A Tale of Two Graffitis: The American Tag and the Brazilian Pixação

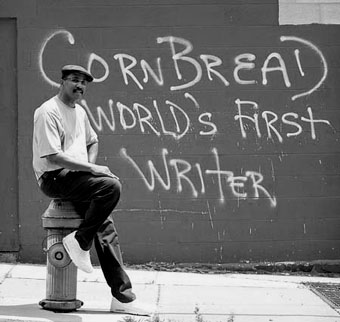

In 1970 on the U.S. East Coast, before there were murals or graffiti “pieces,” even before people began experimenting with bubble letters and stylish numbers, there was the “tag,” and the tag was everything. A stylized signature used to mark trains, walls, stalls, halls, bus stops and more, the tag was the first thing an aspiring “writer” had to create and disseminate to make a name for his- or herself. Made famous on New York City trains, the tag as we know it traces its lineage back to 1967 Philadelphia, when a young Darryl “Cornbread” McCray became known for writing “Cornbread Loves Cynthia” all over the city in hopes of attracting the young lady’s attention. Later on, McCray shortened the tag to just “Cornbread,” and over the next few years he left his tag everywhere, from the side of the Jackson Five’s 747 to the side of an elephant at the city zoo. Unquestionably, Cornbread won local fame, but the practice of tagging would not stop there. As McCray himself puts it in one interview, other folks thought “if he can get that from writing on walls, then so can I.”1 Tagging then spread beyond Philly to New York, and by the early 1970s the tag would not only include the writer’s name but also their street number. Thus the first kings and queens of graffiti would be writers like Lee 163, Barbara and Eva 62, Charmin 65, and Taki 183.

According to some writers and photographers like Martha Cooper, we are witnessing a “return of the tag” in contemporary graffiti culture. This is in part a delayed reaction to the increased popularity, commercialization, and government co-optation of graffiti that has been unfolding since the mid-1980s. In fact, the first mural arts projects developed in cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York during this period were geared towards rehabilitating graffiti “vandals” by employing them in community artworks geared towards local economic revitalization projects. This coincided with the opening of galleries dedicated to graffiti “pieces” (short for “masterpiece”) of singular, well-known writers, as well as the development of neighborhood arts associations that commission known writers to paint murals. The proliferation of such spaces now grants some artists not only legal security but also more time and permission to construct elaborate designs, leading public spectators, building developers, and investors to consider graffiti murals not only as fine art with the requisite amount of “time” invested in the product, but as commodifiable culture that can be sold to hipster, young professional, and millennial markets.

Despite there being several legal avenues for writing and painting “pieces” on walls, the fact remains that only a select number of writers can hope to be commissioned or be offered mural work. Commissioned work not only introduces questions of capital into graffiti, but also questions about privilege and opportunity. Thus, it should come as little surprise that there are many artists and writers who still desire or prefer graffiti scenes that remain outside of these legal networks, and the tag, as something that remains noncommissioned and that still contains a strong element of illegality and transgression, works for this purpose.

In Brazil, a parallel but dissimilar phenomenon is taking place. If you were paying attention to the geographic backdrop of this year’s Olympics, you certainly noticed the beaches, the mountains, and the sun. You may have even seen the some of the commissioned murals and graffiti pieces that were likewise a part of Rio’s promotion of its beauty. What you likely did not catch a good view of was the proliferation of “pixação” (or more properly “pichação”), a form of writing on the walls that for many street artists has come to signify a stand against global capitalism, artistic commercialization, and social injustice.

Though the term is rooted in the Portuguese verb “pichar” (to cover with tar), as Marcio Siwe details in “Pixação: the Story Behind São Paulo’s ‘Angry’ Alternative to Graffiti,” pixação as we know it comes out of the 1980s Brazilian reception of imagery associated with heavy metal music. In particular, the album covers of heavy metal bands from that era typically used Old-Norse-looking letters in their titles and band names, and this appears to have made a strong impression on a number of future writers. So strong was this impression that when the country officially began transitioning from dictatorship to democracy in the mid-1980s, young activists and writers began to make statements on walls and buildings using letter styles similar to those that had so captivated them on those album covers. Pixação thus developed through a combination of public political critique, property vandalism, and artistic imitation of ancient script.

Because pixação writers mostly stick to less-stylized words and letters and only seldom draw or paint images to accompany their work, much has been made in the past about the equivalence between pixação and the tag. Indeed, a quick search of pixação returns a link to a Wikipedia page where the form is described as “tagging done in a distinctive, cryptic style…” Mainstream media, public opinion, and law enforcement all treat pixação as criminal vandalism while seeing graffiti pieces as fine art, somewhat mirroring the distinction between murals and tags in the U.S. In fact, the distinction between fine art and criminal art may be more rigid in Brazil, where the city government began pushing a “Não Pixe, Grafite” (“Don’t do Pixação, do Graffiti”) campaign in 1999. More recently, in 2009 the Brazilian government passed law 706/07, making street art and graffiti legal on designated city property and on private property with consent of the owner. Through this same law, however, pixação remains explicitly illegal. Thus, the fact that tags and pixacões are both rooted in letters and words rather than pictures, and the fact that both are hounded by accusations of vandalism while murals are hailed as creative work, has led a number of observers to posit the notion that pixação is merely a younger sibling of the tag.

Yet as Siwe’s article notes, though “pixação” chronologically came about after graffiti was already a global phenomenon, there are many people—from pixação writers and admirers to detractors—who claim that graffiti and pixação are two separate forms. This is a sharp difference between pixação writers in Brazil and taggers in the U.S. Indeed, you may be hard-pressed to find a tag artist who does not see their work and their person as honoring the roots of modern graffiti. Pixação writers, on the other hand, claim their work is more authentic and political than that of graffiti writers, who are depicted as commercialists whose work is easily appropriated and utilized for middle-class gentrification and beautification projects. Here, we must consider that the same processes of commercialization introduced into the US graffiti scene in the 1980s were in many ways responsible for how graffiti was packaged and exported globally from New York to other cities. Thus, while graffiti writers of the ’80s and ’90s in Brazil were certainly aware of graffiti’s links with hip-hop, many were introduced to graffiti after it had traveled and gotten mainstream recognition through galleries and thus after it was established as a bona-fide arena where artistic skills could be commodified in the service of global recognition. If in the U.S. context the return of the tag can be vocalized as going back to the roots and the “buttery essence” of graffiti (as the writer Earsnot exclaims in the film Infamy), then the turn to pixação in Brazil seems to be spoken of as a demarcation between the kind of writing on the wall that came to Brazil through globalization and the kind of writing on the walls that some would like to define as the future of street art in Brazil.

In short, though pixação writers in Brazil and tag-enthusiasts in the U.S. find similar shortcomings in the commercialization of graffiti, they are currently expressing two different reactions to this phenomenon. As scholars, journalists, and activists work to understand the increasing importance of graffiti in the global world, we must pay attention to not only the differences in style between the different forms/names of writing on the walls in different countries, but also to the political moments that shape participant experiences and interpretations of these styles. This is not just a point to remember in thinking about graffiti developments in the Western World. WOW (Women On Walls) has recently emerged as a pivotal organization in Egypt facilitating political dissent through graffiti.

Rather than trying primarily to understand this movement in relation to what we know about U.S. or Western graffiti, we would do better to consider how that country’s history, replete with its own antecedent forms of wall writings, has engaged with, made sense of, and redeployed writing on the wall for the contemporary moment.

Greg Childs is Assistant Professor of History at Brandeis University. He is currently completing a book entitled Seditious Spaces, Public Politics: The Tailor’s Conspiracy of Bahia, Brazil and the Politics of Freedom in the Revolutionary Atlantic.

- David Cane “Cornbread-The first Graffiti Writer” http://www.theoriginators.com/cornbread-the-1st-graffiti-writer-words-by-david-cane/. ↩

Good book title; I look forward to reading it when published. Apt comparisons with Brazil, needed and inevitable in a globalized world. But some details are wrong and need correction before a final draft . For instance:

*1970 on the east coast was not before murals. See On The Wall. Several were painted there before 1970, also elsewhere.

*Tagging goes back much further than ’67 in Philly, depending on definitions.

*First mural projects developed in “cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York.” “Like” ???

The first mural org was in Chicago, earliest mural in Chicago in ’67, but Olivia Martinez painted one in Denver in 65. (not sure of name). Philly murals begin early, but PAGN, which has become PMAP, did not begin until the 1980s.

Some early mural work in East Los was supported as anti-graf by the LAFD. See Give Me Life, forthcoming.

As we enter the 21st century, “mural” now mostly means “spray can.” Blurring definitions is not helpful; needs careful clarification. Besides On the Wall, check Philly books, Toward a People’s Art, Urban Art Chicago, San Francisco Bay Area Murals.