Visualizing the End of Human Captivity

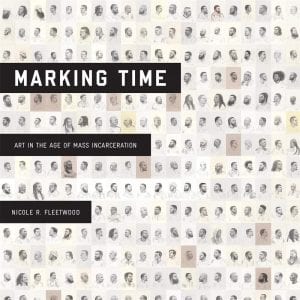

What happens to contemporary art when we foreground conditions in which expressive autonomy incites repression, surveillance, and severe punishment? What does it mean to create through circumstances where risk and violence fundamentally structure process, material, and form? What terms of analysis are available for creative practices that defy the conceits of Western aesthetics? Nicole Fleetwood’s Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Harvard University Press, 2020) takes up these questions through an intimate study of the “aesthetic engagement and knowledge worlds” of incarcerated artists and their collaborators (3). From portraiture and covert filmmaking to mixed media collage, Fleetwood gathers a remarkable body of visual art created across various states and sites of confinement. Within penal captivity, she stresses, there remains a counter-pulse, a relentless commitment to “create, to forge relations, and to embody and represent one’s life under unimaginable conditions” (19).

Indeed, Fleetwood amplifies this commitment to create through the routine violence of the prison and its sprawling network of institutional counterparts. She curates visual testimony made “from isolation, from torture…from spaces where people are rendered dead or dead-in-waiting as punishment for their very existence” (18). She intervenes on the visual economy of captivity, the distribution and circulation of “rehearsed images” – mug shots, barbed wire, metal doors – that legitimate the punitive state and establish the prison as fundamental to the current political order (15). And through all this, the prison emerges as a site of prolific cultural production, one disavowed by the institutional stewards of the contemporary art world for the very fact that prison art undermines the prerogatives of the museum and its affiliates – these technologies of aesthetic and political regulation.

Marking Time conceptualizes visuality as a tool of state authority, on the one hand, and a medium of radical prison praxis that refuses viewing relationships structured by state power on the other. For Fleetwood, carceral visuality refers to the state’s capacity to determine “who sees and what can be seen” and to render “incarcerated people both invisible and hyper- visible, but also unseeing and unseen” (15-16). Carceral aesthetics, however, names the forms of art-making that emerge from and across the cells, holds, and recesses of the penal landscape. They are practices of relational and affective possibility that assemble “provisional publics” or spaces of belonging, exchange, and self-making that exceed carceral divides and undermine state mandated isolation and control (21). As survival strategies, modes of critique, and methods of clandestine worldmaking, these creative practices defy the terms of obliteration and incapacitation the state demands while advancing gripping forms of aesthetic experimentation.

Marking Time conceptualizes visuality as a tool of state authority, on the one hand, and a medium of radical prison praxis that refuses viewing relationships structured by state power on the other. For Fleetwood, carceral visuality refers to the state’s capacity to determine “who sees and what can be seen” and to render “incarcerated people both invisible and hyper- visible, but also unseeing and unseen” (15-16). Carceral aesthetics, however, names the forms of art-making that emerge from and across the cells, holds, and recesses of the penal landscape. They are practices of relational and affective possibility that assemble “provisional publics” or spaces of belonging, exchange, and self-making that exceed carceral divides and undermine state mandated isolation and control (21). As survival strategies, modes of critique, and methods of clandestine worldmaking, these creative practices defy the terms of obliteration and incapacitation the state demands while advancing gripping forms of aesthetic experimentation.

Carceral governance structures space, time, and matter as penal devices in a ruthless conversion of life into property; carceral aesthetics, however, mobilize them to insist on presence and to forge a visual language that rejects the state’s account of itself. What Fleetwood calls penal space, time, and matter, then, signify grounds of struggle between creation as control and creation as the “compulsion to…produce meaning under brutal and austere conditions within the larger context of the carceral state” (19). These organizing concepts orient us to prison art’s conditions of possibility, its stakes, and its terms.

Penal space refers to both locations in prisons where artists create and the “art of carceral geographies.” In San Quentin Arts in Art Studio, for example, Ronnie Goodman depicts himself in the prison studio, processing the ability to self-create as an artist while subject to surveillance as a captive, which he represents through prison blues and an observation window. Lucasville, Ohio, State Death House by Stephen Tourlentes (a nonincarcerated photographer) is a night photograph that features a residential street where several prison employees live. At the center of the piece, lights from a death-row unit illuminate the city skyline. Both Goodman and Tourlentes take up the spatiality of confinement from different locations and statuses within the carceral landscape. Penal time, Fleetwood continues, marks the temporalities of capture, from solitary confinement to parole, and “exists within centuries long practices of dispossession and captivity” (39). In Tameca Cole’s Locked in Dark Calm, we encounter a self-portrait where her face appears encased in a slab of concrete, “itself a visualization of the constraints of penal time and space and the artist’s strategies to survive them” (40). Inspired by surrealist Salvador Dali, Raymond Towler’s Passing Time features melting and dysfunctional timepieces to reflect waiting as a dynamic of psychological torment exercised by the prison system.

Penal matter, one of the most provoking conceptual offerings, refers to the materiality of incarceration including the resource constraints artists negotiate, the networks through which materials are covertly acquired and circulated, and of course the risks taken to convert contraband into works of art. Penal matter also expresses the physical experience of becoming-state-material or what Dylan Rodriguez calls the “state’s intimate bodily possession” (43). James Yaya Hough’s paintings I am the Economy and How Big House Products Make Boxer Shorts hauntingly indict this process of becoming-penal- matter. Each piece depicts a Black man’s body being fed into a machine overseen by a white guard and out of which flows dollars and boxer shorts respectively. From the machinic consumption of Black flesh comes jobs, goods, and profit. Hough’s paintings, conceived and executed from within penal space itself, not only visualize prisons as sites of commodity production, job creation, and capital accumulation but Black people as the processual means through which these are all held together in a kind of carceral supply chain: I am the economy.

Chapter 4 “Interior Subjects: Portraits by Incarcerated Artists” prompts us to think these explicit critiques of becoming-penal-matter alongside prison portraiture as another method of countervisuality. Unlike the dominant Western tradition in which portraiture memorializes lineage, status, and propertied personhood, imprisoned artists use portraiture as a “counterpose” against “state-enforced identities,” method of political alliance, relational practice to connect with non-incarcerated loved ones, and source of commissioned pay (142). Self-portraiture in particular serves as a way of locating, nurturing, and feeling a self the state attempts to disappear. Lisette Oblitas stunning In Your Eyes uses self-portraiture to process trauma and depression after she caused a car accident that led to the death of an elderly woman, Phyllis Porter. While the painting is a self-portrait, Oblitas replaces her own eyes with those of Ms. Porter, reproduced from a photo given to her by the family. She explains,

I use her eyes because it feels as though my life is no longer mine. It’s also hers. Part of her lives within me. And through her forgiveness and the family’s forgiveness, I use her eyes as a lens where I can see now with more compassion toward others.

Chapter 6 “Resisting isolation: Art in Solitary Confinement” navigates a remarkable terrain of visual work produced within spaces of living death and sensory violence: the isolation unit. “How do the restrictions on mobility, the sensory control, and the lack of human contact,” Fleetwood asks, “impact the aesthetic experiences and practices of people in solitary confinement?” (197). Connecting the proliferation of isolation units to radical movements of the 1970s, Fleetwood situates Ojure Lutalo’s political collage work within this specific context of state repression and carceral restructuring. A member of the Black Liberation Army, Lutalo was convicted of “expropriations” or what the BLA would describe as the liberation of stolen resources. He was ordered to Trenton State Prison’s Management Control Unit, specifically developed to isolate and control political dissidents.

Lutalo’s collage work, which assembles official documents, headlines, quotes, sketches, photos, and political cartoons, is a way of advancing “a pedagogy of liberation” and “maintaining a relationship with himself as a subject and witness to his life in isolation” (214). External metrics of time lose relevance and meaning within isolation and thus reflections on penal time figure prominently in his work (Lutalo was released in 2009). In response to the collage Being Prosecuted for Political Thoughts, which reads “22 YEARS IN POLITICAL ISOLATION” at the top, Fleetwood asks, “What is the duration of 22 years alone in a box?” (216) The piece also includes excerpts from a “Notice of Classification Decision” which declares,” Your radical views and ability to influence others poses a threat to the orderly operations of the Institution?” (216). “YOU CALL THIS A DEMOCRACY!” he includes next to the notice.

The state’s capacity to capture, detain, and disappear exercises itself at the dimensions most fundamental to our sensory and perceptual life. Marking Time points to the creative practices and aesthetic formations that serve as modes of critique, strategies of survival, and ways of forging aliveness in response to the explosive expansion of the penal state. Carceral aesthetics intervene on both the mandate of the prison and the mandate of museum, two Enlightenment-era institutions foundational to conceptions of freedom and personhood. This book is necessary, transformative, and will undoubtedly enliven the conceptual world and ethical range of both Carceral and Visual Studies. Borne from a “methodology rooted in practices of care and collective survival among black women [Fleetwood] learned from her entire life,” Marking Time is itself an expression of carceral aesthetics, a curatorial performance made possible through her own commitment to creating with incarcerated artists, supporting incarcerated loved ones, and “visualizing the end of human captivity” (xxii, 26).

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.