money and attention for the Southern movement, he joined Northern struggles against school and housing segregation, job discrimination and police brutality. In 1961, he warned Black New Yorkers, “There will be those who tell you to slow up … to cool off …. you cannot slow up your determination.” In Seattle, he homed in on the myth “that time will solve problems” many liberals seemed to prefer regarding racial issues at home. He joined protests against school segregation in Chicago and Los Angeles in 1963 and traveled repeatedly to California in 1964 to join the fight against Proposition 14, which sought to repeal the state’s recently-passed fair housing act. Again and again, he called out the gap between Northerners’ professed anti-racism and their unwillingness to see, let alone address, deep inequalities at home. Again and again, like the Northern activists he joined with, he was dismissed, disparaged and red-baited for this work.

A movement had been growing in New York challenging the city’s segregated schools. Most White New Yorkers responded with disregard or disgust. On February 3, 1964 nearly half a million students and teachers stayed out of New York City’s schools to protest the lack of any plan for desegregation a decade after. It was the largest civil rights demonstration of the era.

The New York Times lambasted the protest as “violent” and “reckless” and dismissed civil rights demands as “unreasonable and unjustified.” Two months later, King responded to such critics in the Amsterdam News. The “school boycott concept in practice has proved very effective in uncovering the injustice and indignity that school children in the Negro-Puerto Rican minority community face,” King wrote, “punctur[ing] the thin veneer of North’s racial self-righteousness.” Responding to the criticism that such disruptive tactics were unnecessary and unreasonable, King flipped the script back on public officials and White residents, calling it the “harvest of past apathy to tragic conditions that were allowed to exist without any serious concern.”

While Northerners cast their segregation as “de facto” and saw it as “natural” and “accidental” (as New York’s superintendent did) rather than systemic, King called it “a new form of slavery covered up with certain niceties.” When commentators began talking about a “backlash” against civil rights given Alabama Gov. George Wallace’s support outside the South in the 1964 presidential primary, King made clear that it was actually a frontlash — since many Whites “had never been committed” to civil rights in the first place.

In July 1964, when the police killing of 15-year-old James Powell led to six days of uprising in Harlem, Mayor Wagner invited King hoping he would calm the unrest. Instead, King made clear that “profound and basic changes” were needed around jobs, housing, schools and policing to avoid further uprisings, urged the officer’s suspension and suggested the city would benefit from a Civilian Complaint Review Board to oversee the police department. He was nearly run out of town by city leaders.

The same thing happened again a year later after the Watts uprising. King went to Los Angeles and sat down for a three-hour meeting with Mayor Yorty and Police Chief Parker — reiterating community calls for Parker’s removal, highlighting patterns of police brutality and calling for a Civilian Complaint Review Board. Mayor Yorty complained of “unfounded charges of police brutality,” accused King of advocating Black “lawlessness” and told reporters that King’s visit had done “a great disservice to the people of Los Angeles & to the nation.”

Three months later, King highlighted his disillusionment with officials like Yorty and Wagner who “welcomed me to their cities and showered praise on the heroism of Southern Negroes. Yet when the issues were joined concerning local conditions, only the language was polite; the rejection was firm and unequivocal.” He zeroed in on the differential national outrage at police brutality in the South versus the North, despite Black protest: “As the nation, Negro & white, trembled with outrage at police brutality in the South, police misconduct in the North was rationalized, tolerated, & usually denied.”

King also challenged the tendency to cast Black behavior as the problem, rather than investigating the structures of racism in the North. “Many whites who oppose open housing would deny that they are racists. They turn to sociological arguments … [without realizing] that criminal responses are environmental, not racial.” Upending the idea of “Black crime,” King reframed the question by highlighting White illegality and malfeasance that produced northern ghettos: “When we ask Negroes to abide by the law, let us also demand that the white man abide by law in the ghettos. Day-in and day-out … he flagrantly violates building codes and regulations; his police make a mockery of law; and he violates laws on equal employment and education and the provisions for civic services.” With the phrase “his police,” King made clear that the police were not there to protect or serve the Black community but served as a mechanism of control.

Across his adult life, King saw America’s race problem as national and highlighted northern hypocrisy in praising the movement in the South while decrying Black activism at home. He critiqued public officials, journalists and scholars who preferred to wait on “time” and to focus on Black behavior and “crime,” rather than White hoarding, state policies, and abusive policing that produced widespread inequality in the liberal North. Regularly criticized about the disruptive tactics he supported, as Black Lives Matter often is today, King understood that disruption was necessary to unsettle the comfortableness of injustice and its often “polite” accomplices. An honest reckoning with King’s legacy and what it asks of us today must begin with King’s long history of highlighting police brutality outside of the South and his insistence that Northern liberals see their own racism and push for change at home in their own institutions.

**This piece is reprinted in collaboration with The Washington Post’s ‘Made by History.’